Who Owns the Future? (22 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

What you actually get.

The overwhelming practical issue is that when you have millions of “shower knobs,” you can’t readily calculate the ideal positions for them all. A landscape can sometimes be too complicated to evaluate comprehensively.

*

You can only make progress by starting at one point on the landscape and then tweaking inputs incrementally to see if the goal you seek seems to be furthered. You crawl on the landscape instead of leaping. In other words, your best bet is to move shower knobs a little bit at a time to see if you like the result better. You can’t really explore every combination of shower knob positions in advance because that would take much too long.

*

If you had an arbitrary amount of time and computer memory to do calculations, things would be different, but even with the power of today’s cloud computers, we are unable to perform many calculations that we might like to.

This is also how evolution works. Evolution is dealing with many billions of “knobs” in genomes. If some new genetic variation reproduces a little more, it gets emphasized. The process is incremental, because there isn’t an alternative when the landscape gets extremely big and complicated.

Usually a landscape is imagined so that the solution sought would be the highest point on it. The eternal frustration is that incremental exploration might lead up to a nice high peak, but an even higher peak might exist across a valley. Evolution takes place in millions of species at once, so there are millions of explorations of the peaks and valleys. This is one reason why biodiversity is so

important. Biodiversity helps evolution be a broader explorer of the gigantic hidden landscape of the potential of life.

Markets as Landscapes

The idea of a marketplace is similar to evolution, though in the relatively diminutive domain of human affairs. A multitude of businesses coexist in a market, each like a species, or a mountaineer on an imaginary landscape, each trying different routes. Increasing the number and eccentricities of mountaineers also increases the chances of finding higher peaks that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

The reason a diverse collection of competitive players in a market can achieve more than a single global player, like a central planning committee, is that they not only have different information to work with, but also different natures. This is why a genuine diversity of players explores a wider range of options than any one global player can, even if that one player has raided all the others of their private information.

Cloud software runs on massive assemblies of parallel computers, so it can perform many incremental explorations of a simulated landscape at one time. Even so, there is no guarantee of finding the highest point, even in a simulated landscape. The variations that make different players in a market importantly different aren’t fully expressible within a single Siren Server.

A crowd of mountaineers who are all using the same guidebook will tend to swarm together and discover less overall. An occasional mountaineer ought to veer off on some strange path.

If you believe that artificial intelligence is already as creative as real human minds imbedded in real human lives, then you’ll also believe that AI algorithms can be relied on to be the most creative mountaineers, and to find the highest peaks. However, that is not so. There is no way an Amazon pricing bot will have creative ideas about how to price an item. Instead it will just enact a deadly dull price war. All bots do is use the illusion of AI to reinforce positions of network power, by taking gross automated actions like setting prices to zero. Siren Servers reduce the diversity of explorations, no

matter how big a calculation they run, thus increasing the chances that better peaks in the landscape will remain undiscovered.

Experimentalism and Popular Perception

In classical economics, a lot of attention is paid to how markets seek “equilibrium,” which is another form of peak on a mathematical landscape. In the most recent forms of networked economics, it’s clearer than ever that there’s no way to know if a particular equilibrium is particularly distinguished or desirable relative to others that might be found. There could be a great many undiscovered, but preferable equilibriums.

*

*

As the financial crises of the early 21st century unfolded, there was a fashion to invite mathematicians, computer scientists, and physicists to meetings with economists to see if any new ideas might come out. The physicist Lee Smolin published an interesting paper about multiple equilibriums as a result of some of these meetings:

http://arxiv.org/abs/0902.4274

.

The existence of multiple equilibriums is part of what’s so galling about the way networks have taken over money. Let’s suppose there’s a Siren Server making a lot of money. Maybe it’s playing little games with microfluctuations in a massive number of signals. Or maybe it’s playing a highly leveraged, bundled, remote hedging game, or a high-frequency game. Assume the scheme is working well, and the owners are doing so well that they are sure they’ve unlocked the key to the universe.

There are two common schools of thought about this sort of thing, and they are both wrong. One holds that if the money is being accumulated by these schemes, it is being taken from innocent ordinary people and impoverishing them. The other wrong school holds that optimization of a financial scheme that creates wealth for anyone anywhere also inevitably helps the whole economy, through trickle-down and the expansion of entrepreneurial avenues. These ideas, the “liberal” and “conservative” takes on wealth concentration over a network, are both based on the fallacious assumption that there’s only one way these schemes could be made to work.

In fact, all these sorts of schemes might work just as well finding

different

equilibriums. The either/or logic that pervades debates about economics should never be taken as a complete presentation of what is possible. For instance, it is entirely possible that a similar scheme to whatever cloud fund we might imagine could

also

increase employment

without

making less money. Cutting-edge entrepreneurs who have enjoyed the benefits of Siren Servers suddenly turn into backward, zero-sum thinkers when social issues are raised. If an economy can be made to employ people at all, it can probably be made to employ people without killing somebody’s precious derivatives fund.

In fact, conservatives have gone to endless lengths for decades to make this very point when it suits them. Since the Reagan era, a highlight of the conservative playbook has been to claim that lowering taxes raises tax revenues. Their claim is that lower taxes stimulate business growth independently of any other variables. That is precisely a claim that there can be more than one equilibrium.

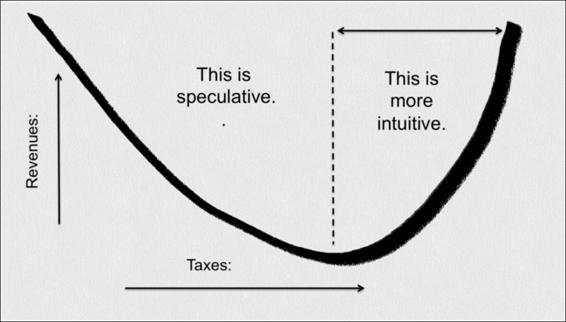

This is the famous Laffer curve, which was promoted by one late 20th century president, Ronald Reagan, and ridiculed by another, George H. W. Bush, as “voodoo economics.”

It’s counterintuitive, no? On the face of it, lowering taxes should lower the amount of money brought in by taxes. A remarkable, decades-long, and maniacal public relations campaign has brought about a general atmosphere in which the idea is respectable.

While there are huge problems with the way the idea is understood and the way it has influenced policy, the ascendance of a nonlinear,

systemic sensibility into popular folklore bodes well. If the public can “get” the Laffer curve, then the public can probably also gain a more honest and balanced sensibility of the nonlinear nature of the big challenges we face.

A serious attempt to find a Laffer peak, a long-term lower tax rate with higher revenues,

*

would have to be as experimental and long term as the quest to improve weather predictions. Maybe something about education levels, retirement rules, or even the weather would make all the difference. It would be as ridiculous to say a Lafferesque solution is impossible as it would be to say it is automatic or easy to find.

*

There have been claims that the effect has already occurred briefly in special circumstances.

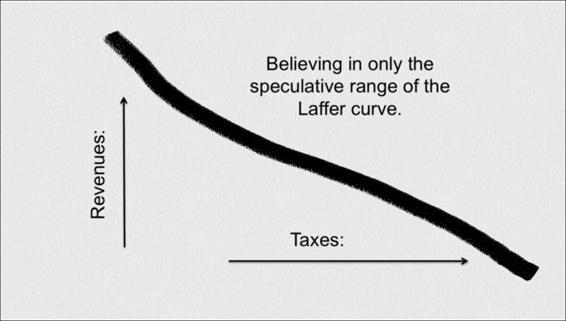

The Laffer curve was supplanted in early 21st century conservative economic rhetoric by a different curve, which is really just a straight line:

Both curves are hopelessly oversimplified. Recall your finicky shower knobs. If even your shower behaves in a complex way, surely the economy is also complex. Understanding it is more like the process of predicting the weather or improving medicine than it is like these smooth lines. Economics is a real-world big data problem, which means it’s hard. It’s not a phony big data problem of the kind being used to build instant business empires. That confusion is one of the great confusions of our historical moment.

The original Laffer curve had the merit of showing two peaks on either side of its valley. That betrayed an acknowledgment that there can be multiple equilibriums. The latest replacement, the absolute faith in austerity, doesn’t even acknowledge that. To accept it is to be completely hypnotized by the illusions of easy complexity.

It is senseless to speak in the abstract about whether the Laffer curve is true or false. It is a hypothesis about peaks and valleys on a landscape of real-world possibilities, and these might or might not exist. However, the possibility of existence does not mean that any such landmarks have been found.

Systems with a lot of peaks must also have a lot of valleys between the peaks. When you hypothesize better solutions to today’s way of dealing with complex problems, you are automatically also hypothesizing a lot of new ways to fail. So yes, there might well be ways to lower taxes that cause tax revenues to rise, or the economy to grow, but they will be tweaky and nontrivial to find.

To find that kind of sweet spot on the landscape requires a methodical search, which implies a certain kind of governmental actor, which is not to the liking of many of the people who most want taxes lowered. A government has to act like a scientist. Policy must be tweaked experimentally in order to “crawl on the landscape.” That means a lot of analysis and testing, and no preconception of how long it will take to get to a solution—or expectation of a perfect solution. Anyone offering automatic detailed foreknowledge of a genuinely complex system is not on the level. Cloud calculations are never guaranteed or automatic. It’s hard magic.

Keynes Considered as a Big Data Pioneer

The same argument that applies to taxation can just as well apply to employment. Keynes was offended by the sort of situation that can come up: People want to work, but there are no jobs. Builders want to build homes, but the customers are broke. Companies hold on to cash. Banks don’t lend. Homelessness rises as construction workers can’t find jobs. It would seem that all the necessary buyers, sellers, and financiers are waiting in the wings, and yet they fail to

interact to cause a market to rise. This is the sort of stuck state that Keynes suggested should be prodded with stimulus.

Depressions and recessions can be understood as low hills on the energy landscape of an economy. If you have made it to the top of a low hill and you crawl around incrementally, you will always lose altitude. You seem to have already found the best state you will ever find. That is what a stuck state feels like. Holding on to money is better than lending it when the borrower is unemployed.

However, there might be a much higher hill to be climbed, just over a valley. An employed borrower could get the loan to buy the house from the developer who would employ the borrower. Keynesian stimulus is supposed to function as a kick that imparts enough momentum to bound across the valley up to a higher peak.

Keynes was an unapologetic financial elitist and had no interest in a quest for income equality or a planned economy. He simply sought a mechanism to get stuck markets unstuck. No one has proposed an alternative to his idea of a stimulus. The enduring nuisance is that someone has to guess about exactly how and when to aim a stimulus kick; this is just another way of saying you can’t have science without scientists.