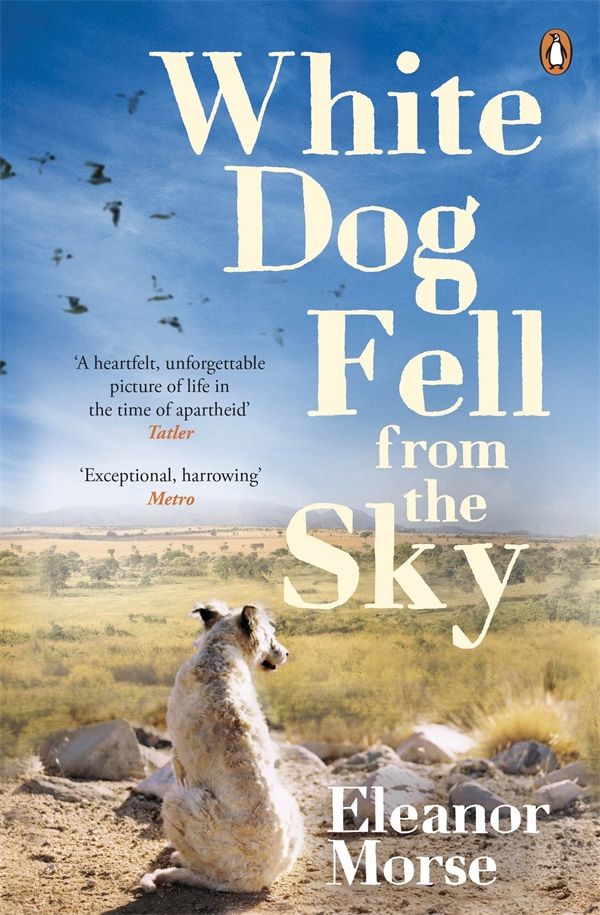

White Dog Fell From the Sky

Read White Dog Fell From the Sky Online

Authors: Eleanor Morse

White Dog Fell from the Sky

FIG TREE

FIG TREE

an imprint of

PENGUIN

BOOKS

WHITE DOG FELL FROM THE SKY

Eleanor Morse has taught in adult education

programmes, in prisons and in university systems, both in Maine and in southern Africa.

She currently works as an adjunct faculty member with Spalding University’s MFA

writing programme in Louisville, Kentucky. She lives on Peaks Island, Maine.

for Catherine & Alan

I have walked through many lives,

some of them my own,

and I am not who I was …

—Stanley Kunitz, “The Layers”

The hearse pulled onto a scrubby track,

traveled several hundred feet, and stopped. The passenger door opened, followed by the

driver’s door. Two men stepped out. They walked to the rear door, and together the

men slid out a coffin and laid it carefully on the ground. They returned to the car,

struggled with something inside, and dragged out a limp body. It was so covered with

road dust, its face was gone.

The driver splashed a bucket of water over

it, nudged it with a toe. Rivulets ran down the side of one cheek, water etching through

dust to walnut-colored skin.

“He’s late, no more in this

world,” the passenger said.

The eyelids fluttered, and the driver said,

“See, you are wrong.” They stood a moment and watched the man on the ground.

Then they loaded the coffin back into the hearse and fled. There would be trouble when

the man came to. Or if he didn’t, there would also be trouble.

The sun was risen above the first line of

scrub when Isaac opened an eye. The light hurt. The hearse was gone, and with it the

small cardboard suitcase his brother Nthusi had given him. A wind blew close to the

ground, kicking up a fine dust, covering over the tracks. The dust would cover him too,

he thought without interest, if he lay there long enough.

A thin white dog sat next to him, like a

ghost. It frightened him when he turned his head and saw her. He was not expecting a

dog, especially not a dog of that sort. Normally he would have chased a strange dog

away. But there was no strength in his body. He could only lie on the ground. I am

already dead, he thought, and this is my

companion. When you die, you

are given a brother or a sister for your journey, and this creature is white so it can

be seen in the land of the dead. The white dog’s nose pointed away from him. From

time to time, her eyes looked sideways in his direction and looked away. Her ears were

back, her paws folded one over the other. She was a stately dog, a proper-acting

dog.

A cigarette wrapper tumbled across the

ground, stopped a moment, and blew on. A cream soda can lay under a stunted acacia, its

orange label faded almost to white. Seeing those things, he thought, I am not dead. You

would not be finding trash in the realm of the dead.

He heard a voice nearby, a woman calling to

a child, scolding. He sat up. No part of his body was unbruised. Which country was he

in? Had he made it over the border?

He called to the woman, but she didn’t

appear to hear him. She stood with a child near a makeshift dwelling made of cardboard,

propped up with a couple of wooden posts, with a roof of rusted iron and blue plastic

sheeting. She gripped her child tight around his upper arm, and with the other hand

splashed water from a large coffee tin. Her boy struggled and broke free, running so

fast that tiny droplets of water fell out behind him. “Moemedi!” she

cried.

“

Dumela, mma,

” Isaac

said in greeting, getting to his feet and wobbling toward her.

She eyed him. Clouds of dust rose as he

struck his pants with his hands. “Where am I? Which country am I in?”

She didn’t answer.

He stood silently, and then said,

“Please,

mma,

am I in Botswana?”

“

Ee, rra

.” Yes,

sir.

His palm traveled down the length of his

face, as though opening a curtain. His eyes filled with relief and with the fear of the

kilometers between him and his mother and brothers and sisters and all he’d known

and understood and embraced and finally escaped.

The woman must have seen the boy inside the

man, lost like a young goat in the desert. “Where is your mother?” she

asked.

“Pretoria.”

“Your father?”

“Johannesburg.”

“What are you doing here?”

He was unable to speak.

“Do you want tea?”

“

Ee, mma.

” He took a

step toward her and fell backward onto the dog. As he was going down, his eye caught the

soda can in the bushes. The sky had been blue, the dog white, but now the dog was blue

and the sky white.

“You are drunk.”

“No,

mma,

I’ve had

nothing to drink.”

“My husband is a jealous man. You

cannot stay here,” she said. Her body was already bent, even though her boy was

young, running, running with his friends among thorns and discarded tin cans. She

disappeared into the cardboard shack while Isaac sat on the ground with the white dog.

Long ago before he’d gone to school, he remembered his mother telling him that

there were oceans on Earth. She said that the water was so big, you could not see to the

land on the other side. She’d heard that the water threads connected to the moon,

so when the moon grew larger, the waters also grew larger, like an older brother sharing

food with a younger brother. But she didn’t know where the big water came from and

went back to. Maybe to the center of the Earth, she told him, where it can’t be

seen, flowing underneath. His head felt like that water, with the moon pulling on it,

the waters going back and forth.

The woman came back out of her house, with a

tin mug. She brought a small stool for him to sit on. He stretched out his hand

respectfully, right one reaching, left touching the right elbow. He bowed his head in

thanks.

She sat on a rock near him and studied his

face. “Where are you going?”

“I don’t know.”

“Are you hungry?”

“

Ee, mma.

”

She rose again and came back with a bowl of

sorghum porridge. She poured reconstituted powdered milk on it and gave him a spoon.

“Who hurt you?” she asked.

“No one.”

“Why are you not telling the

truth?”

“The journey hurt me. No one person. I

traveled out of South Africa in a compartment under a casket.”

“Surely not. But I did see a large car

travel up that track. I saw the men pull you out and throw you on the ground. When you

spoke to me, I thought if I do not speak, if I pretend I don’t see it, that thing

will return to the dead.”

He smiled.

“You did not have money for the

train?”

“The train was not possible.”

His friend Kopano passed in front of his eyes. Two men, wearing the uniform of the South

African Defense Force, walking toward a van, no hurry. The train disgorging steam beside

the platform. The conductor:

Get your dirty kaffir hands off.

It did not matter whether she believed him

or not. Now, the problem was not the journey that brought him here, but where to sleep

tonight and the night after. In the darkness, it is said that you must hold on to one

another by the robe. But where was the robe? He would need to leave here. He would thank

this woman and be gone.

“What is this place called?” he

asked the woman. Makeshift dwellings stretched as far as you could see.

“Naledi.”

From what can you not make a house? Oil

drums, grass, mud, sheets of torn plastic, tires, wooden vegetable crates, banged-up

doors ripped from cars and trucks. Each place was called home by someone, maybe ten

people, sleeping side by side on the floor, crawling out in daylight, when the sun is

drying the blades of short grass that the goats have not yet eaten, drying the leaves of

the acacia trees with its heat. For a few moments only, this Naledi would be wreathed in

morning mist. Would he be here tomorrow to see it? He put his hand out without thinking

and touched the fur of the dog.

“When did you come here?” he

asked the woman.

“It doesn’t matter when I came. The

government says they are going to knock down all the houses.”

“What will you do then?”

“

Ga ke itse.

” She

shrugged. I don’t know. “They’ll bring the bulldozers and knock the

houses down, and then the people will come back and build the houses again.” She

looked as though he should know these things. He watched her as she disappeared around

the other side of the house.

Outside Pretoria, where he’d lived,

the police came after the sun had set. You could hear people crying that they were

coming. In the darkness they ran. They jumped over fences and disappeared into the

night. There were no maps for where they went. They rose from their beds and climbed out

their windows, and each moment was a place they didn’t know and had never been.

With the sound of the police vans, thousands departed under the rags of darkness. His

mother didn’t have legal papers. She barricaded the door and hid under the bed and

told the children to be as still as stones. But the baby cried and the police knocked

the door down and they put his mother in prison for seventeen days. When she was gone,

there was no food except grass and stolen mealie meal. Their stomachs heaved and

sorrowed with emptiness. The bitter heart eats its owner, his mother said when she

returned. He didn’t know whether she was telling him that her heart had been

eaten, or that he must be careful not to let himself be eaten. After that, she sent her

young children, all but the baby, to live with her mother in the place the whites called

the homeland, which was nobody’s homeland, only a desolate place no one else

wanted. His mother had to stay in Pretoria, where there was work for her. She’d

told Isaac, as the second oldest, that he was not to cry for her, but sometimes when she

was gone and the wind had blown across the empty ground and drowned the sounds of the

night, he couldn’t help the feelings that rose in his throat and spilled out of

his eyes.