Wolf's-head, Rogues of Bindar Book I

Read Wolf's-head, Rogues of Bindar Book I Online

Authors: Chris Turner

Tags: #adventure, #magic, #sword and sorcery, #epic fantasy, #humour, #heroic fantasy, #fantasy adventure

Rogues of

Bindar Book I

Chris

Turner

Copyright 2011 Chris Turner

Cover Design: Chris Turner

Published by Innersky Books on Smashwords

Discover other titles by Chris Turner at

Smashwords.com

This is a work of fiction. All the characters

and events portrayed in these stories are either fictitious or are

used fictitiously.

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If

you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not

purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com

and purchase your own copy.

It was in a dream that illumination dawned.

Escape was so simple! Humiliating months of hard labour in a

rag-tag gang of scoundrels had made him grim and cunning. As he

chipped away at the mortar of the wall’s one loosened rock, the

magical gladius gleamed. He reflected on how his curiosity for the

arcane, his thirst for adventure had brought him to such an

unexpected pass.

If only the cursed allure of the circus

tents, the entertainments of the performers had not drawn him into

a break from routine.

The stone gave way. Now there was no turning

back . . .

1

MIRACULA AT HEAGRAM FAIR

From

Chaplain’s modern guide to misconceived terms:

“

Enchanter:

One who brings plausibility to the most farfetched acts,

fascinating the eye, the ear, and creating a sense of ‘suspended

wonder’.

Common

methods: sleight of hand, illusion, dissembling, hypnotism,

alteration. Held in general contempt are snake-charming, hoaxing,

trained owls, talking amulets and the like . . .

”

I

Grey listless

morn. A questionable time to be out catching rockgobblers on the

beach, but here he was, Baus, a handsome youth, watching the surf

lick the sand like mischievous serpents’ tongues. He had sea-green

eyes, a tinge of swarthiness, a jauntiness to step, a canniness to

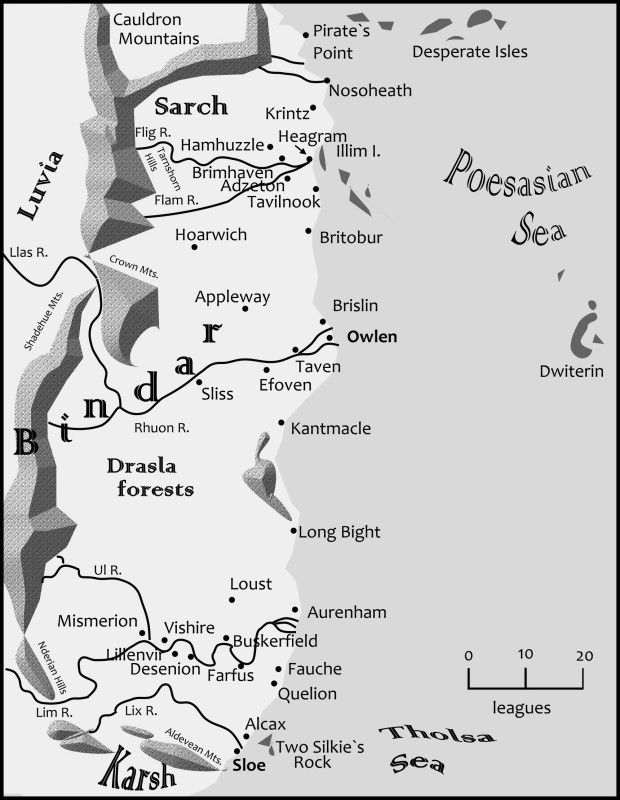

gaze, an affability of voice. Not far from Heagram’s port, the

beach stretched languidly, as did the sea, a quilt of deepest aqua.

The drab, chill stillness promised nothing to improve Baus’s

spirit.

While his

creative faculties wandered over the less-than-optimal

circumstance, he scuffed at the tow line anchored fast in the sand.

Only yesterday he had been upbraided by Harky the shoremaster for

inadequate productivity, namely, a measly dredging up of only four

rockgobblers and two nibblers. Baus had impressed on the

shoremaster’s mind the damaging effect of negative affirmations,

but had received only stern reprimands in return.

He thrust

himself back to his grey reality. The matted tangle of nets stunk

of rotten fish; the joints were braced with iron, fickle with rust,

causing his fingertips to bleed. Swoops of lavender cloud hung in

swirls of muted colour. Northward ran a shoreline the hue of wharf

planks; to the south, a broad expanse of mud flats, dark and slick

in low tide. Almost at the edge of his vision, he discerned smoke

rings—dragging above the low cluster of stone and timber buildings,

the salt-washed precincts of Heagram.

Baus pulled

back at the dark masses of his hair, scowling. Was there any way to

get out of this dreary loop? He had a quick mind, deft hands, even

a sensitive soul—how could he not try his luck at another

occupation?

The idea

seemed grandiose. He fingered his loose ponytail trailing down his

back. Who was to say he would be any better off elsewhere?

Grimacing,

Baus pounded the pair of brickboar breeches clinging to his thighs.

He grunted at their sea-drenched and patched quality. Despite their

disrepair, they fitted him admirably, accentuating his lean figure.

A sea charm of translucent green hung on a cord about his neck, a

gift from his father, very similar to a companion piece he kept in

his pocket won in a dice match of ‘Varlets and Vixens’. He recalled

the time well on Heagram’s quayside in

Snogmald Tavern

, his

victory over a pair of ribald Brislin boatswains.

Normally he

would be out sailing the

Calaan

—sheeting the one-masted

fishing sloop and trawling for gallfish or snogmald, but the boat

was currently hoisted on the wharf, facing repairs—the underbelly

had been recklessly driven close to Fiddler’s reef and a hole was

staved in her stern. As a result he was relegated to baiting the

rockgobbler traps and repairing the gallfish nets and searching for

razor clams and the odd mollusc which happened to wash upon the

shore . . .

A league out

to sea blossomed Illim Island whose cypress-rich mystery cast dull

shadows upon the swells.

Baus lay down

his paltry basket of catches and slumped himself down on a wet

rock. A few lubberly scows bobbed out in the harbour—odd shapes

which he recognized as Mesmelter’s cog, Jubben’s

Gobblerbane

and Leaster’s

Windfall

. A large carrack rode the deeps—her

high hull riding proudly on the water. Her polished oaken masts

shafted high and her white sails hung limply in a near non-existent

wind. Likely one of Prince Arnin’s scouts, mused Baus—a presence,

which, outside of the capricious wind itself proved an unnerving

coincidence, indicating the presence of freebooters troubling the

seas.

Baus turned

his gaze away. The vessels continued in their courses, moving like

sluggish turtles confined to a grievous march across a trackless

waste.

A week passed

and he stood rooted in the same spot, staring out over the ocean.

How many days had passed? Without anything significant happening in

his life? Eking out this existence on the wearisome mud flats was a

tedium beyond measure. Was he really living? He scratched his

stubbly cheek and realized that there was no more time for waiting

. . .

A distant

clank of metal issued from a stone’s throw away. Following came the

faint trickle of laughter and a call of an ekloon dipping in the

wind.

Baus peered,

perked up ears, and saw past the crumbling sea wall a score of men

stretching tarps along the communal flats. Tepee-like canopies were

being hoisted upon sturdy poles. Why were they so animated at this

early hour?

Uncertainty

changed to understanding. The fall fair was in play!

Baus trooped

back along the beach, surprised that he had forgotten. The

pencil-gaunt shapes of Harky and Nillard caught his eye. They

struggled awkwardly in the shallows, wresting a substantial wrack

of tangled nets from the brine and heaving them over their

shoulders.

Baus gave the

pair wide berth, knowing it was unwise to alert them to his

truancy.

He manoeuvred

closer to the pier and the mud flats stretched out to the water’s

edge where sounds of activity grew louder and more insistent. A

sandier strip of beach graced the bluff’s toes further inland.

Baus strode

on, arriving at a pillbox-shaped shelter of ill-fitted yew which

rose out of the sand like a sore wound. A lurid sign was pasted

above a copper goat’s bell and a club, reading ‘B-E-A-C-H

M-O-N-I-T-O-R’. The individual who manned the booth was of no great

stature. He sat on a high stool, wearing a mauve and black

pin-striped uniform. He wore his hair straight and simple, stiff as

rope, plastered to both sides of his head. A leather cord,

outfitted with black pearls and gull feathers, was wrapped about

his neck. Neither humble nor extravagant, this youth sported a pair

of squirrelly ears, a flattened nose, moon-grey eyes and a

disagreeable overbite which fixed his expression into a perpetual

grin.

Baus forced

out a greeting. Here was Weavil—town poet, laureate of odes, also

known as ‘beach monitor’. He whittled a limb of sea-beech with

innocent absorption. At his side clumped a tangle of nets and a

basket of sharp stakes, the product of his labours. In his spare

time, the poet was obliged to weave nets and whittle stakes for the

weirs, which at present were failing.

Baus tipped

his head in a formal salute.

The poet made

similar motions. “And where be we off to in such a mood of

peccadillo, Baus? Tormenting limpets and cockles as usual?” His

tone was phrased with a lofty courtesy.

“My greatest

bondage,” replied the fisherman. “And you? Still on guard for

Vrang, our elusive sea drake?”

“Never a

sign!” admitted Weavil. Mock unhappiness seemed to trace a

mischievous crinkle on his sea-lined face. “Though the legend says

the monster will fly, crimson, mighty-scaled, one day past the

Wistish Isles beyond the rim of the world!”

Baus made a

sardonic retort. “Bah! I shouldn’t be giving energy to this legend,

Weavil, or holding my breath for any drakes.”

“And who makes

you the expert?” Weavil croaked. “Are they all monkey-tales? A duty

’tis a duty.” He cocked his head to one side and seemed more a

weasel poking its neck out of a hole than a man. “I wonder about

your wisdom . . . you still have not answered my question.”

Baus

flourished impatiently. “I journey to Heagram’s fair—to reckon what

is to be reckoned.”

“A plan of

providence!” The poet jumped down from his perch. He crowded his

companion with eager enthusiasm. “Perhaps I shall taste the annual

festivities too.” He smoothed out his pin-striped vest and

straightened up taller in his seat. “Not on this instant though, as

I am engaged in ‘shore duty’, upon which I must wholly focus.”

“A sensible

plan,” declared Baus. “It is unthinkable to dip in the waters of

the Flam while on duty.”

Weavil gave an

admonitory grunt. “The razor clam and dogtooth fern surely slice

the flesh and sting the bones. You know well that Prefect Barth has

instructed me to monitor all people who approach the water. ’Tis a

known fact that my sole agency is to spy out drakes and inform the

masses of possible hazards and perils!”

“’Tis truth,

and only too evident by your modest signage. Yet my remarks remain

unaltered—I advance to the fair, and with that, I bid you good

day.” Baus sauntered off, whistling a happy note while Weavil gazed

enviously after him.

II

The port of

Heagram was populated with many folk of many qualities. It hosted a

venerable, old-style architecture rich with stone-carved fountains,

flagstoned plazas, vined archways, antique buildings and esteemed

monuments. An old bell tower stood off to the centre of

Beerstrom’s

plaza

. Curiously, a phalanx of varnished

boats and retired seacraft flanked the cool, cobbled

Sea

Alley

. Tending toward the river tumbled an array of low pilings

in the harbour, pot-darkened at their bottoms and supporting a

collection of wide wooden slats. A host of sailcraft, including the

swift two-masted

Wind Stallion

and the voluptuous

Latitude Fey

lay moored, while farther along the pier, in

somewhat murkier waters, dories and lighters lay berthed, along

with junk fishing boats, scows, cogs, paint-peeled and barnacled.

Since the beginning, Heagram harbour had been shaped in the form of

a sickle where the two rivers, the Flig and the Flam joined the

Poesasian. Now Baus saw narrow wooded peaks riding past the

conjunction of the two watercourses. Several warehouses, the

boatwright’s yard, a collection of foundries and Durgen’s

scrapyard, made themselves known, also the old gravel road,

Castaway’s Trail

, which wound its way past Muoffen’s mill

and up the Flam’s nearest foreshore. Inland past the pubs and

valestone residences loomed the grand town hall and a picturesque

schoolhouse, with freshly painted yellow roof. Behind rose ranks of

woody briar-oak, tinged with a late summer green. On top of the

bluffs the old lighthouse shone from a glassy beacon, heralding

craft from the sea.