Wordcatcher (46 page)

Authors: Phil Cousineau

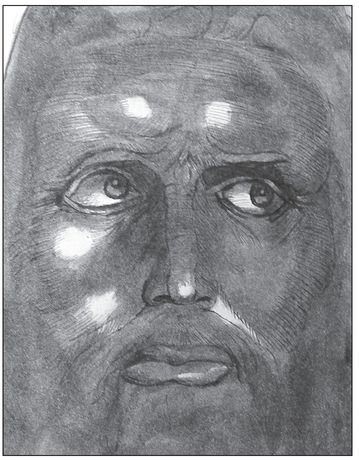

WISDOM

WISDOMSagacity, prudence, the quality of being wise.

From Old English

wis

, to see, and

dom

, quality or condition, hence, the quality of seeing; related to

witan

, to know, to wit. To “get

wise

” to Socrates meant to lead the well-lived life; to Dillinger it meant to “understand, learn something.” “Wise up” suggests that someone has been on the dullard side and needs to “get smart.” Companion words include

wiseacre

, a smart aleck, from the Middle Dutch

wijsseggheri

, soothsayer.

Wisdom tradition

has come to replace the loaded word

religion

for some scholars, such as Huston Smith. Figuratively,

wisdom

describes the capacity to act wisely, as in the famous couplet from the

Tao te Ching

: “A wise man has no extensive knowledge; He who has extensive knowledge is not a wise man.” Companion words include the marvelous

waywiser

, an indicator of the way, an adaptation of the Dutch

wegwijzer

, one who shows the way.

Wisdom

, then, can be “way out,” as hipsters chanted unwittingly over their bongos, or “way in,” as that Taoist hippie, Lao-Tzu, might’ve said.

From Old English

wis

, to see, and

dom

, quality or condition, hence, the quality of seeing; related to

witan

, to know, to wit. To “get

wise

” to Socrates meant to lead the well-lived life; to Dillinger it meant to “understand, learn something.” “Wise up” suggests that someone has been on the dullard side and needs to “get smart.” Companion words include

wiseacre

, a smart aleck, from the Middle Dutch

wijsseggheri

, soothsayer.

Wisdom tradition

has come to replace the loaded word

religion

for some scholars, such as Huston Smith. Figuratively,

wisdom

describes the capacity to act wisely, as in the famous couplet from the

Tao te Ching

: “A wise man has no extensive knowledge; He who has extensive knowledge is not a wise man.” Companion words include the marvelous

waywiser

, an indicator of the way, an adaptation of the Dutch

wegwijzer

, one who shows the way.

Wisdom

, then, can be “way out,” as hipsters chanted unwittingly over their bongos, or “way in,” as that Taoist hippie, Lao-Tzu, might’ve said.

Wisdom

WIT

WITInborn knowledge, natural or common sense, good humor, entertaining, lively intelligence.

It is not being too

facetious

to say that there are myriad expressions pertaining to wit, especially since

facetious

itself originally meant “mirthfully witty,” from Latin

facetiae

, and later meant “insincere.” Among the witty companion words are

inwit

, knowledge from within, conscience,

remorse

; and outwit, which first meant “knowledge from without, information,” and only later “to outmaneuver.” To be

fat-witted

is to be dull or stupid. A

flasher

is “one whose appearance of wit is an illusion.”

The Five Wits

are “the five sensibilities, namely common wit, imagination, fantasy, estimation, and memory.”

Unwit

means “ignorance”;

motherwit

, “natural talent”;

forewit

, “anticipation”;

gainbite/ayerbite

, the agenbite of inwit, “the backbiting of guilt.” A

witworm

is someone who feeds on others’

wit

. According to Herbert Coleridge, in

A Dictionary of the First, or Oldest Words in the English Language

(1859), an

afterwit

is an afterthought. Coleridge registers

biwit

as someone “out of one’s

wits

.” To Johnson, a

witling

was “a pretender; a man of petty smartness. One with little understanding or grace but desire to be funny.” In

Our Southern Highlanders,

Horace Kephart describes a

half-wit

as a silly or imbecilic person, writing, “Mountaineers never send their ‘

fitified

folks’ or

half-wits

, or other unfortunates, to any institution in the lowlands.” The witty Bill Bryson tracks

nitwit

down to the Americanization of the Dutch expression

Ik niet wiet,

“I don’t know.” The last (

witty

) word goes to John Florio, who translated Montaigne into English: “For he that hath not heard of Mountaigne yet / Is but a novice in the school of

wit

.”

It is not being too

facetious

to say that there are myriad expressions pertaining to wit, especially since

facetious

itself originally meant “mirthfully witty,” from Latin

facetiae

, and later meant “insincere.” Among the witty companion words are

inwit

, knowledge from within, conscience,

remorse

; and outwit, which first meant “knowledge from without, information,” and only later “to outmaneuver.” To be

fat-witted

is to be dull or stupid. A

flasher

is “one whose appearance of wit is an illusion.”

The Five Wits

are “the five sensibilities, namely common wit, imagination, fantasy, estimation, and memory.”

Unwit

means “ignorance”;

motherwit

, “natural talent”;

forewit

, “anticipation”;

gainbite/ayerbite

, the agenbite of inwit, “the backbiting of guilt.” A

witworm

is someone who feeds on others’

wit

. According to Herbert Coleridge, in

A Dictionary of the First, or Oldest Words in the English Language

(1859), an

afterwit

is an afterthought. Coleridge registers

biwit

as someone “out of one’s

wits

.” To Johnson, a

witling

was “a pretender; a man of petty smartness. One with little understanding or grace but desire to be funny.” In

Our Southern Highlanders,

Horace Kephart describes a

half-wit

as a silly or imbecilic person, writing, “Mountaineers never send their ‘

fitified

folks’ or

half-wits

, or other unfortunates, to any institution in the lowlands.” The witty Bill Bryson tracks

nitwit

down to the Americanization of the Dutch expression

Ik niet wiet,

“I don’t know.” The last (

witty

) word goes to John Florio, who translated Montaigne into English: “For he that hath not heard of Mountaigne yet / Is but a novice in the school of

wit

.”

WORDFAST

WORDFASTTrue to one’s word

. What would a word book be without a few “word” words? Fellow words include

wordridden

, to be a slave to words you don’t understand, and

wordwanton

, having a dirty mouth. A

wordmonger

is a show-off with

words, rather than using them to express meaning, emotion, facts. A

witherword

is hostile language. One blessed with word dexterity is a

logodaedalus

, after the Greek

logo

, word, and

Daedalus

, the inventor of the

labyrinth

, armor, and toys. Someone stricken with

logophilia

has caught the love of words; whereas

logomachy

is a fight or dispute over words. A

wordroom

is a place to indulge our passions for words, closely related to

lectory

, a place for reading. A

scriptorium

was a

translation

hall in medieval Ireland. A “lexicographical laboratory” was a backyard shed in London where James Murray and friends created

The Oxford English Dictionary

over the course of 49 years, comprising twelve volumes and 414,825 words, plus 1,827,306 citations to illuminate their meanings. “Words, words, words,” cries Eliza Doolittle in

My Fair Lady,

“I’m so sick of words!” On the other hand, the Divine Sarah Bernhardt longed for them, as she wrote to her lover, Victorien Sardou, “Your

words

are my food, your breath my wine. You are everything to me.”

. What would a word book be without a few “word” words? Fellow words include

wordridden

, to be a slave to words you don’t understand, and

wordwanton

, having a dirty mouth. A

wordmonger

is a show-off with

words, rather than using them to express meaning, emotion, facts. A

witherword

is hostile language. One blessed with word dexterity is a

logodaedalus

, after the Greek

logo

, word, and

Daedalus

, the inventor of the

labyrinth

, armor, and toys. Someone stricken with

logophilia

has caught the love of words; whereas

logomachy

is a fight or dispute over words. A

wordroom

is a place to indulge our passions for words, closely related to

lectory

, a place for reading. A

scriptorium

was a

translation

hall in medieval Ireland. A “lexicographical laboratory” was a backyard shed in London where James Murray and friends created

The Oxford English Dictionary

over the course of 49 years, comprising twelve volumes and 414,825 words, plus 1,827,306 citations to illuminate their meanings. “Words, words, words,” cries Eliza Doolittle in

My Fair Lady,

“I’m so sick of words!” On the other hand, the Divine Sarah Bernhardt longed for them, as she wrote to her lover, Victorien Sardou, “Your

words

are my food, your breath my wine. You are everything to me.”

WRITE

WRITETo make a mark; to record, communicate.

“To trace symbols representing word(s),” says

The Concise Oxford Dictionary

, “especially with pen or pencil on paper or parchment.” For as long as we have known, human beings have felt a compunction to record their thoughts, to reach out to one another using the magical letters of their respective alphabets. This effort began with a simple scratch on bark,

or papyrus, which, incidentally, later gave us the word

paper

. It makes poetic sense, then, that the root of our word

write

is

writan

, Old English for “scratch.” Ogden Nash’s quip comes to mind: “Happiness is having a scratch for every itch.” Look that up and you’ll soon find “scratch” as a synonym for “money,” though

writing

for “scratch” has eluded many a writer trying to “scratch out a living.” Incidentally, “starting from scratch” refers to making a mark in the dirt for the start of a race, which is often then

written

about. And what do we

write

with? A

ballpoint pen

, which was originally called a “non-leaking, high-altitude

writing

stick.” When I first read that, I had to scratch my head before

writing

it down. As for the

secret

of

writing

, I was taught that

writing

is rewriting is rewriting. When an interviewer asked S. J. Perelman how many drafts of a story he was used to

writing

, the gag man for the Marx Brothers and others replied: “Thirty-seven. I once tried doing thirty-three, but something was lacking, a certain—how shall I say?—

Je ne sais quoi

.”

“To trace symbols representing word(s),” says

The Concise Oxford Dictionary

, “especially with pen or pencil on paper or parchment.” For as long as we have known, human beings have felt a compunction to record their thoughts, to reach out to one another using the magical letters of their respective alphabets. This effort began with a simple scratch on bark,

or papyrus, which, incidentally, later gave us the word

paper

. It makes poetic sense, then, that the root of our word

write

is

writan

, Old English for “scratch.” Ogden Nash’s quip comes to mind: “Happiness is having a scratch for every itch.” Look that up and you’ll soon find “scratch” as a synonym for “money,” though

writing

for “scratch” has eluded many a writer trying to “scratch out a living.” Incidentally, “starting from scratch” refers to making a mark in the dirt for the start of a race, which is often then

written

about. And what do we

write

with? A

ballpoint pen

, which was originally called a “non-leaking, high-altitude

writing

stick.” When I first read that, I had to scratch my head before

writing

it down. As for the

secret

of

writing

, I was taught that

writing

is rewriting is rewriting. When an interviewer asked S. J. Perelman how many drafts of a story he was used to

writing

, the gag man for the Marx Brothers and others replied: “Thirty-seven. I once tried doing thirty-three, but something was lacking, a certain—how shall I say?—

Je ne sais quoi

.”

WRITHE

WRITHETo twist and turn in acute pain

. One of J. R. R. Tolkien’s favorite words, a 12th-century one from Middle English, from Old English

wruthan

; akin to Old Norse

rutha

, to twist into coils or folds or twist into distortion. Tolkien’s avid studies in Anglo-Saxon (he was the world expert on

Beowulf

) provided the inspiration for his famously evil

wraiths

in

The Lord of the Rings

, which are the very embodiment—or enspiritment—of

wrenching, wrangling, and writhing.

Companion words include

wraith

, vividly defined by Mackay as “the supposed apparition of the soul about to quit the body of a dying person.” Curiously related is

twistification

, cited in

Southern Appalachian Slang

as a “pejorative term for dancing used by churchmen. Wherever the church has not put its ban on twistifications the country dance is the chief amusement of young and old.”

. One of J. R. R. Tolkien’s favorite words, a 12th-century one from Middle English, from Old English

wruthan

; akin to Old Norse

rutha

, to twist into coils or folds or twist into distortion. Tolkien’s avid studies in Anglo-Saxon (he was the world expert on

Beowulf

) provided the inspiration for his famously evil

wraiths

in

The Lord of the Rings

, which are the very embodiment—or enspiritment—of

wrenching, wrangling, and writhing.

Companion words include

wraith

, vividly defined by Mackay as “the supposed apparition of the soul about to quit the body of a dying person.” Curiously related is

twistification

, cited in

Southern Appalachian Slang

as a “pejorative term for dancing used by churchmen. Wherever the church has not put its ban on twistifications the country dance is the chief amusement of young and old.”

X

XENOGENESIS

XENOGENESISOther books

The House at the Bottom of the Hill by Jennie Jones

Un punto y aparte by Helena Nieto

Job by Joseph Roth

The French Detective's Woman by Nina Bruhns

The Guardian (The Gifted Book 1) by C. L. McCourt

The Snares of Death by Kate Charles

Slocum and the Diamond City Affair (9781101612118) by Logan, Jake

While My Eyes Were Closed by Linda Green

Sharpe's Regiment by Bernard Cornwell