You Must Change Your Life (24 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

Her husband had been writing letters accusing her of being selfish and cruel. She insisted that she couldn't be heartless because art was itself a form of love. He begged her to come back; she begged him to let go.

Rilke had managed to avoid their conflict so far, but now he felt trapped between his two friends. He worried that if he encouraged Becker's painting too much it would look like he had chosen her side. When he left that day, Becker talked with Modersohn but remained resolved in her decision to live in Paris, writing him soon after, “Please spare both of us this time of trial. Let me go, Otto. I do not want you as my husband. I do not want it. Accept this fact. Accept this fact. Don't torture yourself any longer.”

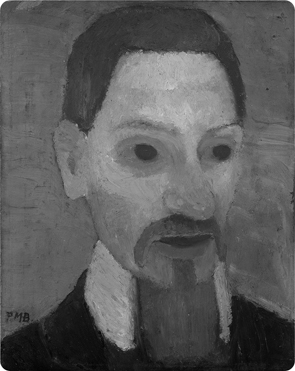

Paula Modersohn-Becker's painting of Rilke, 1906

.

Becker's sister was furious with her, while her old friend Carl Hauptmann called her ignorant and weak. Rilke did not directly weigh in either way, but he implied to her his judgment by never returning for another sitting. Becker gave up the portrait and turned instead to still lifes.

In a way, the incomplete painting is a more accurate portrait of its subject, still an outline of a man himself. Becker left the eyes as dark featureless circles, rather than filling in their pale blue color and drowsy lids. These are poet's eyes: wide open, absorbing and defenseless against their visions. The mouth stretches as “large and defined” in the painting as it does in the poem. But in Becker's image it hangs slightly open, like the freshly pruned grapevine Rilke had described. Both works are portraits of transition, but Becker's was the more prescient in its depiction of a poet on the verge.

Distancing himself from Becker, Rilke spent the next month shut up in his hotel like a monk. He would “kneel down and rise up, every day, alone in my room, and I will consider sacred what happened to me in it: even the not having come, even the disappointment, even the forsakenness,” he told his wife.

If poetry was Rilke's god, then angels were the words that would lead him to it. So it was that the stone angel from Chartres returned to him then with a verse. In “The Angel with the Sundial,” Rilke comes to terms with the distance that separates his world from the angel's. He recalls how the wind that nearly knocked him down that day had no effect on the stone sculpture. And he questions how well this angel, which holds its sundial out both day and night, understands his realm, writing in the last line, “What do you know, O stone one, of our life?”

The ideas that had been accumulating in Rilke's head over the past nine months began to pour out of him in a great exhalation that would become the first part of his two-volume

New Poems

. Although he was at least writing again, he still was penniless and lost. Not for the first time in his life, he felt like the outcast Prodigal Son.

Only now that he had been ejected from the “father's” house against his will, he saw the tale in a different light. Perhaps the prodigal's

journey into unknown territory was not selfish, but brave. Indeed, one could even pity the older son for staying. Because that boy believes that one's destiny is contingent on where one is born, his life will slog on without change. The Prodigal Son would go on adventures, taste freedom and maybe even find god.

This was the kind of Prodigal Son Rodin had depicted with his bronze boy kneeling on the ground, his arms flung toward the sky. The work was originally titled

The Prodigal Son

, and later changed to

Prayer

, but Rilke recognized neither title as correct, writing in the monograph, “This is no figure of a son kneeling to his father. This attitude makes a God necessary, and in the figure thus kneeling are present all who need Him. All space belongs to this marble; it is alone in the world.”

Rilke subverted the parable this way in his poem “The Departure of the Prodigal Son,” which begins:

Yes, to go forth, hand pulling away from hand.

Go forth to what? To uncertainty,

to a country with no connections to us

He then uses the poem's last lines to applaud the son's exit, rather than his return:

To let goâ

even if you have to die alone.

Is this the start of a new life?

For Rilke, it was at least the start of a new chapter. He had officially left the house of Rodin and, by the end of July, would move on again, first briefly to the coast of Belgium and then to Berlin. His patron Karl von der Heydt had sent him two thousand marks to help support him during these uncertain times. “This last period has been confused, the

leave-taking from Paris difficult and inwardly complicated,” Rilke had told him. In September the poet set his sights on Greece and made an elaborate appeal to von der Heydt to fund the trip as well. He told him that he needed to complete the second essay on Rodin, and could think of no better setting for this work than Greece, the sculptor's spiritual homeland.

But then those plans evaporated when a baroness invited Rilke to be her guest in Capri for the winter. By then, von der Heydt's patience had started wearing thin. He scolded Rilke for his neediness, arguing that a poet might require financial support in the beginning, but should ultimately strive for financial independence.

Rilke replied to the accusation with predictably tangled logic, claiming that it was

because

he placed such a premium on independence that he had not been able to support himself. Rodin's employment had imprisoned him at the expense of his work for too long and he refused to relinquish that freedom again for a job.

In the end von der Heydt sent the money and off Rilke went, arriving in Capri on his thirty-first birthday.

RILKE'S PATRON WAS NOT

the only person becoming frustrated by the poet's capricious and costly travels. Back in Berlin, Westhoff complained to her new friend Andreas-Salomé about Rilke's prolonged absences. Their so-called “interior marriage,” based on letters and distance, had left her to raise Ruth alone, and she often barely scraped by on her teaching income.

Andreas-Salomé was horrified. She advised Westhoff to notify the police if Rilke did not begin fulfilling his paternal obligations soon. Westhoff must have known that the mere suggestion of legal actionâparticularly coming from his dear Louâwould humiliate Rilke, hopefully into compliance. She wrote to her husband to tell him what his friend had said.

As she expected, the letter detonated on Rilke's Italian vacation. He wrote an impassioned defense to his wife and, in a roundabout way, to

Andreas-Salomé, whom he knew would hear about it. He accused his old friend of hypocrisy, reminding them how Andreas-Salomé had always urged him to elevate his art above all external demands. Being a father was an honorable pursuit, but a poet's calling was an imperative, he said, ignoring the fact that Andreas-Salomé's actual advice was to not start a family at all.

Rilke pleaded with his wife for understanding and then he praised her. But he stuck to his resolve to pursue the prodigal path: “I will not give up my hazardous, so often irresponsible position and exchange it for a more explainable, more resigned post until the last, the ultimate, final voice has spoken to me,” he said.

It's not that Rilke didn't value love, he just preferred it as an intransitive verb: without object, like a radiating circle. Otherwise to love was to possess another, while to be loved was to be possessed. Or, as he would more pointedly put it in

Malte

, “To be loved means to be consumed in flames. To love is to give light with inexhaustible oil. To be loved is to pass away; to love is to endure.” To Rilke, the home's hearth was the brightest-blazing fire and he would rather jump out a window than risk burning alive; if he fell flat, at least a scarred face was better than one that resembled somebody else's. To Rilke, family was the ultimate annihilation of self.

He failed to see that his wife at least partly agreedâexcept that it was she who wanted to fulfill

her

calling. So while Rilke spent his Christmas in Capri, Westhoff made her way to Egypt, where some friends had offered her a few commissions and a place to stay while she worked. Rilke had not seen her so determined in years: “Since that first contact with Rodin she has not reached out for anything with so much need and real hunger as now.”

As he entered a fallow period in his own career, he was perhaps a bit envious of her industriousness, too. His trip to Italy had proved to be an utter mistake. There were too many distractions there: drunken German tourists thundered through town, while his hostess's friends did too much socializing and too little work. Although one could always locate remote corners in Italy to find peace, Paris was the only place where he had truly been able to work. The city had treated him

a bit like military school, forcing him to overcome his fears by writing through them. Except this time Rodin drove him out before he had the chance to complete his education.

“I have again stored up so very much longing for complete solitude, for solitude in Paris. How right I was when I considered that the next necessity, and how much harm I did myself when, contrary to all understanding, I half missed, half wasted this opportunity. Will it come again? On that, it seems to me, everything depends,” he wrote in February.

He bided his time until spring, when Westhoff returned from Egypt. They spent two weeks together in Italy, but any lingering trace of passion between them was now permanently gone. Rilke had been eager to hear her tales from Africa but she came back with nothing to say. She walked around with a look of disappointment on her face that reminded him of Beuret, whose perpetually grimaced look made one acquaintance exclaim, “My god, was it really necessary for her to make herself look so unloved?” Then Westhoff and Rilke's paths diverged once again; this time she left for Germany and he went to France, alone. Although the pair maintained a close bond for years to come, the image of their marriage was one they no longer tried to frame.

Rilke knew Paris would be different this time around. He was nobody's son now, nobody's secretary. He was scarcely even a father or husband anymore. Let lovers consume each other like wine, he reasoned, he had finally disentangled himself from those vines. When Franz Kappus once complained that the loved ones in his life were going away, Rilke told him that he should instead see how “the space around you is beginning to grow vast.” This was the empty place where he found himself now, somewhere between the lines, where he could breathe free at last.

CHAPTER

11

A

S THE TWENTIETH CENTURY TORE OFF FROM THE NINETEENTH

, a new generation of artists ventured into unknown territory without looking back. In Western Europe, many embraced the colonial spirit of exploration in their work by appropriating “primitive” African art and toying with sexual taboos. In a few short years, the cottony brushstrokes of Impressionism had hardened into the spiky lines of Cubism, and Monet's parasol-adorned ladies had stripped down to Toulouse-Lautrec's feathers and garters.

Simultaneous strides toward Cubism in France, Futurism in Italy and Expressionism in Germany all paved the way for a new abstract art, which promised to either liberate painting or destroy it, depending on whom you asked. If there was such a thing as a literary manifesto for the moment, it was the German art historian Wilhelm Worringer's 1908 book

Abstraction and Empathy: A Psychology of Style

.

The work was originally intended solely as a dissertation, and the twenty-six-year-old doctoral candidate never anticipated the widespread enthusiasm that greeted the text upon its publication. The idea for the book had come to him by chance. As he explained in a foreword to a later edition, he had been searching long and aimlessly for

a research topic when it hit him one day in 1905, during a visit to the Trocadéro, Paris's museum of ethnographic art.

Many Parisians avoided the musty, run-down building, which was a relic from the 1878 World's Fair. There was no one else there that spring day, apart from Worringer and two older gentlemen, he later recalled. Then he recognized one of them as none other than Georg Simmel, his former professor in Berlin. The sociologist was in Paris for the meeting with Rodin that Rilke had helped arrange for him.