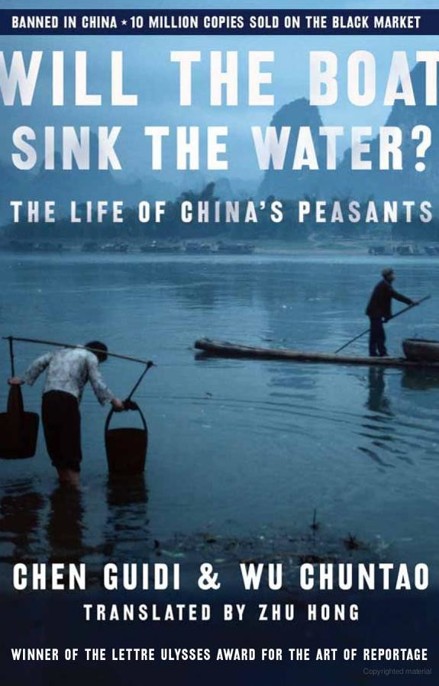

Will the Boat Sink the Water?: The Life of China's Peasants

Read Will the Boat Sink the Water?: The Life of China's Peasants Online

Authors: Chen Guidi,Wu Chuntao

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #Asia, #China, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Ideologies & Doctrines, #Communism & Socialism, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #Specific Topics, #Political Economy, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Poverty, #Specific Demographics, #Ethnic Studies, #Special Groups

WINNER OF THE LETTRE ULYSSES AWARD FOR THE ART OF REPORTAGE

will the boat sink the water

?

will the boat

sink the water

?

The Life of China’s Peasants

chen guidi and wu chuntao

translated from chinese by zhu hong

PublicAffairs

New York

Copyright © 2006 by Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao. Published in the United States by PublicAffairs™,

a member of the Perseus Books Group. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, Suite 1321, New York, NY 10107.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Chen, Guidi.

[Zhongguo nong min diao cha. English]

Will the boat sink the water?: the life of China’s peasants

/ Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao; translated by Zhu Hong.

p. cm. Includes index.

ISBN–13: 978–1–58648–358–6

ISBN–10: 1–58648–358–7

Peasantry—China. 2. China—Rural conditions. 3. Rural development—China. I. Chun, Tao. II. Title.

HD1537.C5 C47313 305.5’6330951—dc22

- 2005055344

ISBN–13: 978–1–58648–441–5 (pbk.)

ISBN–10: 1–58648–441–9 (pbk.)

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Water holds up the boat; water may also sink the boat.

Emperor Taizong (600–649, Tang Dynasty)

Author’s Preface

ixIntroduction

xviiPost-Liberation Time Line of

Events Important to Peasants

xxiiiThe Martyr 1

The Village Tyrant 27

The Long and the Short of the “Antitax Uprising” 63

The Long Road 91

A Vicious Circle 131

The Search for a Way Out 189

About the Authorsand Translator

221

Translator’s Acknowledgment

223

Index

225

In 2001, we began our work on our reportage entitled

The Life of China’s Peasants

(

Zhongguo Nongmin Diaocha

). Though we had discussed the idea for over ten years, it was when Wu was giving birth to our son in Hefei that we realized we must not put it off any longer: we witnessed a peasant woman dying in childbirth. She died because the family was too poor to afford proper medical attention during the birth.

We traveled to over fifty villages and towns throughout Anhui Province, made several trips to Beijing to talk with authorities, and interviewed thousands of peasants. All of our savings went into writing and publishing the book.

The Life of Chinese Peasants

is an exposé on the inequality and injustice forced upon the Chinese peasantry, who number about 900 million. Our book described the vicious circle that ensnares the peasants of China, where unjust taxes and arbitrary actions— or total inaction—sometimes lead to extreme violence against the peasants.

After more than three long and challenging years, our book of literary reportage,

The Life of China’s Peasants

, was completed. A shortened version—about 200,000 characters instead

author s’ preface

of 320,000—appeared in the November 2003 issue of the literary magazine

Our Times

(

Dangdai

), and the issue sold out within a week. Spreading with the speed of a prairie fire, this version appeared on websites at home and abroad. To this day, many readers still mistake it for the complete book.

One month later, in December 2003, the full version was published and distributed by the People’s Literature Publishing House. With its title plainly set down in six block characters across a yellow background, the book’s appearance was unpre-possessing, to say the least, but even so it took the Beijing Book Fair by storm, and orders for 60,000 copies were taken in just three days. The first print run of 100,000 copies was sold out within a month. For a work of nonfiction—a reportage on a subject that could hardly be considered trendy—it was a phenomenal success, even by the standards of such an established house as the People’s Literature Publishing House.

Professor Wang Damin of the Chinese Department of Anhui University described how “readers devoured it avidly, discussed it earnestly; media publicity spread like waves of the sea; literary circles were inspired to impassioned rhetoric.” Professor Damin also noted that “the corridors of power were quiet and unperturbed,” apparently registering no response to the report. We later realized that the latter observation was rash. In just one month the book sold over 150,000 copies before suddenly being taken off bookstore shelves by Chinese authorities in March 2004. After that, only pirated editions could be found on the streets, 7 million of which were sold throughout China. Meanwhile, the media response was truly unprecedented.

Producers of all the important talk shows, such as

Face to Face

,

Tell It As It Is

, the popular Spring Festival special, and other programs of China Central Television, which beams to millions of viewers, invited us to appear with them. The Central Broadcasting Company reported on the book at length during its prime-time program. Within two months, from the end of

author s’ preface

2003 to the beginning of 2004, we were interviewed by over a hundred reporters from newspapers, magazines, TV, and radio stations as well as websites from across the country. Critical articles appeared in the press and we received a cascade of letters from readers.

The publication of

The Life of China’s Peasants

has been compared to a clap of thunder. The publicity blitz following its publication has been compared to shock waves generated by the clap of thunder.

We were totally taken by surprise by this level of public attention. We had assumed that the onslaught of commercialism would mean that works of literature could no longer impact society to any significant extent, not to mention cause a sensa-tion. Of course our book was not exactly “literary” in the strict sense of the word. The deputy editor of the

Beijing Evening News

, Mr. Yan Liqiang, summed up

The Life of China’s Peasants

tactfully, saying, “The fact is, when writing on this subject, no one . . . can be simultaneously literary and analyti-cal. It is a feat to . . . master this weighty, complex, and sensi-tive material to the extent that [the authors] did. The text abounds with signs of [their] struggle to come to grips with the subject matter.”

The impact of

The Life of the Chinese Peasants

on mainland China is due not to its literary value but to the fact that it has brought out the stark reality of rural China. It has taken on a complex of problems that is generally referred to as the Triple-Agri (

San-Nong

): the problem of agriculture, the problem of the rural areas, and the problem of the peasant.

In the last analysis, the Triple-Agri is nothing less than the problem of China. Not exclusively an agricultural issue nor an economic one, it is the greatest problem facing the ruling party of China today. The problem is staring us in the face. But over the years, all we got from the media were glowing reports of “happily ever after.” City people know as much about the peas—

author s’ preface

ants as they know about the man in the moon. The impact of our book came from telling the plain truth about the lives of China’s peasants, which inspired in readers from all walks of life not only shock but also heartfelt empathy with the dispossessed.