Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (21 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

Ursula Kay was a senior PI working in the Aircraft Section.

With this information the Section built up a comprehensive dossier, constantly updated, on the state of the German aircraft industry, with the location of their factories and the types and numbers of aircraft built. This became particularly important from mid-1943, when it was realised that enemy aircraft factories were being dispersed to the eastern regions of Germany where they were at the extreme range of Allied bombers and, it was hoped, subject to fewer attacks. It also meant that new aircraft developments were more easily concealed from reconnaissance aircraft. An added twist to this dispersal programme was that the enemy left the original factories empty but intact, with the appearance of production going on, hoping that Allied bombs would be wasted on attacking them.

High priority was given to attacks on German aircraft assembly factories, where newly completed fighters could be destroyed before they became operational. In 1943, Constance became involved in behind-the-scenes work in the preparations for daylight bombing operations by Flying Fortress aircraft of the US 8th Air Force. She wrote:

The work on aircraft factories that I shared with Charles Sims was at once injected with a sense of urgent responsibility. Those scraps of evidence that we pieced together like a jig-saw puzzle – a glimpse of a fuselage outside an assembly shop, the coming and going of lorries at loading bays, the floor areas of the workshops, the positions of the aircraft (which we found usually meant much more than mere numbers) – the meaning we found in all these things was going to be weighed against the lives of the Fortress crews.

It took months of patiently re-checking photographs of the German eastern borders that had been taken in previous years, and comparison with more recent sorties, before the Aircraft Section was able to provide the vital information on a new Focke-Wulf assembly factory constructed at Marienburg in East Prussia. On 9 October 1943, in a daylight precision raid, the USAAF successfully attacked the factory and put it out of action. By the spring of 1944 the enemy’s aircraft production was seriously affected and Allied air supremacy over Germany was established for the first time.

Constance and her team were also responsible for identifying two revolutionary German-designed aircraft. Speed and the attainment of height and manoeuvrability in fighter and reconnaissance aircraft remained the essential qualities that enabled the Allied pilots to ‘nip in and nip out’ and retain the edge over their opponents. For some time the Spitfire could out-perform any other aircraft but by the end of 1943 the updated German Focke-Wulf fighter, the Fw 190, the prototype of which had been spotted by the Aircraft Section two years earlier, was challenging this claim. Fortunately a new, faster PR Spitfire was by then ready to go into service, and Allied superiority was retained.

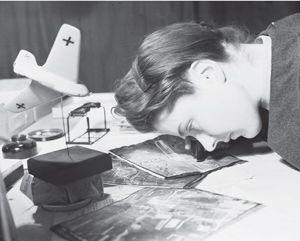

In the summer of 1943, the Aircraft Section was instructed to watch for ‘anything queer’ on the photographs they examined of the experimental testing site at Peenemunde on the German Baltic coast, where secret weapons were being developed. Photographs taken in June in bright, clear weather helped to confirm the nature of these secret weapons, but Constance was far more interested in something else she had spotted on those same photographs: four little tail-less aeroplanes, which she considered ‘queer enough to satisfy anybody’. These were measured and later identified as Me 163 rocket fighters, the only liquid-fuel rocket aircraft ever to fly operationally. They had a performance far exceeding that of contemporary piston-engine fighter aircraft, such as the Spitfire, taking off at a speed of 200mph and accelerating to pull up into a near-vertical climb to reach altitudes of 39,000ft in 3 minutes. When it began active combat in May 1944, it was a threat to all Allied operations, including the forthcoming Normandy invasion. Pictures of Constance at work show that she kept a wooden model of the Me 163 on her desk.

The early identification of the aircraft gave time for Allied air crews to be briefed on its attacking tactics and to prepare defensive measures. It was the Me 163’s own impressive performance that limited its effective use as, having reached its slower-moving targets in a matter of seconds, it was then going too fast to fire at them accurately. It also needed a far bigger turning circle than any other fighter aircraft in order to return to the fray or return to base for refuelling, giving time for slower but more manoeuvrable aircraft to escape or vanish into a cloud.

Constance Babington Smith, head of the Aircraft Section, with a model of the Me 163 rocket fighter on her desk.

At take-off, jet-propelled aircraft left pairs of fan-shaped scorch marks or long dark streaks on the ground and this distinctive clue enabled the Aircraft Section to locate other sites where similar marks were present. This led to their identification of the Me 262, a twin-engine jet-powered fighter considered to be the most advanced German aviation design in use during the Second World War. It could fly for 60–90 minutes with a cruising speed of up to 50mph faster than piston-engine fighters, including the Spitfire, and posed a very real threat to Allied operations in the last months of the war. At the same time Constance’s team confirmed that Me 262s were being built in underground factories at Kahla. Fortunately only 200 Me 262s made it into combat due to fuel shortages. The Allies dealt with their threat by ground attacks and precision-bombing raids on the synthetic oil plants, which by then were the only means of German fuel production.

The long hours of all-absorbing scrutiny through a stereoscope were relieved by breaks in which the PIs could walk in the garden, gaze at the river or relax with a chat and a cigarette. One day of the week, though, was special at Medmenham because Wednesday was doughnut day! Suzie Morgan remembered:

Every Wednesday the Americans used to get quite excited and form a long queue at the Red Cross kiosk where they could buy real doughnuts, made fresh on the spot, served with coffee. We Brits used to laugh that it meant so much to them but I suppose it reminded them of home.

7

The Americans introduced many people to new foods and new ways of eating it. Myra Murden said:

They were a lovely crowd. It seemed to us that they mixed all their food together but as they said, ‘It all goes down the same way’. I remember how they toasted marshmallows on the fire which were really delicious.

8

‘Panda’ Carter recalled that:

The Americans introduced us to raspberry jam with bacon, and peanut butter with blackcurrant jam.

9

Aircraft need airfields, and a Third-Phase Airfield Section was established early in 1940 at Wembley. With the move to Medmenham, the Section was designated as ‘C’ and headed by Section Officer Ursula Powys-Lybbe, a professional photographer before the war, with a studio in Cairo and later a successful business based in London. In July 1939, when war seemed inevitable, she gave up her business and joined the Auxiliary Fire Service in London, hoping to be usefully employed. Through the following Phoney War winter there was little for her to do so she resigned and went to stay with a friend who lived in Medmenham village. By a series of coincidences, she joined the WAAF, worked as a records clerk until her selection for PI training, and joined RAF Medmenham on 1 April 1941.

Airfield interpretation revealed not only the enemy’s current status but also their future plans. The resources invested in airfield construction, with its associated buildings and communications, indicated an important strategic purpose. Early in the war, the Germans constructed standardised ‘tailor-made’ airfields, and PIs could deduce the function of the units based there – whether for bomber, mine-laying, fighter or transport aircraft – from the variety of installations in place. These distinctive clues could be applied to other existing or newly built airfields, landing grounds and seaplane bases in enemy or occupied territory. Regular monitoring ascertained if any airfield was being modified for a change of purpose.

Jane Cameron, the shy Scot who had worked in Coastal Command with a crowd of ‘rumbustious’ airwomen, was commissioned in August 1941, then posted to Medmenham. She wrote in her diary:

I suppose people keep diaries – or begin to keep diaries – for all sorts of different reasons, so I imagine getting one’s commission in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force is as good a reason as any other. Not that I ever imagined having a commission would be anything like this. When one is in the ranks of the WAAF, the ‘officers’ are a class apart. This is regardless of education or social standing in civilian life – everything. In the service, there are ‘the officers’ and ‘the other ranks’ and no matter how much of a social renegade one is, no matter how complete one’s scorn of social custom, this becomes part of one’s service mentality. One accepts the officers as a race apart.

On my appointment, I came down from Leuchars to London in a dazed condition, by the night train, in the company of half a dozen sailors and drank beer with increasing solemnity all the way from Edinburgh to London. Occasionally I told myself that this was the last journey of this sort that I would make. This was the end of irresponsibility – that ruling characteristic of all rankers. From now on, I would be ‘an officer’. It would be autre temps, autre moeurs. I felt a little sad about it all.

In London, I dumped my bags at a boarding house near Marble Arch and went shopping. That same evening, I stepped out of my boarding house on to the Edgware Road, an officer down to the second kid glove carried in the gloved left hand. At Marble Arch, an airman saluted me. I was now one of those ‘up there’. I had left the ranks behind. I was overcome with melancholy.

10

Despite professing a preference for ships over aircraft on her PI course, ‘Jane’ was posted to the Airfield Section, which seems to have been her choice:

I passed that course in the end, and I got the job I wanted in this comic unit, and now, after six months of it, I am beginning to feel that I know a little more about it. So much to learn, and such mentally exhausting learning too! We are now in a new Mess at Henley, (Phyllis Court) full of priceless people – Anne Whiteman, an Oxford Don-ess, Lady Bonham Carter, a charming and intelligent eccentric, Vyvyan Russell [sic] who has a face like Dolores – our Lady of Pain – utterly beautiful. Ursula Powys-Lybbe, the most modern of hyper-sensitive moderns, who has much of my own uncomfortable flair for seeing round all the mental screens behind which people hide their motives from themselves and the world. I love her dearly. Then there is Babs Babington Smith who I am only now beginning to know, due to her admitted façade of other worldliness which I privately think a little precious but which is none of my business and anyhow I like her in spite of it – I wouldn’t like her if the otherworldliness were

real

, by the way.