Wordcatcher (14 page)

Authors: Phil Cousineau

CATCH

CATCHAn 800-year-old word used to describe a game that’s been played for at least thousands of years. Recent excavations along the Nile reveal Egyptian tomb paintings forty-five centuries old of a pharaoh playing catch with his priests and swinging a black stick at a palm-leaf-wrapped ball. Compared with that veteran status, our English word

catch

is a rookie, first brought up from the minor leagues of language in 1205 AD. The sequence is familiar to all hunters and ballplayers.

Catch

ricochets to us from Old French

cachier

, to hunt, chase, from the Latin

captare

, to seize, and

capere

, to take hold. Thus, to

catch

is to take hold of what has been chased down, whether a long belt to left field or a long-tailed rabbit. The expression “a good

catch

” took on romantic connotations at the end of the 16th century as a way to describe a nubile young woman or a winsome lad as someone “worth

catching

.” Jane Austen adapted the phrase for one of her characters who was vying “to

catch

the eye” of someone who had caught hers. Companion words include

capable

, meaning “with ability,” and

catchy

, memorable.

Catchword

is a dictionary term for a word printed in the lower right-hand corner of each page of a book that signals what the first word will be on the following page.

Catchy

phrases include

catch as catch can,

recorded in 1393, and the foot-tapping song “Catch Me If You Can,” recorded by the Dave Clark Five in 1965.

Catch-22

, Joseph Heller’s famous novel title, refers to a notorious “

catch

” (or gotcha) in military law that relates to a bomber

pilot’s decision to fly or not to fly combat missions. If the pilot never asks to be relieved, he can be officially regarded as insane—and thus eligible to be grounded. But if he does ask, it is interpreted as him having the wherewithal to recognize the danger involved, a sign that he isn’t

crazy

. So he has to keep flying more missions. And there is the lesser-known, but to some of us just as stirring, “Catch 25.” Legend has it that during a break on the set of

Citizen Kane

the 25-year-old Orson Wells shouted: “Who’s got a baseball? Let’s play

catch

!” Finally, there is

wordcatcher

, an alert reader who is always ready for the coruscating

catch

of a particularly beautiful, unusual, precise, or eye-opening word in a book or

conversation

—and then equally ready to throw it over to the next reader, a playful act that keeps the game of

wordcatching

going on, infinitely.

catch

is a rookie, first brought up from the minor leagues of language in 1205 AD. The sequence is familiar to all hunters and ballplayers.

Catch

ricochets to us from Old French

cachier

, to hunt, chase, from the Latin

captare

, to seize, and

capere

, to take hold. Thus, to

catch

is to take hold of what has been chased down, whether a long belt to left field or a long-tailed rabbit. The expression “a good

catch

” took on romantic connotations at the end of the 16th century as a way to describe a nubile young woman or a winsome lad as someone “worth

catching

.” Jane Austen adapted the phrase for one of her characters who was vying “to

catch

the eye” of someone who had caught hers. Companion words include

capable

, meaning “with ability,” and

catchy

, memorable.

Catchword

is a dictionary term for a word printed in the lower right-hand corner of each page of a book that signals what the first word will be on the following page.

Catchy

phrases include

catch as catch can,

recorded in 1393, and the foot-tapping song “Catch Me If You Can,” recorded by the Dave Clark Five in 1965.

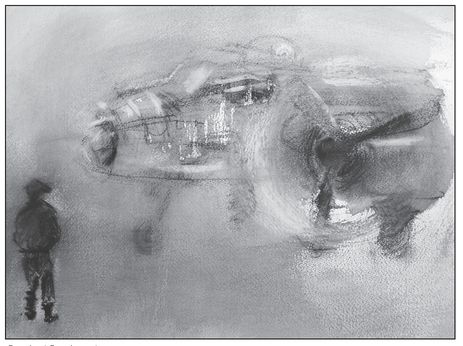

Catch-22

, Joseph Heller’s famous novel title, refers to a notorious “

catch

” (or gotcha) in military law that relates to a bomber

pilot’s decision to fly or not to fly combat missions. If the pilot never asks to be relieved, he can be officially regarded as insane—and thus eligible to be grounded. But if he does ask, it is interpreted as him having the wherewithal to recognize the danger involved, a sign that he isn’t

crazy

. So he has to keep flying more missions. And there is the lesser-known, but to some of us just as stirring, “Catch 25.” Legend has it that during a break on the set of

Citizen Kane

the 25-year-old Orson Wells shouted: “Who’s got a baseball? Let’s play

catch

!” Finally, there is

wordcatcher

, an alert reader who is always ready for the coruscating

catch

of a particularly beautiful, unusual, precise, or eye-opening word in a book or

conversation

—and then equally ready to throw it over to the next reader, a playful act that keeps the game of

wordcatching

going on, infinitely.

Catch

(Catch 22)

(Catch 22)

CHANTEPLEURE (FRENCH)

CHANTEPLEURE (FRENCH)To sing and cry at the same time.

A word to fill a void in our language, one that we’ve all felt and rarely been able to describe. Recall the time you attended your child’s school Christmas concert and when the sing-along time came at the end, with

O Holy Night,

you could barely lift your voice for all the emotion swelling in your heart. No English word fills the need to describe that beveled-edge moment on the verge of both elation and sorrow. But there is the lovely

chantepleure

in French, which defies precise derivation, other than from

chanter

, to sing, and

pleurer

, to weep. Perhaps it is the result of centuries of concerts in the bejeweled Saint-Chapelle, in Paris, or in that stone poem, Chartres Cathedral, or the triumphant tears inspired by the singing of “La Marseillaise” in the French classic

Les Enfants du Paradise

. Whatever its source,

chantepleure

is to language what sweet-and-sour sauce is to Chinese food. Companion words include

chanticleer

, clear-singing, as well as

Chauntecleer

, the proud rooster in the French fable

Reynard the Fox

. During the French invasion of Russia in 1812, those Russian prisoners who did not sing for their French captors were insulted as

chanterapa

. Then there’s

merry-go-sorry

, a merry-go-round of emotion, spinning you around from laughter to weeping. Synchronicity lives: as I type this word story, my son Jack brushes by me, casually chanting “Singin’ in the Rain,” the American equivalent of singing through your tears.

A word to fill a void in our language, one that we’ve all felt and rarely been able to describe. Recall the time you attended your child’s school Christmas concert and when the sing-along time came at the end, with

O Holy Night,

you could barely lift your voice for all the emotion swelling in your heart. No English word fills the need to describe that beveled-edge moment on the verge of both elation and sorrow. But there is the lovely

chantepleure

in French, which defies precise derivation, other than from

chanter

, to sing, and

pleurer

, to weep. Perhaps it is the result of centuries of concerts in the bejeweled Saint-Chapelle, in Paris, or in that stone poem, Chartres Cathedral, or the triumphant tears inspired by the singing of “La Marseillaise” in the French classic

Les Enfants du Paradise

. Whatever its source,

chantepleure

is to language what sweet-and-sour sauce is to Chinese food. Companion words include

chanticleer

, clear-singing, as well as

Chauntecleer

, the proud rooster in the French fable

Reynard the Fox

. During the French invasion of Russia in 1812, those Russian prisoners who did not sing for their French captors were insulted as

chanterapa

. Then there’s

merry-go-sorry

, a merry-go-round of emotion, spinning you around from laughter to weeping. Synchronicity lives: as I type this word story, my son Jack brushes by me, casually chanting “Singin’ in the Rain,” the American equivalent of singing through your tears.

CHARACTER

CHARACTERAn impressive life; the life that is incised on the soul

. A sharp word with an incisive story. I’m reminded of the description of the face of a lovely old woman in Ballyconneelly, Connemara, where I lived in the 1980s. My neighbor, Mr. Keaney, called it a “lived-in face.” Originally, a

kharacter

was an engraving or stamping tool in ancient Greece, deriving from the verb

kharassein

, to sharpen, cut, incise, furrow, scratch, engrave. In Skeat’s dictionary of 13th-century

slang

,

character

has the meaning of “an engraved or stamped mark.” Not used in its modern sense of “distinctive qualities” until the 17th century, by the historian Clarendon (

History of Great Rebellions

), and later in the 18th century, when Noah Webster defines

character

as qualities that are “impressed by nature or habit” onto someone, distinguishing them from someone else. Thus, the early sense of

kharacter

, “to impress or stamp in a way that marked one thing differently from another,” has been likewise stamped deep into the language.

Character

is the etching of life’s trials and tribulations into our faces and souls, which distinguishes us from everyone else. Eventually, this sense led to

character drawings

and

character portraits

in literature and memoirs, and to

character acting

. The French essayist Michel de Montaigne wrote, “To compose our

character

is our duty, not to compose books, and to win, not battles and provinces, but order and tranquility in our conduct. Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live appropriately.” UCLA basketball coach John Wooden said, “Sports

don’t build

character

; they reveal it.” Annie Lamott, in

Bird by Bird

, writes, “Find out what your

character

cares about the most in the world, because then you will have discovered what’s at stake.” An obscure but compelling meaning for

character

, in Skeats, is as a synonym for “handwriting,” a belief that lives on in the work of handwriting experts. Companion words include

characteristics

and

character flaw

.

. A sharp word with an incisive story. I’m reminded of the description of the face of a lovely old woman in Ballyconneelly, Connemara, where I lived in the 1980s. My neighbor, Mr. Keaney, called it a “lived-in face.” Originally, a

kharacter

was an engraving or stamping tool in ancient Greece, deriving from the verb

kharassein

, to sharpen, cut, incise, furrow, scratch, engrave. In Skeat’s dictionary of 13th-century

slang

,

character

has the meaning of “an engraved or stamped mark.” Not used in its modern sense of “distinctive qualities” until the 17th century, by the historian Clarendon (

History of Great Rebellions

), and later in the 18th century, when Noah Webster defines

character

as qualities that are “impressed by nature or habit” onto someone, distinguishing them from someone else. Thus, the early sense of

kharacter

, “to impress or stamp in a way that marked one thing differently from another,” has been likewise stamped deep into the language.

Character

is the etching of life’s trials and tribulations into our faces and souls, which distinguishes us from everyone else. Eventually, this sense led to

character drawings

and

character portraits

in literature and memoirs, and to

character acting

. The French essayist Michel de Montaigne wrote, “To compose our

character

is our duty, not to compose books, and to win, not battles and provinces, but order and tranquility in our conduct. Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live appropriately.” UCLA basketball coach John Wooden said, “Sports

don’t build

character

; they reveal it.” Annie Lamott, in

Bird by Bird

, writes, “Find out what your

character

cares about the most in the world, because then you will have discovered what’s at stake.” An obscure but compelling meaning for

character

, in Skeats, is as a synonym for “handwriting,” a belief that lives on in the work of handwriting experts. Companion words include

characteristics

and

character flaw

.

CHICANERY

CHICANERYTricky talk, clever deceptions, unfair artifice

. The deliberate practice of obscuring the truth that this tough-sounding word evokes is similar to the speculation about the word itself. The root word here is the unfortunately lost verb

chicane

, from French

chicaner

, to deceive, to wrangle. But the stratagem within chicanery reaches back to

chicane

, a dispute in the French bridge game described as “a whist hand without trumps.” The modern French verb retains the smoky atmosphere of an argument in a tense card game, “to quibble.” Skeat tracks it back even further to the Persian

chuan

, a crooked mallet, from

mall

, a club or bat. Still others insist it is an echo of a precursor to golf played long ago in Languedoc. In his day John Adams captured the pettifoggery of politics: “Abuse of words has been the great instrument of sophistry and chicanery, of party, faction, and division of society.” The 19th-century Romantic novelist Ouida (a favorite of Oscar Wilde’s) wrote, “To vice, innocence must always seem only a superior kind of chicanery.”

. The deliberate practice of obscuring the truth that this tough-sounding word evokes is similar to the speculation about the word itself. The root word here is the unfortunately lost verb

chicane

, from French

chicaner

, to deceive, to wrangle. But the stratagem within chicanery reaches back to

chicane

, a dispute in the French bridge game described as “a whist hand without trumps.” The modern French verb retains the smoky atmosphere of an argument in a tense card game, “to quibble.” Skeat tracks it back even further to the Persian

chuan

, a crooked mallet, from

mall

, a club or bat. Still others insist it is an echo of a precursor to golf played long ago in Languedoc. In his day John Adams captured the pettifoggery of politics: “Abuse of words has been the great instrument of sophistry and chicanery, of party, faction, and division of society.” The 19th-century Romantic novelist Ouida (a favorite of Oscar Wilde’s) wrote, “To vice, innocence must always seem only a superior kind of chicanery.”

CHIRM, CHYRME

CHIRM, CHYRMEMelancholic birdsong

. A word you never thought possible for a moment you thought could never be expressed with mere language. Have you ever been outdoors in those air-crackling moments just before a rainstorm when a branch full of birds in a nearby tree begins to chirp or sing? Well, this is the word, in the lovely phrasing of the 18th-century Scottish wordhunter Joseph Jamieson, “the mournful sound emitted by them, especially when collected together.” The OED’s definition is dolefully prosaic, chiming in with “noise, din, chatter, vocal noise, especially birds, with a secondary meaning of the noise of children on a playground, especially the mingled noise of many birds.” Murray’s anonymous contributor for this word must not have been fond of birdsong. Curious companion words include

jargon

, from Old French

jargoun

, twittering of birds. The Scottish

chavish

is second cousin to

chyrme

, defined by Rev. W. D. Parish as “a chattering or prattling noise of many persons speaking together. A noise made by a flock of birds.” We may collect these marvelous bird words in a “birdcage,” which in French is

cajole

, which gave us

cajoler

, to persuade by flattery or promises or to chatter like a blue jay. These words are birds-of-a-feather, what I like to think of as “observation words” that emerged from a lifetime of closely watching nature’s own theater, including bird behavior. It’s sweet to think that our own mating calls may have been inspired by untold generations listening to the cajoling, the flattery, the sweet-nothings

of our fair-feathered friends, the birds, which adds a grace note to the romantically alluring power of Frank Sinatra’s crooning or Ella Fitzgerald’s scatting.

. A word you never thought possible for a moment you thought could never be expressed with mere language. Have you ever been outdoors in those air-crackling moments just before a rainstorm when a branch full of birds in a nearby tree begins to chirp or sing? Well, this is the word, in the lovely phrasing of the 18th-century Scottish wordhunter Joseph Jamieson, “the mournful sound emitted by them, especially when collected together.” The OED’s definition is dolefully prosaic, chiming in with “noise, din, chatter, vocal noise, especially birds, with a secondary meaning of the noise of children on a playground, especially the mingled noise of many birds.” Murray’s anonymous contributor for this word must not have been fond of birdsong. Curious companion words include

jargon

, from Old French

jargoun

, twittering of birds. The Scottish

chavish

is second cousin to

chyrme

, defined by Rev. W. D. Parish as “a chattering or prattling noise of many persons speaking together. A noise made by a flock of birds.” We may collect these marvelous bird words in a “birdcage,” which in French is

cajole

, which gave us

cajoler

, to persuade by flattery or promises or to chatter like a blue jay. These words are birds-of-a-feather, what I like to think of as “observation words” that emerged from a lifetime of closely watching nature’s own theater, including bird behavior. It’s sweet to think that our own mating calls may have been inspired by untold generations listening to the cajoling, the flattery, the sweet-nothings

of our fair-feathered friends, the birds, which adds a grace note to the romantically alluring power of Frank Sinatra’s crooning or Ella Fitzgerald’s scatting.

Other books

Winter's Kiss by Williams, DS

La chica del tambor by John Le Carré

Billion Dollar Wood by Sophia Banks

Blood Legacy Origin of Species by Kerri Hawkins

El frente by Patricia Cornwell

Fourteen Days by Steven Jenkins

To Catch a Rake by Sally Orr

The Sister and the Sinner by Carolyn Faulkner

Wild Gratitude by Edward Hirsch

Blooming Crochet Hats by Graham, Shauna-Lee