World War One: A Short History

Read World War One: A Short History Online

Authors: Norman Stone

Tags: #World War I, #Military, #History, #World War; 1914-1918, #General

World War One

NORMAN STONE

World War One

A Short History

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa)(Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published 2007

1

Copyright © Norman Stone, 2007

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by

any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner

and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

EISBN: 978–0–141–04095–0

Contents

List of Illustrations

Photographic acknowledgements are given in parentheses

Outbreak

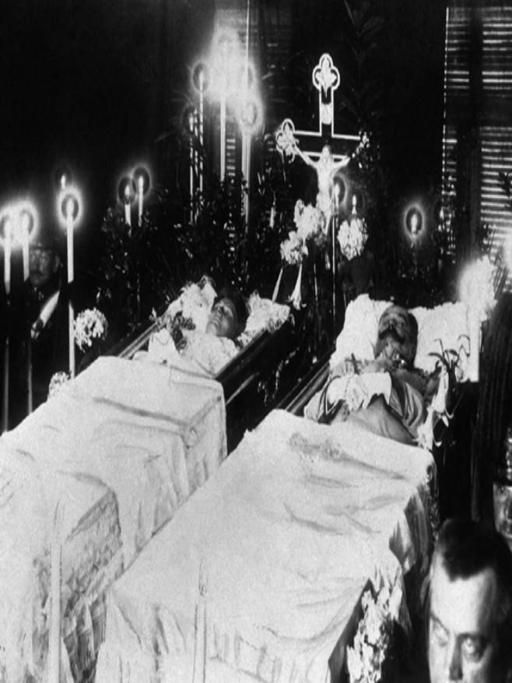

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie lying in state (Hulton-Deutsch

Collection/Corbis)

1914

Calling up of Turkish troops in Constantinople

(Bettmann/Corbis)

1915

French 220 cannon on the Western Front

(Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

1916

British gasmasked machine-gun unit on the Somme

(Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

1917

Russian troops in eastern Galicia running past a church during unidentified battle

(Bettmann/Corbis)

1918

British Mark IV tank

(Corbis)

Aftermath

Returning German army marching through Berlin

(Stapleton Collection/Corbis)

List of Maps

3. The Eastern Front, 1914–1918

4. The Balkans and the Straits

5. The Western Front, 1915–1917

6. The Italian Front, 1915–1918

Introduction

In 1900, the West, or, more accurately, the North-West, appeared to have all the trumps, to have discovered some end-of-history formula. It produced one technological marvel after another, and the generation of the 1850s – which accounted for most of the generals of the First World War – experienced the greatest ‘quantum leap’ in all history, starting out with horses and carts and ending, around 1900, with telephones, aircraft, motor-cars. Other civilizations had reached a dead end, and much of the world had been taken over by empires of the West. China, the most ancient of all, was disintegrating, and in British India, the Viceroy, Lord Curzon, not a stupid man, was proclaiming in 1904 that the British should govern as if they were going to be there ‘for ever’.

The title of a famous German book is

War of Illusions

, and the imperial illusion was only one of them. Within ten years much of the British empire was turning into millions of acres of bankrupt real estate, partly ungovernable and partly not worth governing. Thirty years on, and both India and Palestine were abandoned.

The governments that went to war all made out that they were acting for national defence. But it was empire that they had in mind. In 1914, the last of the great non-European empires was disintegrating – Ottoman Turkey, which, in (very theoretical) theory, stretched from Morocco on the Atlantic

coast of Africa through Egypt and Arabia to the Caucasus. Even then, oil had become important: the British Navy went over to it, as against coal, in 1912. The Balkans mattered because they were quite literally in the way, on the road to Constantinople (as even the Ottomans called it at the time:

Konstantiniye

). As it happens, I have written this book partly in a room with a view over the entire Bosphorus, through which a huge volume of traffic, from oil-tankers to trawlers, flows every day and night. It is the windpipe of Eurasia, as it was in 1914.

It is ironic that the only long-lasting creation of the post-war peace treaties, Ireland perhaps excepted, has been modern Turkey. In 1919, the Powers tried to partition her, partly using local allies, such as the Greeks or the Armenians. In a considerable epic, to the surprise of many, the Turks fought back and in 1923 re-established their independence. The process of modernization – ‘westernization’, it has to be called – has not been straightforward, but it has been remarkable just the same. Chance – a conference on the Balkans – brought me there in 1995, and I stayed. I should like to acknowledge the support that I have had from Professor Ali Dogramaci, Rector of Bilkent University. It has been the first private university in what might be called ‘the European space’, and the success of its example is shown in the widespread imitation that has followed. I have encountered a great deal of kindness in Turkey, and can easily see what old von der Goltz Pasha, the senior German officer involved in the First World War, was driving at when he wrote, of his two-decade-long experiences, that ‘I have found a new horizon, and every day I learn something new.’ Through Professor Dogramaci, an expression of collective gratitude.

Some friends and colleagues deserve separate mention just the same. Professors Ali Karaosmanoglu and Duygu Sezer were very helpful from the first day, and I should also like to

acknowledge the help I have had especially from Ayse Artun, Hasan Ali Karasar, Sean McMeekin, Sergey Podbolotov in matters Turco-Russian, and Evgenia and Hasan Ünal, who introduced me to the history of the Levant. Rupert Stone, my target reader, read the manuscript and made suitable comments. My assistants, Cagri Kaya and Baran Turkmen, also a target readership, have kept the administrative show on the road, learned their Russian, and taught me how to manage writing machines.

A NOTE ON PROPER NAMES

Author and reader alike have more important concerns, in the First World War, than strict consistency over place names that have frequently changed. I have tended to use the historic ones, where they are not fossils: ‘Caporetto’ makes more sense than the modern (Slovene)‘Kobarid’, whereas ‘Constantinople’ is now obsolete. I have generally shortened ‘Austria-Hungary’ to ‘Austria’. It is impossible to get these things right; may convenience rule.

World War One

ONE •

OUTBREAK

preceding pages: Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie lying in state

The first diplomatic treaty ever to be filmed was signed in the White Russian city of Brest-Litovsk in the early hours of 9 February 1918. The negotiations leading up to it had been surreal. On the one side, in the hall of a grand house that had once been a Russian officers’ club, sat the representatives of Germany and her allies – Prince Leopold of Bavaria, son-in-law of the Austrian emperor, in field marshal’s uniform, Central European aristocrats, leaning back patronizingly in black tie, a Turkish Pasha, a Bulgarian colonel. On the other were representatives of a new state, soon to be called the Russian Socialist Federation of Soviet Republics – some Jewish intellectuals, but various others, including a Madame Bitsenko who had recently been released from a Siberian prison for assassinating a governor-general, a ‘delegate of the peasantry’ who had been picked up from the street in the Russian capital at the last minute as useful furniture (he, understandably, drank), and various Russians of the old order, an admiral and some staff officers, who had been brought along because they knew about the technicalities of ending a war and evacuating a front line (one was an expert in black humour, and kept a diary). There they are, all striking poses for the cameras. It was peace at last. The First World War had been proceeding for nearly four years, causing millions of casualties and destroying a European civilization that had, before war broke out in 1914, been the

proudest creation of the world. The war had destroyed Tsarist Russia; the Bolsheviks had staged their revolutionary take-over in November 1917; they had promised peace; and now at Brest-Litovsk they got it – at German dictation.

The terms of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk were quite clever. The Germans did not take much territory. What they did was to say that the peoples of western Russia and the Caucasus were now free to declare independence. The result was borders strikingly similar to those of today. The Baltic states (including Finland) came into shadowy existence, and so did the Caucasus states. The greatest such case, stretching from Central Europe almost to the Volga, was the Ukraine, with a population of 40 million and three quarters of the coal and iron of the Russian empire, and it was with her representatives (graduate students in shapeless suits, plus an opportunistic banker or two, who did not speak Ukrainian and who, as Flaubert remarked of the type, would have paid to be bought) that the Germans signed the filmed treaty on 9 February (the treaty with the Bolsheviks followed, on 3 March). With the Ukraine, Russia is a USA; without, she is a Canada – mostly snow. These various Brest-Litovsk states would re-emerge when the Soviet Union collapsed. In 1918, they were German satellites – a Duke of Urach becoming ‘Grand Prince Mindaugas II’ of Lithuania, a Prince of Hesse being groomed for Finland. Nowadays, Germany has the most important role in them all, but there is a vast difference: back then, she was aiming at a world empire, but now, in alliance with the West, she offers no such aims – quite the contrary: the difficulty is to get her to take her part confidently in world affairs. The common language is now English, and not the German that, in 1918, everyone had to speak as a matter of course. Modern Europe is Brest-Litovsk with a human face, though it took a Second World War and an Anglo-American occupation of Germany for us to get there.