When You Dance With The Devil (Dafina Contemporary Romance)

Read When You Dance With The Devil (Dafina Contemporary Romance) Online

Authors: Gwynne Forster

BOOK: When You Dance With The Devil (Dafina Contemporary Romance)

11.86Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Also by Gwynne Forster

When the Sun Goes Down

A Change Had to Come

A Different Kind of Blues

Getting Some of Her Own

When You Dance with the Devil

Whatever It Takes

If You Walked in My Shoes

Blues from Down Deep

When Twilight Comes

Destiny’s Daughters

(with Donna Hill and

Parry “EbonySatin” Brown)

A Change Had to Come

A Different Kind of Blues

Getting Some of Her Own

When You Dance with the Devil

Whatever It Takes

If You Walked in My Shoes

Blues from Down Deep

When Twilight Comes

Destiny’s Daughters

(with Donna Hill and

Parry “EbonySatin” Brown)

Published by Kensington Publishing Corp.

When You Dance with the Devil

Gwynne Forster

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Carole K., Carol S., Chloe G., Donna H., Ingrid K., and Melissa F., who have supported and encouraged me during my decade as a published author. I cherish each of you.

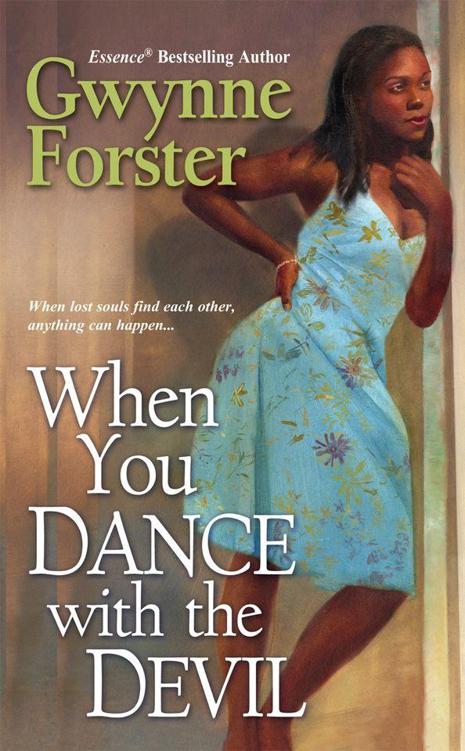

To my editor, Karen Thomas, whose helpfulness, graciousness and professionalism make my work a joy, and to Kristine V. Mills-Noble, whose wonderful cover designs for

When You Dance with the Devil

and my previous two Kensington/Dafina novels enhance their salability. I am also grateful to my husband for his unfailing support.

When You Dance with the Devil

and my previous two Kensington/Dafina novels enhance their salability. I am also grateful to my husband for his unfailing support.

As always, I thank God for the talent He has given me and for the opportunities to use it.

Chapter One

In the darkening mist of that cold December afternoon, Sara Jolene Tilman stared down at her mother, reposing peacefully amidst red and yellow carnations—flowers suggestive of joy rather than sorrow—and whispered, “Yes, Mama.” She had avoided burying her mother beneath a blanket of white flowers for, to her, white symbolized purity, and nothing—not even death—would lead her to link Emma Tilman with purity. To her mind, meanness was incompatible with purity, and meanness was the one word that, since her early childhood, she had always associated with her mother.

“Yes, Mama,” she said, almost sneering, turned away dry-eyed, and left Emma Tilman to the undertaker and grave tenders.

Sara, do this and Sara, do that. Sara, bring me this. Pick up that. Sara, come here. Sara, go there. Commands that she would never hear again, and that she would not miss.

From the little she had seen of other children with their mothers—so little because Emma did not allow her to visit other children—kindness was the least she should have received from Emma Tilman. Kindness? She pulled cold air through her teeth. If Emma had ever smiled at her, Sara Jolene had not been looking. But Emma had been adept at mental torture. She didn’t engage in abuse, at least not the kind that bruised the skin; she used her tongue to inflict the punishment.

“You’re not worth the lard that goes into the biscuits you eat,” Emma would say when Sara Jolene asked her mother for shoes or other basic necessities. “You’re useless.” She would never forget the times when, in one of her frequent rages, Emma would scream at her. “Go hide your ugly face. I wish I had never seen your daddy. I couldn’t even abort you, hard as I tried.” Maybe now, the hatred and resentment she felt for her mother would cease hammering at her head, like daylong migraines, and churning in her chest like acid reflux.

Tears? She had no tears for Emma Tilman. For five long years she had nursed and cared for her bedridden mother, and not one word of thanks, not one gesture of appreciation. But as she stumbled away from the grave, she dabbed at the brine dripping from beneath her eyelids, blinding her as she walked. The tears that finally streamed from her eyes were tears not of mourning but of relief, and tears for the dark unknown that lay ahead of her.

Sara Jolene was not afraid. The hard life she’d lived had inured her to anxiety about possible calamities. Before her mother’s seemingly interminable illness, for six terrible years she’d had the burden of caring for her stroke-bound and bed-ridden maternal grandmother, a woman every bit as domineering, mean, and lacking in feeling and warmth as Emma Tilman.

She threaded her way past tombstones and crosses, over ground hardened by Hagerstown, Maryland’s icy winter, struggling with her shoulders hunched forward until she reached the black Cadillac where her mother’s pastor detained her.

He grasped her upper arm. “I’m truly sorry, Sara Jolene. I know this has been difficult for you.”

Sorry about what? Neither he nor his parishioners had done a thing to ease the burden she’d struggled under all those years. She looked over toward the small group of people walking down the hill and raised her hand in a weak wave at the seven individuals who had cared enough to tell her mother—a woman without friends—goodbye. “I’m no worse right now, Reverend Coles, than I ever was. This is just different.”

“But you’re all alone now.”

“Wasn’t I always alone?” She attempted to move on, but he detained her.

“I know. You can make a fresh start now, if you will. Move to another town and do something with your life. If you don’t get out of that old house, you’ll waste away, a bitter woman like your mother and your grandmother.” She watched as he wrote a few lines on a card and handed it to her. “My sister has a place on the Atlantic Ocean not too far from Ocean City. You can make a living over there. Just tell her I sent you.”

She looked at the card before slipping it into her pocketbook. “Thank you, sir. I may need it.”

“Use it,” he called after her, “and be careful, now.”

Careful, huh? He didn’t have to worry about that. From now on, she was looking after number one.

She walked into the house, turned on the hall light and closed the door behind her. Maybe the preacher was right. She had no reason to remain in Hagerstown. When she hung up her coat, the cold seeped into her. She started to her room, shivering, to get a sweater and remembered that there was no one to tell her she couldn’t turn up the heat. As the room warmed, she walked through the house turning on all the lights, banishing what seemed to her like eons of darkness. Then she turned on the radio, unable to remember when she had last heard music in that house. Laughter poured out of her until, in tears, she collapsed into a dining room chair.

“Don’t you want to keep some souvenirs of your mother?” the real estate agent asked Sara Jolene three months later when she sold the house with everything in it except her clothes.

“You’d be surprised at the souvenirs I have,” she said, ignoring his quizzical expression. “I wish I could give you the memories that go along with the house.”

“Too bad. Where can I reach you if I have any problems?”

She stared at him. “What kind of problems you expecting? We just closed the deal. I got my money and that’s all I want from you.” At his expression of surprise, she added. “And my house is all you’re getting from me.”

“Why, Miss Tilman, I can’t believe we’re having this conversation.”

“Everybody knows I’m on my own for the first time, but maybe y’all don’t know that I’m not dancing to anybody’s tune but mine. When they buried mama, they threw dirt on the last person who’s going to exploit

me

. I’ve met all the conditions of sale. The house is broom clean. I had the chimneys swept, new locks put on the doors and the back steps repaired. So, mister, you don’t need to get in touch with me for a frigging thing. My business with you is finished.”

me

. I’ve met all the conditions of sale. The house is broom clean. I had the chimneys swept, new locks put on the doors and the back steps repaired. So, mister, you don’t need to get in touch with me for a frigging thing. My business with you is finished.”

If he thought her fair game, she’d show him. She knew people believed her to be timid, even cowardly, but she wasn’t; she was Emma Tilman’s unwilling victim. Not even the local sheriff stood up to her mother, and Emma got off scot-free when, in anger, she’d dashed hot water on a neighbor, leaving the woman permanently scarred.

The preacher’s car approached, and she was certain that he would continue on, wherever he started, but he parked in front of the house she’d just sold. She walked toward him.

“I just closed the sale at the bank this morning. Your sister is expecting me tomorrow, sir.”

“Yes. She called to tell me. I’m glad you decided to go there. I don’t think you’ll be sorry. God bless you.” His gaze roamed over her for a second, and then he started the engine and drove away. She wondered at his interest. He visited her mother only to bring communion once every three months, and hadn’t visited but once, for a short while, during her last days. Well, few people had seemed able to tolerate her mother’s company. And who could blame them? She quickened her steps and headed for the inn where she would spend the night and where she’d left her few belongings.

Thirty-five years and not a thing to show for them. Well, that’s all in the past. Tomorrow, I’ll start finding out what life is really like.

The following afternoon, Sara Jolene opened the back door of the taxi, went around to the trunk and unloaded her three suitcases and two shopping bags. Then, she went to the driver’s side of the taxi and gave the man sixteen dollars and eighty cents, the amount on the taxi meter.

“Don’t you people tip?” he asked, his face red with anger and his blue eyes flashing with what she didn’t doubt was scorn.

“We tip when

you

people get off your behinds and earn it,” she said, looking directly into his face, a face mottled with fury. “I’m not paying you to sit on your behind while I lug these heavy suitcases from the trunk of your taxi. Being black doesn’t mean being stupid.” Lord, how good it felt to speak her mind. She was through with “yessing” people.

you

people get off your behinds and earn it,” she said, looking directly into his face, a face mottled with fury. “I’m not paying you to sit on your behind while I lug these heavy suitcases from the trunk of your taxi. Being black doesn’t mean being stupid.” Lord, how good it felt to speak her mind. She was through with “yessing” people.

A tall, brown-skinned woman with large brown eyes, a pointed nose and pouting bottom lip, Sara Jolene wore arrogance easily, though she wouldn’t have defined her attitude as such. Her good looks had never interested her; any effort she’d made on her own behalf had been directed toward the simple matter of existing. With her mama gone, she easily found avenues for her lifelong resentment.

When the taxi driver drove off with a powerful burst of energy and speed, Sara Jolene had a feeling of immense satisfaction because she had infuriated the man. Looking up at the big white wooden structure, its green shutters gleaming as if they had all been painted that morning, and at the white rocking chairs scattered along the front porch beckoning like the “house by the side of the road,” a shiver or two shot through her body. Undaunted, she picked up the heaviest suitcase and started up the walk. The front door opened, and a stocky African-American man of about thirty rushed out to meet her.

“Afternoon, ma’am. I’m Rodger. Miss Johnson is expecting you. I’ll get your things up to your room.”

“Thank you, Rodger. You’d a thought that taxi driver would at least have taken my things out of the trunk for me.”

“No, ma’am. I wouldn’t. They take your money, but they sure don’t do much for it. You go on in. I’ll look after this.”

She wanted to ask Rodger who he was and what he did at the Thank the Lord Boarding House, but the bite of her mother’s tongue had taught her that it was best not to ask questions.

A matronly woman about five feet, six inches tall who bore no resemblance to the Reverend Philip Coles met her at the front door. “Welcome, Miss Tilman. I’m Fannie Johnson. Your room’s right at the top of the stairs, and it’s on the front. Course, if you want to face the bay, it’s fifty dollars more per month.”

She imagined Fannie Johnson’s age to be somewhere between fifty and sixty, although her prudish appearance might have added more years than she had earned.

Sara Jolene stared at the woman, wondering if she was going to like her. “I don’t have fifty dollars to throw away. I’ll take the front room.”

“Come on. After I show you your room, I’ll get you a sandwich. You must be tired and hungry after your trip. I sure hope you’re not a vegetarian. And no smoking. If you do, you’ll be responsible for cleaning your own room and bath. No liquor in public rooms, other than wine with dinner at the table, if you want it, and no bad language. No men in your bedroom, but they can visit you in the lounge, and if you want to invite a guest for dinner, it’ll cost you ten dollars. Try to get along with the other residents. We’re a happy family. If you get sick, we’ll take good care of you. Breakfast at seven-thirty, lunch at one, but let the cook know you’ll be taking it, and supper at seven. As of now, there are no roaches and no bedbugs in this house. I hope you didn’t bring any.”

What a mouth! Sara Jolene looked hard at the woman, deciding whether to be insulted and tell her off or to bide her time and see whether she wanted to stay. She did neither. “Miss Johnson, I just buried my mother. For thirty-five years, I did as she commanded. When I left her grave, I vowed never to let anybody else treat me as if I’m a child. I’d appreciate a sandwich and your apology. Thank you.”

“No point in—”

“I’m not unpacking till you apologize for that crack about the roaches and bed bugs.”

“Oh, all right. I’m a Christian woman, and I believe in peace. I apologize, and I’m glad to have you with us. Baked ham or turkey in your sandwich?”

Sara Jolene could feel her bottom lip drop. The woman could switch gears like a racing car driver. “Ham, please.”

“It’ll be on the dining room table in ten minutes.” She started from the room, turned, walked back to Sara Jolene and put an arm around her shoulder. “I’m sorry about your mother. May the Lord let her rest in peace.”

Unaccustomed to such gestures, Sara Jolene flinched at the woman’s touch. “Not a chance,” she muttered, and Fannie’s eyebrows shot up.

Then, Fannie lifted her right shoulder in a long shrug. “Well . . . uh, what do you want us to call you? We use first names. I’m Fannie.”

“My name’s Sara Jolene, but I . . . uh . . . like to be called Jolene.” She hoped she never heard the name Sara again. “This is a huge house, Fannie. How many boarders live here?”

“Ten with you, and I have one vacancy. When I’m full, there’re twelve of us living here.”

“Twelve. I hope I don’t go out of my mind.”

“You won’t. You’ll find them very friendly. The Lord put us all here together for a purpose. Just let him do his work, and you’ll be happy.”

As she watched Fannie trip down the stairs, Jolene couldn’t help wondering if the Lord was doing his work all those years when first her grandmother and then her mother abused her continuously as if doing so was their right. She doubted it. What she didn’t doubt was that, from then on, she was going to get some of her own and if that meant stepping on a few innocent toes, so be it.

She unpacked, shook out her clothes, and put them away. With pale yellow walls, white curtains and bed-spread, and two comfortable over-stuffed chairs upholstered in pale yellow, the room appealed to Jolene, especially its cheerful and sunny appearance; it was a drastic change from the house in which she spent her first thirty-five years. When she went to wash her hands, she discovered that her bathroom was also yellow and white. She hurried down to the dining room where the sandwich, a glass of iced tea and an apple rested in the middle of a place setting. She blinked back the tears. At last, somebody had done something for her.

Other books

I SHALL FIND YOU by Ony Bond

Home Song by LaVyrle Spencer

Flights of Angels by Victoria Connelly

Running the Maze by Jack Coughlin, Donald A. Davis

The War Machine: Crisis of Empire III by David Drake, Roger MacBride Allen

Palafox by Chevillard, Eric

"The Flamenco Academy" by Sarah Bird

Sweet's Journey by Erin Hunter

The Owned Girl by Dominic Ridler

The Trouble with Lexie by Jessica Anya Blau