Work Clean (16 page)

Authors: Dan Charnas

A chef's reprise: No shortcuts

By the time Eden opened his first restaurant, Shorty's 32, the idea of making first moves had become instinctiveâas it remains for him now at the reincarnation of August on Manhattan's Upper East Side.

An order comes inâ

bam!

âEden's hand slaps a pan onto the stove by reflex. He doesn't think, doesn't realize it's happening. Every 2 seconds now saves him a minute later. Every pan down is the first move in a series of moves that need to happen to complete a dish. Without the first move, none of the other moves can happen. Eden tries to make as many first moves as he can. When he goes down to the storeroom, he returns with armfuls of ingredients and tools he knows he'll need for his mise-en-place, that he knows his other cooks will need. The newer members of the kitchen look at their chef like he's crazy.

But Eden knows:

Do it now, don't wait for later. Now I'm calm and steady and energetic; later I'm stressed and jittery and exhausted. Now I'm moving perfectly, which saves me time; later I'm making mistakes, which cost me time. One easy shortcut now can force me into any number of bad shortcuts later.

In service Eden urges his cooks to make the first moves, as his chef reminded him to do, and as his chef's chef didâ

Guys . . . pans down!â

a lesson about time handed down through time.

Recipe for Success

Commit to using time to your benefit. Start now.

FINISHING ACTIONS

A chef's story: The delivery woman

Chef Charlene Johnson-Hadley was buried in mushrooms, eight cases in all. Hundreds upon hundreds of musky expressions of earth covered every available work surface around her. Charlene needed to examine and sort each of them, tossing the unusable ones and arranging the rest on sheet trays. Then she'd have to plunge batches of them into cold water, removing loose soil, twigs, and other impuritiesâanother painstaking task. After that, they'd need to be sliced and roasted. The mountain of mushrooms would reduce to almost nothingâcaramelizing, crisping, sweetening, losing their water and most of their massâending up as tasty slices in the mushroom soup devoured by the lunch guests at Chef Johnson-Hadley's restaurant, American Table in New York City.

Charlene couldn't focus. Her mind leapt to the other projects she needed to accomplish that day. There was a pecan tart. There were sherbets to make. A couple of times Charlene caught herself walking away from her station to start something elseâthe act was completely involuntaryâbut turned herself around before she got too far.

“Stop, Charlene,” the chef said aloud. “No, you need to finish sorting these . . . ”

Those mushrooms.

Her subconscious was doing anything it could to get her away from them. She talked herself through the task, like her chef would have talked her through it, like her mother would have.

When the younger Charlene Johnson announced to her mother Hyacinthâa Jamaican immigrant with a master's in educationâthat she didn't want to finish college, she worried. After the death of a grandmother with whom she was particularly close, Charlene's pursuit of a psychology degree had left her feeling increasingly empty. She told Hyacinth that she wanted to leave academia and learn how to make pastry, and braced for the worst. Instead, her mother gave Charlene her best: “Why limit yourself? Get a culinary degree. That way, you'll get cooking as well as baking.”

After attending the French Culinary Institute, Charlene moved through jobs of escalating responsibility: working with Francois Payard at his famous bistro and patisserie on New York's Upper East Side, rising from line cook to sous-chef at designer Nicole Farhi's restaurant, and taking the top chef's job at Farhi's 202 Cafe in Chelsea. But in late 2010, she saw that the former chef of Aquavit, Marcus Samuelsson, was opening a new upscale, concept restaurant in Harlemâa neighborhood whose most famous culinary attraction until that point had been the down-home soul food restaurant Sylvia's. Samuelsson, an Ethiopian raised in Sweden by adoptive parents, climbed out of some of the best kitchens of Europe into New York City. He was now making an equally improbable leap on behalf of his adopted locale: to bring fine dining uptown in a way that honored Harlem's particular cultural and racial legacy. Charlene got herself an interview and a chance to “trail” in the kitchen, meaning she could observe and have the chefs observe her, too. She had never seen so many chefs of color in a high-end kitchen. Even though she was already a full-fledged chef, she took a line cook job at the new restaurant just to be a part of Samuelsson's enterprise. He named it Red Rooster, after a speakeasy from Harlem's Renaissance period in the early 20th century.

Through the opening in 2011 and beyond, Samuelsson watched Charlene and came to know her as calm, dependable, and disciplined. One evening in the winter of 2012, about a year after she began working at Red Rooster, she felt a hand on her arm. It was Chef.

“Come with me,” Samuelsson ordered.

Oh God, what did I do?

Charlene wondered.

In a secluded corner of the kitchen Samuelsson told her, “I want you to know that I've noticed all of your work. I've got some things happening this year, and I want you to be a part of it. I just want you to prepare yourself.”

Samuelsson made Charlene the executive chef of his restaurant in the sleek new home of the Juilliard School at Lincoln Center. The name itself was a mouthful: American Table Cafe and Bar by Marcus Samuelsson. And that job came with a catch: The kitchen was located in another building across the street, and finished food would have to be carted back and reheated for service. The operation would call on all of Charlene Johnson-Hadley's mental and physical mise-en-place.

After the opening, one food critic visited twice and enjoyed his meals before discovering that American Table was a restaurant without a kitchen on premises, a feat that he credited to “the menu created by Samuelsson and his fellow Swede-in-crime Nils Norén.”

Meanwhile, in the bowels of Lincoln Center, the uncredited chef Charlene Johnson-Hadley ran the engine that made American Table go. Being chef today meant clawing her way out of this pile of mushrooms. She couldn't do it if she didn't stand still and deliver.

A half-hour later she was still coaching herself: “Yes, now we need to plunge these.”

Even after years in the business honing her discipline, she found this was the hardest part of the gig, but one of the most crucial: maintaining a finishing mentality. It was too easy to give in to fatigue and frustration. It was too easy to stop or pause a project as the finish line came into view with a deluded confidence that it could be completed later. She knew that if she indulged her restlessnessâeven with the intention to get another project startedâshe would end up throwing her entire day off. If she didn't start the mushrooms, complete them; start the short ribs, complete them; start the pecan tarts, complete them; none of them would have gotten done. Charlene Johnson-Hadley respected the iron law of the kitchen: A dish that is 90 percent finished has the same worth as a dish that is zero percent finished.

Chefs deliver

Just as chefs have a philosophy about starting, they have a doctrine of finishing that springs from the distinctive character of their work.

The very nature of the kitchen's product demands that chefs develop a finishing mentality. Dishes, for the most part, are all-or-nothing. A chef cannot serve a steak au poivre without the peppercorn sauce, at least not if she expects to keep customers who know the difference. A menu cannot promise fries on the side and fail to deliver them. And let's presume, just for the sake of argument, that the customer isn't so discerning. The customer can't be served at

all

unless the cook puts a plate in the pass. A bunch of dishes in various stages of completion are useless until at least one of them is finished. Ninety percent done is still zero percent done from the perspective of the customer. So a cook must develop a delivery mind-set.

The finishing imperative comes from the nature of kitchen production

â

churning out massive quantities of high-quality food. Finishing all that food requires a lot of repeated motion. The economy of repeated motion is the principle on which the industrial assembly line is built. Individual workers can get more work accomplished, and faster, if they do the

same

action or job repeatedly. If a worker stops, the whole line stops. We can measure the cost of the stoppage not only in minutes lost during a pause, but also in minutes spent ramping up production again. Think of someone like Chef Johnson-Hadley as an assembly line unto herself. She has a number of jobs to do. But she knows she will be more efficient if she does

one

job at a timeâto

aggregate alike actions

âthan if she stops and does something else, skipping from one action to another. Momentum and aggregation are key rationales for continuing with an action until it is done.

Aside from the goal of delivering the product, the virtues of finishing are twofold.

In the physical realm, finishing yields precious space. Most cooks work in tight spaces, and their workstations must move through several phases of mise-en-place throughout the day: prep, cooking, service. A clean and efficient service is impossible when your station is still covered with the remains of bulk prep work. Finishing those actions conserves space and clears space for the next actions.

Finishing actions clears the mind as much as it clears the plate. An action once finished does not need attention or memory. An unfinished action still needs both to be completed. An accumulation of unfinished actions creates a mental clutter and a brain drain. Whether we possess the kind of mind that deals with that clutter easily or not, the cataloguing and prioritization of those remaining actions demands mental energy that could be spent elsewhere.

Jarobi White recalls cutting carrots in Josh Eden's kitchen at August, placing them in a container, and sealing the lid.

Done

.

Not done,

said Chef Eden.

The container isn't labeled. It's still on your cutting board. It's not in the refrigerator. It's still on your metaphorical plate. Clean your plate.

“I say it all the time: You start a job and you finish a job,” says Eden.

Chefs say two seemingly contradictory things. On one hand, they counsel the importance of making first moves immediately. On the other, they loathe the incomplete:

Don't start what you can't finish.

But how can we start

and

finish everything? We can't. Chefs are saying something more subtle: “Starting” is less about doing

everything

immediately and more about creating a triage system to pri

oritize current and future actions. “Finishing” is not so much about completing

everything

and more about not being distracted by the periodic “starting” of other things. “Finishing” can also be stopping a project while it's incomplete but taking just an extra few seconds to wrap it up for resumption later so as to not leave loose ends hanging. What chefs attempt to avoid are

orphaned tasks

âthings that take up physical and mental space because they haven't been tied up in the easiest possible form to be resumed later. And since the polarities of starting and finishing generate tension between them, we must always begin with the end in mind. When you start a project, ask one question:

How and when will I finish?

Chef Eden has seen the consequences of failing to account for finishing when starting: “You're stuck in a kitchen 2 hours past the time you were supposed to go home because you've started 16 projects and you haven't finished one of them. And then you can't leave. Or you're throwing it all in the garbage.”

The principle of finishing actions asks us to

work clean

with obligations and expectations, those that others set for us and those we hold for ourselves.

Finishing actions might not seem so important to those of us who work primarily with words, numbers, images, and people rather than perishables. If I don't finish an e-mail, I don't have to trash it. A half-drafted memo doesn't “go bad.” But it occupies space on my physical or virtual desktop. It preoccupies my mind now, and later when I remember it's not finished. And it can slip my mind until someone or something reminds me that I'm late, that I've failed a commitment.

Better to confront the reasons why we stop before finishing and learn mental and physical techniques to push through.

Better to enjoy the temporal, physical, and mental dividends of finishing than pay the price later for not doing so.

Better to not open too many projects at a time so that I keep orphaned tasks to a minimum and give myself a fighting chance at finishing them.

And better to deal with the incomplete by finding a way to tie it up, temporarily, so that it doesn't crowd precious physical and mental space.

Says chef-author Michael Gibney: “Every time you cross something off of your list, you get a little endorphin rush. Every time you deliver, you get that thing out of your life.”

The perishable and holistic nature of kitchen products and the limited time frame and repetition of kitchen production yield a culture of finishing like no other. We can integrate the principle of finishing actions into our own lives by applying ourselves to the following strategies.

Excellence is quality delivered.

DEVELOPING A NOSE FOR THE FINISHABLE

Conscious finishing begins with conscious starting. Our chances of success grow when we ask ourselves “What's finishable?” at the start.

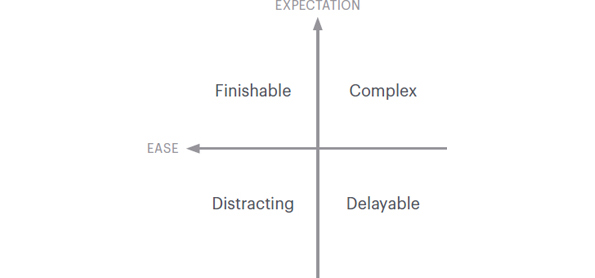

We judge the finishable by two parameters:

ease

and

expectation.

Ease

is time plus energy: How quickly can we finish something, modulated by how much or how little energy we expend in that time?

Expectation

is deadline plus stakeholders: Who is waiting for our product, and when do they expect it?

â

High-expectation and high-ease tasks are

finishable.

â

Low-expectation and low-ease tasks are

delayable.

â

Low-expectation and high-ease tasks are

distracting.

â

And high-expectation and low-ease tasks are the

complex

tasks that most need scheduling.

When you put these together, they form a different version of the Eisenhower Matrix.

Now remember our principle of “hands-on” immersive time and “hands-off” process time? We can complete immersive tasks on our own; process tasks require us to interact with physical

processes or other people to get benefit. Thus process tasks usually have higher expectation and, because they often take less time and thought, are easier to execute. They tend to be more “energy efficient” or productive than immersive tasks because the work that we unlock from them is actually done partly by others. Process tasks are among the “low-hanging fruit” that we should look to pick when conducting a triage for tasks to start or to finish. They compete, however, with immersive tasks that are lower in ease and expectation but higher in long-term benefit. In other words, there are beneficial things we must do that aren't easy and finishable, and those must be weighed alongside the easily finishable. The key in conscious starting is to cultivate a balance between the finishable tasks (high expectation/high ease) and the complex tasks (high expectation/low ease). This balance is the recipe for survival in the contemporary workplace.

What would a day look like that had this balance? Let's examine the “to-do” list of Sheila, a schoolteacher. Sheila has 4 hours in which to do some combination of the tasks below.

â

Lesson plan for tomorrow (3 hours)

â

Student assessments, half-finished, due last week (2 hours)

â

Class trip forms due tomorrow (30 minutes)

â

Compose e-mail for parent-teacher meetings to send later in week (1 hour)

â

Go to bookstore to buy book for next semester (1 hour)

What actions should Sheila choose?

The tasks with the greatest ease (measured by

time

) are the class trip forms, the e-mail for parent-teacher meetings, and the bookstore errand.

The most expected tasks (measured by

deadline

) are the lesson plan, class trip forms, and the student assessments.

So the most finishable task (high ease/high expectation) is the class trip forms.

The most complex (low ease/high expectation) are the lesson plan and the student assessments.

Sheila can't do

both

complex tasks, so she has to choose one of them. Because she cultivates a delivery mentality, she considers both the political and practical repercussions of her decisions. On the political side, she decides that since she's already late on the assessments,

staying

late would be preferable to delivering them but then being late on a

new

piece of work (lesson plan), thereby reinforcing a track record of late work with her colleagues and superiors. On the practical side, she doesn't want to trade being prepared in the classroom tomorrow for delivering something that's already late. So she decides to deliver on the most finishable task (the class trip forms) and the more complex project (the lesson plan), for 3.5 hours of work. After slam-dunking those two, she will spend the last half-hour to deliver one-quarter of the assessments, because in this case one-quarter is better than nothing. So she's delivered on two projects and partially delivered on one, which is the best-case scenario for her both practically and politically. She has executed the finishable and complex in a balanced way for maximum benefit.

Try this thought exercise for 1 day's work, marking each task on your daily list with one of the four categories listed in the delivery matrix above, and then choosing which actions to deliver based on what yields the best combination of practical and political benefit.

The next time you find yourself struggling to get dinner on the table by a certain time, ask yourself the following questions:

â

What part(s) of this meal

can

I serve on time?

â

Can I create or prepare something quickly to let people eat while they wait?

â

What is the best sequence of actions I can take that will get the rest of this meal delivered?

A delivery mentality means constant triage: keeping a nose for the deliverable and a sense of the expectations into which you're delivering.

WHY WE STOP AND STRATEGIES FOR CONTINUING

The problem of not finishing actions is actually a

failure to continue

. The reasons we failâwhy so many of us stop a project halfway through or within sight of the finish lineâvary, and each reason requires a different kind of solution.

Fatigue drains us.

Facing a mountain of work can exhaust our physical and mental resources. The solution for fatigue is rest. I cannot counsel working through exhaustion as a sustainable life strategy (even though a lot of professionals both in and outside of the kitchen treat it as if it were). Pushing through, as a delivery tactic, should be occasional or temporary. If extra toil is a periodic burden, then periods of extra rest should be your reward. I do advocate the following: First,

discern fatigue from fear.

Fear often masquerades as fatigue, with a similar physiology: heavy eyelids, sore muscles, even sleepiness. Real fatigue is to be respected. Fear-related fatigue often needs a cup of coffee, a pep talk, or a kick in the pants. Second,

calculate the value of a pause.

Will your work be so much more efficient after a pause that it will make up for the time it takes to ramp up again? Or will stopping nowâjust a few minutes or hours away from the finish lineâcreate even

more

work for you later? Will the mental benefits of pushing through now allow you to rest easier when the work is done? Or will working through exhaustion create more frustration and bad work? Of all the reasons to not finish, fatigue is the most legitimate. We need a consciousness of the reasons for fatigue and a measured response to it. For more strategies, see “Intentional Breaks” later in this chapter.

Fear, anger, and despair sabotage us.

Sometimes we lose confidence in our ability to complete a project. At other times anger or despair about our circumstances can drain our energy and drive us from our work. Whether we doubt our skill or our will, the solution in the face of fear, anger, or despair remains the same: to

take small forward steps,

to literally put one foot in front of the other, or move your arms and keep the fingers moving. Move slowly. It takes a while to discern whether our feelings are warranted or not, or whether those fears merit a course correction. In any case, you can't correct your course without movement. So keep moving. For more strategies about grappling with fear or despair, see “Combating Perfectionism” later in this chapter.

Ambition compels us.

Ambition is our inner executive chef run amok. The solution for those moments when our inner chef begins ordering us to do the next two things before we've finished the first is to

give ourselves a temporary “demotion.”

The chef needs to chill out for a bit. Put yourself in the mind-set of the employee, not the boss: Until these mushrooms are done, I'm a prep cook, not a chef. Until my project is done, I'm the assembly-line worker, not the executive. Remove your freedom to do something else.

Scatteredness confuses us.

We often leave tasks unfinished because our minds can't prioritize what's important. Somebody approaches us with a crisisâ

their

crisis, really, not oursâand we leave to help her while our time to finish dwindles. We're struck with an idea, something that can wait, and what ends up waiting is the original project we intended to finish. Or we get giddy upon receiving a bit of inspiration for our project, and in our excitement, we can't sit still to execute. The solution for confusion is

focus:

When you feel scattered, keep your eyes, literally, on your work. Make your body steady. Keep your feet planted. Try to block out or avoid external stimuli as much as you can.

Overconfidence tricks us.

We engage in magical thinking, an overestimation of our personal power and an underestimation of the rules of time and space. Overconfidence leads us to believe that we don't have to estimate the time it takes to complete a project, nor deliberately set aside the time for that work. Overconfidence is

why we don't start a project until it's too late and also why we get that “finish line syndrome” mentioned earlierâfor example, writing an e-mail but leaving the last few sentences or details for later. Two days later that e-mail remains incomplete and unsent on our desktop. Overconfidence rarely remembers that it takes time to ramp back up on a project once we've stopped it. The solution for overconfidence is

honesty with time,

the realization that we are all ruled by the laws of physics. Yes, sometimes we can do the impossibleâfitting a week's worth of work into a day, or being hit with a stroke of genius that simplifies or transforms the tasks before us, seemingly bending time and space to our will. Don't bank on those surreal moments. They come frequently only to those who've attained a degree of mastery in their field. Time and space do bend, but they bend for the engaged, not the disengaged.

When we examine our week and see many incomplete projects, we need to realize that one of the above emotions is likely preventing us from solidifying a delivery mentality.

Sometimes we can't finish, the truly urgent arises, or we just plain run out of time. When we know that we're going to be leaving loose ends, we try to find ways to tie them up for ourselves so that our physical and mental ramp-up time is minimized.

Some strategies:

â

Collect all the materials for the project and keep them in one place until you resume.

â

Jot down any thoughts that are at the top of your mind that you want to remember.

â

Schedule your session to resume the work, or set a reminder now to schedule one later.

â

Communicate your progress to partners or stakeholders to assess what remains to be done and whether help is available now or upon resumption.

The maxim to remember: Just as you want to begin with the end or stopping point in mind, you also want to end with the beginning or resumption in mind.

For example, author Ernest Hemingway made a habit of ending every writing session with the first sentence of the section he intended to write in the following session. In 1935 Hemingway wrote: “The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next.” This goes not only for writing but for a pause in any kind of project, something to reduce ramp-up time at the start of the next session and continue your momentum so that no task is altogether orphaned.

We should always be unblocking stuck projects so we can finish them. For every major goal, project, or mission, we should ask the question: What's stopping me from moving forward? What has stopped the process?

Sometimes an external process (for example, waiting for an approval) blocks us, and we must stop. But if we have the power to remove that block (for example, by sending an e-mail), our own hands can get that project rolling again. When we maintain a delivery mentality, we develop a nose for potential external blocks and try to avoid them. And if we cannot avoid themâif we must cede controlâwe try to work

with

those processes, removing or avoiding as many blocks as possible to our forward movement.

A great way to illustrate the concept of unblocking is something city dwellers deal with daily: commuting via mass transportation. When we travel by subway and bus, we face a succession of blocks to our forward movement, like turnstiles and lines. When we pass those blocks, we remain at the mercy of the intervals between trains or buses. So our goals at any stopping point are: (1)

minimize

the time spent waiting; and (2)

redeem

any time we must wait by using it to minimize our wait period at the next stopping point.