When My Name Was Keoko (3 page)

Read When My Name Was Keoko Online

Authors: Linda Sue Park

Onishi-san heard me. He made a funny sound in his throat, like "Ah!" Then he looked at the teacher and made an abrupt motion with his stick.

The teacher glanced at him quickly and then at me. "Keoko! To the front," she said.

The class was suddenly silent. I could see the surprise in the faces of the other students. The daughter of the vice-principalâwho had never before been beaten...

In the brief moments it took me to walk to the front of the class, I saw the teacher's face. She looked so unhappy that I felt sorrier for her than for myself. She didn't want to beat me, but she had toâbecause Onishi-san was there.

It was so unfair. First our names were taken away, and then we weren't given even a few days to learn everyone's new name.

So when the bamboo cane swished through the air I was angry, not frightened. With each stinging whack, the word rang in my mind ...

unfairâunfairâunfairâunfairâunfair

.... Best of all, I was too angry to cry.

At home that night Omoni pressed her lips together when she saw the fierce red welts on my legs. She soothed them with a paste made of herbs, but the marks stayed there for several days. I was glad they didn't fade right away. Seeing and feeling the sore redness of those welts always made me a little angry all over again.

I wanted to stay angry about losing my name.

***

The changing of my name made even Tomo cross. When we played together after school during those early days of the name change, he kept catching himself. "Sun-heeâI mean, Keoko," he kept saying.

Once, after correcting himself for what seemed like the hundredth time, he stamped his foot in frustration. "Keoko-Keoko-Keoko," he said, as if trying to pound the name into his brain. "Keoko-Keoko-Keekeeko-Kekokoâ" He was getting his tongue all twisted.

I giggled. "Kee-kee-ko? Ke-ko-ko?"

"Ke-ya-koo! Ko-ko-ka!"

Now we were both laughing.

"Ka-koo-ko!"

"Ke-ay-ka!"

Tomo was laughing at the silly sounds. I was laughing for the same reason, but I was also secretly pleased to be treating my Japanese name with such disrespect.

At last our laughter faded and we caught our breath. Tomo glanced at me quickly, then looked away again. "Maybe, when it's just the two of us alone, I could still call you Sun-hee. What do you think?"

It wasn't often that Tomo asked for my opinion. I wanted to answer carefully, so I thought for a moment. "Wouldn't that just make it harder?" I said. "You'd have to switch to my Japanese name when we're with other people. You might get mixed up andâand forget."

I didn't say all that I was thinkingâthat as the son of the principal, Tomo always had to set an example. A mistake from him would be worse than a mistake from other students; he would lose a lot more face. I didn't have to say it, because it was something Tomo lived with every day.

"You're right," he said. He flicked another glance at me. "It's such a nuisance, isn't it?"

And I knew this was his way of saying he was sorry I had to change my name.

It was our last year of school together. Elementary students all went to the same school, but in junior high, boys and girls went to separate schools.

Not that Tomo and I saw each other much in school anyway. The Japanese students had their own classrooms. Tomo had told me that in bigger cities the Japanese had their own

schools.

But our town was too small for that.

I only saw Tomo at assembly times, which were in the morning, when the whole school met in the courtyard to recite the Emperor's education policy. We also sang the Japanese national anthem and did exercises together. And once in a while there were special assemblies.

Even though I couldn't read Japanese when I first went to school, knowing how to speak it made all the lessons much easier for me. At the start of my second year I was made Class Leader because I was the best in my class at reading and writing.

We had to learn three kinds of writing. Two kinds used the Japanese alphabet, and there were two different alphabets. The third system, which most of my classmates found terribly difficult, was called

kanji.

Kanji has no alphabet. Instead, each word is a separate picture-character. Altogether there are nearly fifty thousand characters! Not even scholars who spend their whole lives studying kanji can learn them all. We had to learn about two thousand basic charactersâto recognize them in reading and to write them ourselves.

We had calligraphy lessons as part of studying kanji. I loved calligraphy the very first time I tried it. It seemed that an unknown creature came to life in the brush as soon as I picked it upâa creature light as a dragonfly, smooth as a snake, quick as a rabbit.

The combinations of kanji characters were like magic to me. For example, the character for "love." You wrote the character for "mother" and combined it with the one for "child." When stroked with the brush rather than sketched out with a pencil, the word truly did look more loving.

Every week we learned new characters. Sometimes the connections were easy to understand. The character for "life" was formed by writing "water" plus "tongue"âfor without water to drink there can be no life. The characters "rice" and "mouth" together made "happy" or "peaceful." It was trueâhow could you be happy or at peace if you were starving?

Kanji was full of secrets like this. Tae-yul hated studying kanji; he thought it was boring. I couldn't understand that at all. Maybe I loved kanji because it was about knowing a little and figuring out the rest.

Abuji noticed my interest in kanji and began to spend more time with me. Before, Omoni had always looked after us; Abuji was busy with his own work. Until he started to help me study kanji, I'd spent very little time with him.

My lessons in school concentrated on learning and memorizing characters. This was so difficult and took so much time that the teachers didn't explain much about each individual character. Abuji took my learning a step furtherâor rather, a step backward.

One night we sat together at the low table in his room, bent over a sheet of paper.

"Mouth," he said as he wrote the character: "This is very simple. It began as a circle, like an open mouth, but the line was squared to make it easier to combine with other characters.

"This is very simple. It began as a circle, like an open mouth, but the line was squared to make it easier to combine with other characters.

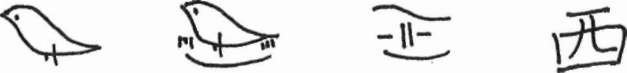

"West. As the sun goes down, the birds fly back to their nests. So you seeâ" and he drew for me the progression of pictures that had evolved into the character for "west."

I loved these sessions with Abuji. I watched with my eyes and listened with my ears and learned with my heart. My kanji got better without it ever feeling like work.

At the end of my fourth year of school I was awarded a special prize for my language skills. All students wore two badges on their collars, one with the school's name and the other with their graduation year. I was given a third badge to wear. It meant I was the best in my grade at Japanese. It was the proudest moment of my life when the principal pinned the badge to my collar in front of the entire school. I didn't look at Abuji, but I could feel how proud he was.

As I left the platform to rejoin my class, Tomo smiled at me with his eyes. I was so surprised and pleased that I almost stopped walking. Tomo and I never talked to each other at school. Even when I did see himâin the courtyard before school or during assembliesâI pretended I didn't know him, and he did the same with me. It was just the way things were: Japanese and Korean children didn't mix during school.

Tomo must have noticed my surprise, for he quickly looked away. But that didn't bother me. Nothing could have

bothered me as I walked back to my seat. I felt as if I were floating on a bright rosy cloud.

That afternoon on my way home from school I felt something whiz past my ear. I turned around quickly, ducking just in time as a second pebble flew past. I kept my head down but glanced around wildly. Who was throwing stones at me?

At that moment a gang of boys from school dashed out from behind a wall. They threw a final volley of pebbles at me, then ran away, chanting: "

Chin-il-pa! Chin-il-pa!

"

Chin-il-pa

meant "lover of Japan." It was almost like a curse.

Chin-il-pa

were people who got rich because they cooperated with the Japanese government. I hadn't done anything like that! Why were they cursing me, calling me that awful name? I ran home, blinking away tears.

That evening I was distracted during my kanji session with Abuji. He was showing me "north"âtwo men sitting back-to-back at the top of the worldâas I stared not at the paper but at the shining new badge on my collar.

The badge was the reason those boys had thrown stones and called me names. I was good at Japanese. They thought that made me

chin-il-pa.

I wasn't a traitor, was I? Could you be a traitor without knowing it? Even to be called one was shameful.

Maybe I could take the pin off. But they'd all noticeâmy teachers, the principal, Abuji, everyone. Then I'd be in trouble at school as well.

I tried to make myself laugh inside by recalling Uncle's favorite joke about the

chin-il-pa:

"They eat Korean rice, but their poop is Japanese." But not even this cheered me.

Suddenly, Abuji put down the pencil and looked at me thoughtfully.

"You know, Sun-hee, kanji was not originally Japanese."

Not Japanese? What did he mean? I looked up at him, puzzled.

"Both Korea and Japan long ago borrowed the system of character writing from China. The Japanese use it in their own way, of course, especially when they combine it with their alphabetic writing. But the characters are the same. This"âhe picked up the pencil again and pointed to the pageâ"is the character for north' in Japanese

and

in Chinese. And in Korean as well."

Abuji stacked the books neatly, rolled up the paper, and put away the ink pot. I stood and bowed to him, preparing to leave the room.

He spoke again. "Your grandfather was a great scholar. He knew much of the important classical Chinese literature. In his time and for hundreds of years before his time we Koreans always considered Chinese the highest form of learning." He paused and looked at me calmly. "To excel at character writing is to honor the traditions of our ancestors."

I hadn't realized that my worries were showing on my face, but Abuji had noticed. What he'd said was meant to comfort me and to make me feel proud inside myself again.

I nodded, hoping he understood my silent thanks. If those boys called me

chin-il-pa

again, I could reach inside and hold on to the knowledge he'd given me.

Abuji and Sun-hee spend hours studying kanji together. I sit with them sometimes, but I can't figure out why they think it's so interesting. Kanji is a complete bore.

I do my best in school, but really I hate it. Not that

I'm a bad student. I always know my lessons. Son of the elementary-school vice-principalâit would be shameful if I did poorly. But I've never been Class Leader either.

Abuji doesn't scold me about my grades. When I was younger, I used to wonder about it, why he didn't get angry with me. Surely he

felt

angry. He was such a good scholar, just like his father. Both of them had been Class Leaders their whole lives. Whenever I show Abuji my marks, he always looks disappointed. But he never yells at me.

Science and mathematics lessons aren't too bad. But we study those subjects for only a little while each day. Most of the time we study Japanese. Japanese and more Japanese. And kanji is the worst of all.

Each word is a separate character, and some characters look alike. A single brushstroke makes the difference between "sky" and "big." Two characters close together often make a whole new word. Who thought up this stuff? They must have tried on purpose to make it confusing. I spend hours studying kanji, until the strokes and lines look like one big blur on the page.

Sun-hee actually

likes

kanji. When she first started school, she asked for my help. But pretty soon she got really good at it. Now she knows as many characters as I do. More, probably.