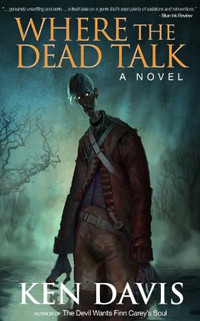

Where the Dead Talk

Read Where the Dead Talk Online

Authors: Ken Davis

Where the Dead Talk

By Ken Davis

First Kindle Edition

Copyright 2011 Ken Davis

Cover art by Mike Bear

Kindle Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Amazon.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

For Lisa and Lila, always and forever.

April 23, 1775, West Bradhill, Massachusetts

A Terrible Thing

It was a terrible thing they were doing, he knew that much. Thomas Chase didn't know why they'd brought him along, or what they planned on doing with his dead cousin Nathan out by the old lake. He supposed his uncle Joseph was mad with grief – but that didn't explain why father wasn’t doing anything to stop him. They left him with his questions to watch the horses, and that was fine with Thomas. It was past midnight and a deep chill held the woods. His breath hung in rolling clouds; steam rose off the horses' backs. He didn’t know these woods well, being so far out from the village, out in the lonely stretches that folks stayed away from. He didn’t like them, either – they were dark and still, with old trees close together. Even so, he was glad not to have to see what was going on at the water’s edge.

A cold half an hour passed before a hand fell on his shoulder. Thomas started and spun around. It was his father, face grim. He motioned and Thomas followed, pushing through branches and thickets until the trees opened up on the lake.

The body was gone.

At the edge, moss-patched granite overhung the water. Moonlight shimmered on the water's surface some dozen feet below. His uncle grabbed his shoulder. Thomas flinched and looked up into his wide eyes and twitching mouth. Joseph shook him by the front of his cloak and pointed to the water. Thomas tried to pull away.

"Told you he couldn’t do it," Joseph said. His breath was sour.

"He’ll understand," Samuel said, "He just can’t see your lips."

"This’s why I didn’t want him here in the first place, he's useless. Just have him do it," Joseph said. He shoved Thomas towards his father.

"You can’t do this," Samuel said. "Leaving him out here won’t make it go away – you know that. Of all people."

"Meaning what?"

When his father had nothing to say to that, his uncle leveled a pale finger at him.

"You don't stop now," he said.

Samuel stared at him for a long minute, then stepped over and put a comforting hand on Thomas’s face, turning his head towards the water again.

"Right there," he said.

His father pointed to a spot above the water. At first, it looked like just another gray outcrop of rocks and moss. Then Thomas realized that it was the body. Bent saplings and broken plants marked where it had slid down the face of the rocks toward the black water. It hadn’t made it all the way – it was caught up on a thick root.

His cousin Nathan.

Looking at the body made Thomas want to run back into the woods – he couldn’t swim and didn’t like heights, and the thought of having to touch his dead cousin was enough to twist his stomach. Still, he was tired of everyone thinking of him as useless. He stepped forward and began picking his way down. He slid in spots, feet shifting for purchase, hands grabbing what they could. Saplings and mossy fissures in the rock allowed him to work his way down the steep drop. His hands were cold, his eyes drawn to the dark water below him. At one steep spot, he missed a foothold and nearly slid past the body into the water. Then he was next to his dead cousin. Nathan's eyes were open, dry and staring empty at the moon; his head lay at a funny angle to his shoulders. A matted patch of hair and bone on the side of his head marked where he’d smashed against the edge of the wagon – Thomas didn't look too closely at the wound.

He inched closer. A rock came loose and tumbled into the lake with a ploonk, rippling the surface. Steadying himself, he reached over and yanked on his cousin’s jersey, hoping to free the arm over the root. The material ripped. Thomas grabbed the arm instead, and shuddered at the feel of the flesh – it was like cold clay. Thomas pulled, scared and wanting to get the horrid task done with, wanting to get away from the dark lake.

The root let go from underneath the arm. The bag of stones tied to Nathan’s ankles pulled his body down to the water. Thomas lost his footing, and was suddenly sliding down next to the corpse. Terrified at the thought of plunging into the black water with Nathan, he cried out. At the very edge, his behind caught on a stone as his legs went out over the water. He looked down just in time to glimpse his cousin slipping down into the water. For a moment more, Thomas could see the hands, pale fish swimming down into the depths. Once the trickle of dirt and stones ceased, the surface of the water smoothed and the moon shown on it. A few bubbles rose from below and then all was still.

The stars to the east faded into a deep indigo as the two men and the boy came out of the woods and onto the road. Frost thatched the ground. Thomas rode the smallest horse, leading the riderless horse by the reins. His hands were sore from the cold. He wanted his own bed, where he might start to forget the long night. Joseph turned around and spoke to them. Thomas watched his lips.

"I'll not lose him, I won't. This bloody curse won’t take everything from us," his uncle said. "That's what this is. Do you understand?"

Thomas looked to his father, but Samuel kept his eyes forward. They’d argued about it the entire while on the way to the lake, and now he was past further talk. His uncle turned to him.

"And it’s not anything like before," he said, "not a single bit. This was an accident."

Thomas didn’t know what he meant; hadn’t known what they were doing in the first place, hadn’t wanted any part of it in the second.

"He's my boy," Joseph went on, "a good boy, not fit for leaving. Not yet."

The horses' shoes were quiet on the road, now and then catching a small rock with a soft clack. Sunrise was near.

"My good boy," Joseph said. He was pleading with them. Tears slid down his face. Thomas thought he should say something; instead, he looked away.

The Lake (Part One)

A day came and went, and the sky drained of color, the final light of sunset painting the tips of the trees and then fading. The dark woods stood silent. Stars came out, caught by the surface of the lake, riding still on the deep black water, smooth as marble. In the middle, a ripple broke and rode out in circles. Then another. It was nigh on midnight when something pale neared the surface.

This Isn’t Right

He sat on the fence rail, waiting, his shadow lengthening. Lamps came on in the kitchen of the farmhouse behind him as the road turned faded to a silver river in the dusk.

He’s late, Thomas thought. He’d been waiting two long days, and was fair to bursting for wanting to see his brother, to have Jonathon explain to him why they'd done it. A speck came riding towards the house, some ways up, coming from the direction of the Boston Road. The shape of a wagon pulled by a single horse came clear, even in the greys of twilight. The driver was wrapped in a cloak.

"Jonathon!" Thomas called, "Oi! Jonathon!"

He waved his arms and the gesture was returned by the driver of the wagon. Thomas sprinted towards him.

"Easy there, little man," he said. Jonathon held out his hand and lifted Thomas up onto the driver’s bench.

"Cousin Nathan’s dead," Thomas said around great breaths of cool night air.

Jonathon smiled and then looked confused.

"Nathan's what?"

"Day before yesterday. He fell from the loft swing at the mill when we were moving the powder and guns because word came that the British are coming for them, hit his head on the wagon below and broke his neck."

Jonathon stared at him, his face caught by the news.

"And we buried him that night out in the lake past the Stag Jump Brook. In the water."

His brother stared a moment longer, then looked up at the house where the lamps burned warm yellow against the dark. Jonathon whipped the reins and the wagon bounced on the road.

It fell on Thomas – naturally – to take care of the horse and wagon, so by the time he got into the house, he didn’t know what was going on. Jonathon and their father were next to the hearth in the kitchen, arguing. The embers of the fire were a muted orange. Jonathon waved his arms around, sometimes even getting up on tiptoe to make a big point. The lanterns fluttered with the breeze as Thomas closed the door. He slipped into the kitchen, to where he could see both their faces. He’d lost most of his hearing during the horrible winter when he’d been six, but he was good at reading lips – and it was easiest with Jonathon and his father.

" – but now you need me," Jonathon said.

"That’s right," his father said, "I need you. Here. It’s your responsibility."

"How can you say that? Liberty is all of our responsibility – isn’t that what the pamphlets say? What you’ve said."

"It’s not that easy."

"But we need every man," Jonathon said, "especially with Nathan not here."

"We put him in the lake," Thomas added.

His father looked at him with fury – he took two steps over and slapped Thomas hard across the cheek with the flat of his hand.

"Enough," he said. "No more of that, young master. You will never speak of that again."

Thomas stepped backwards, touching his hand to his stinging cheek, his eyes filling with tears of shock. His father had never struck him before, ever.

"Look," Jonathon said, ignoring Thomas, "our militia has been summoned and we may have only one chance to bring the fight to the King’s men. We can’t fail. We can’t – and that means that we need to all bring the fight."

"Absolutely not. You’re to stay here and watch Thomas, watch the house and shop."

"I’m sixteen –" Jonathon cut in.

"And that means nothing."

Thomas shifted.

"I’m old enough to watch myself," he said.

"No you’re not," Jonathon said – Jonathon, of all people.

"I'll go, too," Thomas said. He reached into his breeches pocket and pulled out the cracked fife he’d found a month back, outside of the press in Danvers.

"I can play with the fife and drummers," he said, "and we can all go."

"That’s all we need," Jonathon said, "a deaf fifer. Why do you always carry that broken thing around?"

Thomas pointed the fife at him and raised his voice.

"I could do it. I can still help, and shoot. I’m not afraid to shoot a Brit. And I can shoot a better musket than you – uncle Joseph said so just two weeks back."

"I let you win," Jonathon said.

"You didn’t."

He frowned and put the fife back in his pocket.

Samuel Chase took down the musket that hung over the table and began gathering his powder and cartridges, shot and other items.

"We’re gathering the men outside Brewster’s at first light," he said, "and we march from there. I have work to do."

"How long will you be gone?" Thomas said.

"Time will tell. In the meantime, you keep up with your chores and help your brother."

He turned to Jonathon, who was downtrodden.

"You need to finish off the Currier job for me. I’ve laid half the type, you do the rest. And you keep an eye on the property and if you see or hear anything strange, you find old Pannalancet, tell him about it."

"Nathan and I were supposed to go, too," Jonathon said. He turned and walked out of the kitchen. Thomas looked at their father. In the lamp light, he looked older. He motioned him over and Thomas stood before him, nervous.

"Listen to me," Samuel Chase said, "I’m sorry for hitting you, but you’re never to tell anyone else about what your uncle and I did with your cousin."

"But why did we –"

"No one, and I mean that. I know it doesn’t seem right. Maybe it’s not – but Nathan was all he had. He’s family, my brother."

Thomas still didn’t understand.

"And you forget anything else he said. That’s all gone now, and best left there. Do you understand?" his father said.

Thomas nodded his head slowly, pretending.

In their bedroom, Jonathon rolled up a shirt and stuffed it in a haversack.

"What are you doing?" Thomas said.

Jonathon waved his hand, annoyed.

"Close the door," he said.

A lantern burned on the small writing table by the window. Thomas threw the cracked fife onto his bed and stood by Jonathon – he had a pile of wrinkled apples, and a knife.