World War One: History in an Hour (3 page)

Read World War One: History in an Hour Online

Authors: Rupert Colley

Tags: #History, #Romance, #Classics, #War, #Historical

In October 1914, Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) entered the war on the side of the Central Powers and on Christmas Day went on the offensive against the Russians, launching an attack through the Caucasus. The Tsar sent an appeal to Britain, asking for a diversionary attack that would ease the pressure on Russia. In the event, the Turks failed miserably in its first campaign in Russia, losing 70 per cent, dead or wounded, of an army estimated to be at least 100,000 strong. Enver Pasha blamed Turkey’s defeat on Armenian deserters who had gone over to the Russian side. Retribution was brutal, resulting in the Armenian massacre, sometimes considered the first genocide, in which Armenians were deported to Syria. Famine, disease and murder resulted in one to two million Armenian deaths.

The British pressed on with its plan for a diversionary attack, to use the Royal Navy to take control of the Dardanelles Straits from where they could attack Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. The Dardanelles, a strait of water separating mainland Turkey and the Gallipoli peninsula, is 60 miles long and, at its widest, only 3.5 miles. Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, insisted that the Royal Navy, acting alone, could succeed. On 19 February, a flotilla of British and French ships pounded the outer forts of the Dardanelles and a month later attempted to penetrate the strait. It failed, losing six ships, half its fleet. Soldiers, it was decided, would be needed after all.

Lord Kitchener placed in charge Sir Ian Hamilton, but sent him into battle with out-of-date maps, inaccurate information and inexperienced troops. A force of British, French and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corp) troops landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April. The Turks were waiting for them in the hills above the beaches and unleashed a volley of fire that kept the Allied troops pinned down on the sand. As on the Western Front, stalemate ensued. The Allies, under constant attack, took cover as best as they could among the rocks, with only the beach behind them and, without shade, exposed to searing sun. Their fallen comrades lay putrefied and bloated beside them, the stench filling the air.

Australian artillery during the Gallipoli Campaign, 1915

On 6 August, the British launched a renewed attack. The ANZACs would attempt to break out from their beach and take the high ground whilst a British contingent of 20,000 new troops led by General Sir Frederick Stopford would land on Sulva Bay on the north side of Gallipoli. Stopford’s men made a successful landing, outnumbering the enemy by fifteen to one. Instead of pressing home their advantage, the general gave his men the afternoon off to enjoy the sun while he had a snooze. Hamilton advised but did not order an advance. By the time Stopford did advance, it was too late, the Turks had rushed men into position and the stalemate of before prevailed.

The Allied troops endured further months of misery. 70 per cent of the ANZACs suffered from dysentery, where medical care, unlike the Western Front, was at best primitive. With the onset of winter, the troops, without shelter and exposed to the elements, suffered frostbite. Kitchener was dispatched by the British government to check on the situation. Appalled, he returned to London and urged evacuation. Finally, in January 1916, the curtain fell on the whole sorry ‘side show’. A contrite Churchill resigned and punished himself by joining a company of Royal Scot Fusiliers on the Western Front. He returned to politics a year later and in 1917 was appointed Minister of Munitions. Meanwhile, Kitchener, who had been progressively side-lined, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Russia. On 5 June 1916, his ship, the HMS

Hampshire

, hit a German mine off the Orkney Islands and sunk. His body was never found.

During 1915, Germany dangled a bait in front of neutral Bulgaria – help us defeat Serbia and we’ll give you Macedonia, territory Bulgaria lost to Serbia after the Balkan War of 1912–13. Unable to resist, the Bulgarian king, the German-born ‘Foxy Ferdinand’, Ferdinand I, entered the war in October 1915 and immediately joined the German–Austrian assault on Serbia.

Twice, in 1914, the Austrian–Hungarian’s ventures in Serbia had met with defeat. Not this time. In October 1915, the Allies, attempting to aid Serbia, sent a force to the Greek port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki) from where it was only fifty miles to the landlocked Serbia. Too late. Heavily outnumbered, Belgrade fell and the Serbian army was forced into a desperate retreat over the mountains of Albania, struggling in the snow alongside thousands of Serbian refugees. Starvation, cold and disease decimated their number, both soldier and civilian alike. Eventually, the remnants arrived at the Adriatic coast, where they were rescued by the Allies and evacuated to Corfu. Austria–Hungary had avenged the death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Serbia had paid for it by losing one-sixth of her whole population.

The Allied troops in Salonika however stayed put to dissuade the Greeks from joining the German cause (after all, they reckoned, the Greek king was married to the Kaiser’s sister). And there the Allied troops remained for the rest of the war, half a million men, mocked as the ‘the Gardeners of Salonika’, whose services could have been better used elsewhere. Greece eventually joined the war on the side of the Allies in July 1917.

In November 1914, the British sent a force to protect the Suez Canal in Egypt from Turkish troops based in Turkish-controlled Palestine. In late-January and February 1915, as expected, the Turks tried to seize the canal and again in July 1916, but both assaults were easily repulsed.

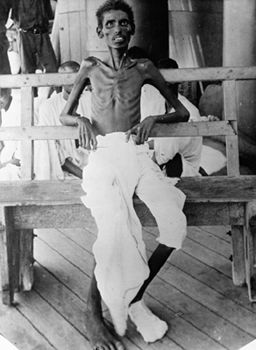

Another British force, consisting mainly of Indian troops, occupied Basra in Turkish-Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in November 1914 to secure its oil wells. From there, with a hold on Turkish territory, it made sense to extend its gains and capture Baghdad, which would, according to Asquith, ‘maintain the authority of our flag in the East’. In August 1915, a force led by General Charles Townsend pushed forward under 43° C heat and, along the way, occupied the town of Kut-el-Amara. Urged to advance onto Baghdad, Townsend did but, meeting a determined Turkish counter-attack, was forced back to Kut where his men came under siege. With supplies running low and the situation desperate, attempts were made to rescue Townsend but these failed, with a loss of 23,000 lives. After 147 days of siege, starving and unable to hold out, Townsend surrendered on 29 April 1916. His 13,000 men, one third of whom were Indian, were marched off to captivity, where up to 70 per cent were to die of malnutrition.

Indian soldier shortly after the Siege of Kut, 1916

In December 1916, the British, under General Stanley Maude, made a fresh attempt to capture Baghdad. Maude recaptured Kut and on 11 March 1917, beat the Turks out of Baghdad. ‘Our armies,’ proclaimed Maude to the citizens of Baghdad, ‘do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.’

In January 1917, British troops marched towards Jerusalem, determined to oust Turkey from Palestine. Along the way, the British tried twice to take Gaza and twice failed. The third attempt, in November, led by General Sir Edmund Allenby, was successful, leading to the capture of Jerusalem on 11 December 1917. In January 1916, in a secret agreement known as the Sykes–Picot Agreement (after its authors), the British and French agreed the partition of Palestine and Mesopotamia, at that point still under the rule of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. At the same time, the British were offering bits of Turkey to the Russians, Italians, and the Arabs. The Arabs, accordingly, played their part in the British campaign. Led by the enigmatic T. E. Lawrence, they continuously disrupted Turkish communications through sabotage and guerrilla tactics. On realizing the British had conflicting plans for Palestine, the Arabs felt betrayed, even more so with the Balfour Declaration of November 1917. Britain’s foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, proposed a permanent settlement for Jews within Palestine. The stipulation that ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’ did nothing to allay Arab concerns.

In Germany, Falkenhayn decided that Germany’s ‘arch enemy’ was not France, but Britain. But to destroy Britain’s will, Germany had first to defeat France. In a ‘Christmas memorandum’ to the Kaiser, Falkenhayn proposed an offensive that would compel the French to ‘throw in every man they have. If they do so,’ he continued, ‘the forces of France will bleed to death’. The place to do this, Falkenhayn declared, would be Verdun.

An ancient town, Verdun was surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, symbolically significant to the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joffre was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit to Joffre, waking him from his slumber and insisting that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat but everyone else will.’

Sent by Joffre, Henri-Philippe Pétain organized a stern defence of the city and managed to protect the only road open to the French. Every day, while under continuous fire, 2,000 lorries made a return trip along the 45-mile

Voie Sacrée

(‘Sacred Way’) bringing in vital supplies and reinforcements to be fed into the furnace that had become Verdun. Serving under Pétain was General Robert Nivelle who famously promised that ‘

on ne passe pas

’ (they shall not pass), a quote often attributed to Pétain. Joffre demanded that Haig open up the new offensive on the Somme to take the pressure of his beleaguered men at Verdun. Haig, concerned that the new recruits to the British army were not yet battle-ready, offered 15 August as a start date. Joffre responded angrily that the French army would ‘cease to exist’ by then. Haig brought forward the offer to 1 July.

German infantry advancing during the Battle of Verdun, 1916

During June, the attack and counter-attack at Verdun continued. On the Eastern Front, the Russian general, Aleksei Brusilov, attacked the Austrians, who in turn, appealed to Falkenhayn for help. Falkenhayn responded by calling a temporary halt at Verdun and transferring men east. The Battle of Verdun wound down, then fizzled out entirely. The French, under the stewardship of Nivelle regained much of what they had lost. After ten months of fighting, the city had been flattened, and the Germans and French, between them, had lost 260,000 men – one death for every ninety seconds of the battle.

The Russians, in what became known as the Brusilov Offensive, shattered the Austrian army to an extent it never fully recovered. With Falkenhayn’s Germans coming, Brusilov called for reinforcements of his own – but none came. Brusilov’s success against the Austrians was countered by his defeat to the Germans.