While the World Watched (20 page)

Read While the World Watched Online

Authors: Carolyn McKinstry

Tags: #RELIGION / Christian Life / Social Issues, #HISTORY / Social History, #BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs

My dear Friend:

You have come into the fellowship of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. I am very glad to have you here with us. Your presence means much to the Church, and the Church means much to you.

The church building and equipment and even the spirit of the whole program are inherited possessions of ours. This is our church, but it cost something. The spirit of love cost Jesus his life. This is the spirit which keeps the Church alive, and assures its triumph.

I paused from reading and looked at the church’s cracked walls and wet carpet.

What will it cost us,

I wondered,

to repair this church and keep it going?

Jesus paid it all, that the atmosphere of higher things might be breathed by every living man. Buildings and equipment cost the men and women of the past and present no little effort. The Ministers and people of the past are glad to hand to us this “Our Sixteenth Street.” They were mindful of us.

I thought about all the people who had sacrificed time, money, and energy to build the grand old church and to furnish it with everything they needed to worship God as a community.

We must be mindful of the present and coming generations. To do this in the right way, we must make a full and rounded effort to offer to God and the future, a better Sixteenth Street.

The pastor then made a written appeal to his new member:

You are urged to help in this. The way is simple: Consecrate your life to God. Attend the services of your Church, especially the prayer services. Be loyal to your God; your Church, and its program. Be liberal in your giving, realizing that the future generation must inherit great things, that they might know how close we lived to God. Don’t forget to pray for your Church’s success, and for the blessings of God to be ever upon your Minister.

Yours in His Name,

C. L. Fisher

“Dear Lord!” I said when I finished reading. It was as if Pastor Fisher had written this letter specifically to me! Surely what had been true for Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1926 was still true in 2002!

God spoke clearly to me through the pastor’s yellowed letter.

“Lord,” I prayed, “through Pastor Fisher’s appeal, are you showing me the more important work you want me to do for you, for your people, and for your Kingdom?”

Yes, child,

he spoke to my heart.

I put the letter down. “But, Lord,” I asked, “how can we repair the church and make it better for future generations if we have no money?”

You can raise the money, Carolyn,

God said to my spirit.

Me? Raise the money? “It will take millions of dollars to repair this church, Lord! I have no idea how to raise that kind of money!”

God sent to me, and to our church, a huge blessing in the form of Dr. Neal Berte, a retired president of Birmingham-Southern College. I expressed to him my vision for the church and the needs I saw, and he helped me start a campaign in Birmingham to raise the money. He encouraged me and taught me how to approach people around our city and state and ask for their help. In my view, this wasn’t just a reconstruction campaign; it was part of the bigger vision for reconciliation in our city. I felt that God was calling me to be part of this effort to bring people together, to demonstrate a tangible expression of interracial progress.

It seemed that everyone I talked with wanted to donate money to the cause—individuals, corporations, and foundations. In a relatively short time, they contributed almost $4 million! In my eyes, one of the biggest blessings was that the campaign crossed all socioeconomic, religious, political, racial, gender, and age boundaries. Many donors had never had the opportunity to make a public statement for Civil Rights. They considered this fund-raising campaign an opportunity to do so.

With $4 million in the Sixteenth Street Foundation Inc. treasury, I told Jerome, “Now there will always be resources to maintain Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, to keep it alive, to keep telling the story.”

The foundation hired architects and construction crews to complete the extensive renovations. In the midst of the repairs, the architect posted a sign at the church—a statement that perhaps said it all: “A restoration of hope!” Dr. Berte later told the

Birmingham News

, “We weren’t sure we could get the money. I think it’s a tremendous testimony to Birmingham—it speaks volumes about how far our city has come.”

[84]

When I stepped back and looked at the newly restored church, it truly felt like a piece of God’s work of redemption. The place that had once been the site of lives lost was once again a place of new life. The place that had been a marker of hatred and despair was now a symbol of hope and reconciliation. The history and legacy of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church would be forever visible—a tall, stately sign of struggle, sacrifice, and triumph.

But our work was not finished. Now that the outer structure was once again secure, Dr. Berte and I wondered whether the church, with its rich history and its role in the Civil Rights movement, should be listed as a national historic landmark. That would qualify it to receive federal funds so it would remain strong, stable, and safe for future generations. Through the untiring efforts of Marjorie White, president of the Birmingham Historical Society, the church earned the national historic landmark status. It fell to me to fly to Washington, D.C., to address the United States Department of the Interior Committee on National Historic Landmarks. I told them the church’s story and why we thought the church should be considered for this national status. I recounted the details of the church bombing, recalling that September morning somberly.

The committee listened. And they agreed. In 2006, Sixteenth Street Baptist Church became a national historic landmark. The United States attorney general, Alberto Gonzales, brought the landmark paperwork and plaque to the church himself.

* * *

Every day, 365 days a year, people come from all over the world to visit Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. They want to see the place and touch the building where courageous people died in the struggle for freedom. The church remains a symbol of hope for all who enter its doors. The church does have a history marred by pain and loss, but it has also inherited a legacy of hope, love, and reconciliation.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “I like to believe that the negative extremes of Birmingham’s past will resolve into the positive and utopian extreme of her future; that the sins of a dark yesterday will be redeemed in the achievements of a bright tomorrow.”

[85]

God is capable of redeeming even the ugliest and darkest moments from our past. But sometimes we first have to be willing to go back and face some of those painful places again. For example, if I’d had my way, I would never have set foot in Princeton Hospital again. But in the roundabout way in which God often works, I did find myself back there . . . some forty years after Mama Lessie’s death and thirty years after Grandaddy had died there.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, I was getting my seminary degree at Birmingham’s Beeson Divinity School on the campus of Samford University—something I wouldn’t have been able to do just a generation ago. During the course of my master of divinity classes, I journeyed back to Princeton Hospital for an internship. It was something my soul insisted I do. I had “unfinished business” there, and I needed to deal with it head-on. This time, however, I visited not as the little girl in the corner of the basement when Mama Lessie had died but as a hospital chaplain.

The hospital had long been desegregated by this point. In my rounds as a part-time chaplain, I often thought back to those sad, frightening days when Mama Lessie lay dying in the unfinished basement. Now, as one of God’s servants, I could provide spiritual and tangible comfort to those who needed it, without regard to color or religion. I could offer love and support during their times of illness and bereavement because I knew what it was like to be there. In his divine knack for bringing things full circle, God called me to do for others what had not been done for my grandmother.

* * *

The deaths of my four girlfriends left me with a pain I cannot describe. But something beautiful has come of it, and that’s the vision God has given for reconciliation. My passion is to see people learn to work together and appreciate the diversity God created among us. This has become a calling for me, and I think about it all the time. I have been given opportunities to answer this call in my own city in smaller, daily ways. But I also receive national and international invitations to share that same passion for reconciliation in our world.

In the 1960s, it seemed as though reconciliation was primarily about blacks and whites. But today it’s even broader, and it really comes down to interactions between individuals. The core of the issue is still the same, however. I believe that if we can’t learn to live with our brothers and sisters here on earth, how will we get a chance to work it out in heaven? I also believe that one good deed begets another good deed and that if we all adopt a spirit of love toward our neighbors and toward each individual we encounter, we can slowly make this world a better place—a place of reconciliation, as God intended.

It has been more than forty years since my friends were killed, and we’ve made some progress in that time. But I have a greater vision for the next forty years—a vision of building a society where the lamb can truly lie with the lion and there will be peace.

I’m reminded of one of the classic hymns we used to sing at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church: “It Is Well with My Soul.”

When peace, like a river, attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou has taught me to say,

It is well, it is well, with my soul. . . .

And Lord, haste the day when my faith shall be sight,

The clouds be rolled back as a scroll;

The trump shall resound, and the Lord shall descend,

Even so, it is well with my soul.

At this point in my life, I am able to imagine Addie, Cynthia, Denise, and Carole perched on a cloud somewhere in the sky, their arms around each other, looking down at the church. And it is clear to them that all is well. They are waving their hands and saying, “Carry on! Carry on! It is well with our souls.”

And it is also well with my own soul.

Photo Insert

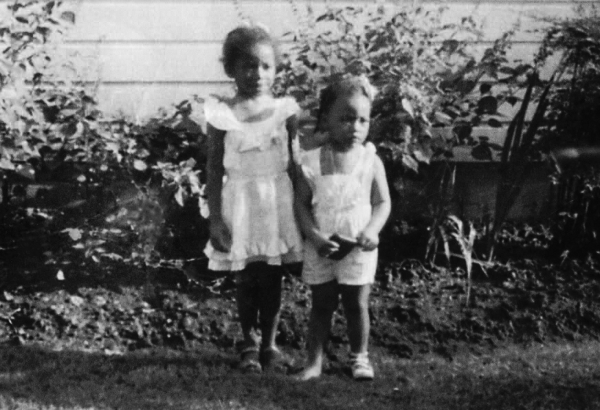

Me at age two with my aunt Maxine in front of our house in Birmingham.

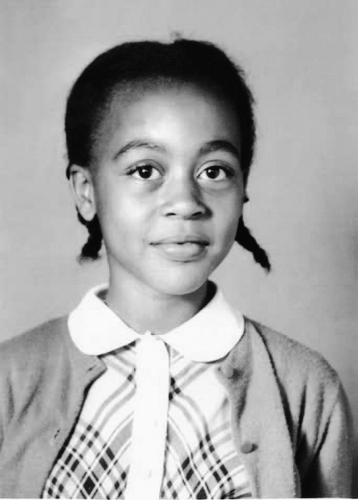

Me at age nine in my third-grade school photo.

Me at age two (on the right, with one shoe), playing with friends in our front yard.

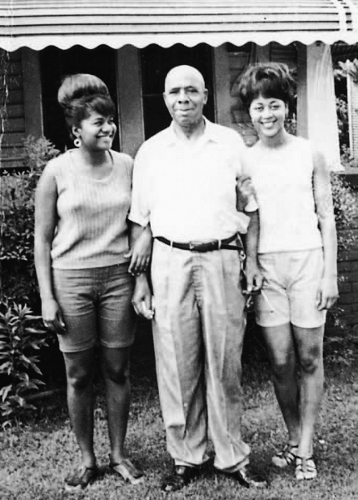

Standing in front of my granddaddy’s house at age thirteen with my cousin Deloris (on the left) and my granddad, Rev. E. W. Burt.

Taken on my graduation day from A. H. Parker High School, May 1965.

Me during my freshman year at Fisk University.

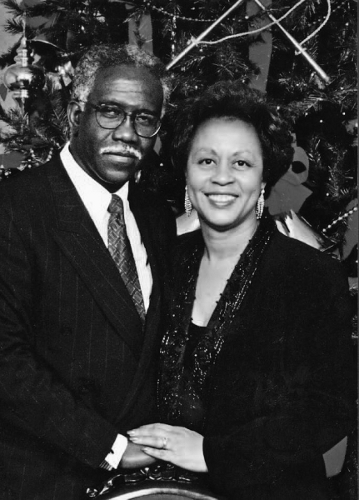

With my husband, Jerome, on Christmas Day 2002.

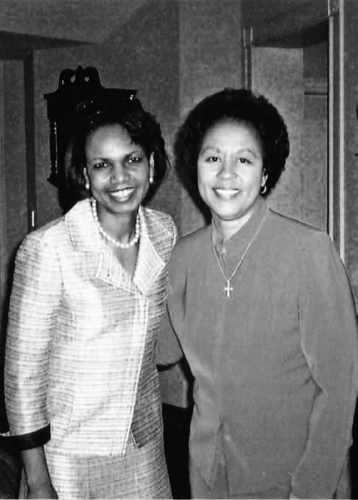

With Condoleezza Rice at an event in Duluth, Georgia, in April 2008.

With Jimmy Carter at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in January 2009.

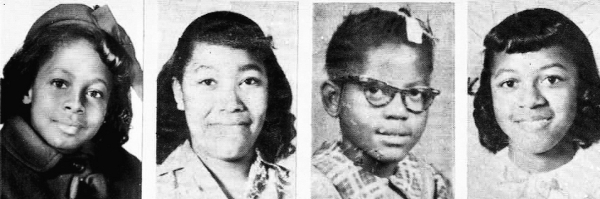

I lost my friends (from left) Denise McNair, 11; Carole Robertson, 14; Addie Mae Collins, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14, at 10:22 a.m., September 15, 1963.

A civil defense worker and firefighters walk through the debris following the explosion at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

Police officers stand guard outside the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church after the bombing. The explosion did extensive damage to the church and shattered the face of Jesus in the stained-glass window seen in the background.

Flowers cover the caskets of Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, and Cynthia Wesley as funeral services are held at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church on September 18, 1963.