What to expect when you're expecting (126 page)

Read What to expect when you're expecting Online

Authors: Heidi Murkoff,Sharon Mazel

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Postnatal care, #General, #Family & Relationships, #Pregnancy & Childbirth, #Pregnancy, #Childbirth, #Prenatal care

These are just three of the very different ways that a woman may carry near the end of her eighth month. The variations are even greater than earlier in pregnancy. Depending on the size and position of your baby, as well as your own size and weight gain, you may be carrying higher, lower, bigger, smaller, wider, or more compactly.

In other words, it’s what’s inside that counts—and apparently, what’s inside your petite belly is a baby who’s plenty big enough.

“Everyone says I’m having a boy because I’m all belly and no hips. I know that’s probably an old wives’ tale, but is there any truth to it at all?”

Predictions about the baby’s sex—by old wives or others—have about a 50 percent chance of coming true. (Actually, a little better than that if a boy is predicted, since 105 boys are born for every 100 girls.) Good odds if you’re placing a bet in Las Vegas; not necessarily good odds if you’re basing your nursery theme and baby names on it.

That goes for “boy if you’re carrying up front, girl if you’re carrying wide,” “girls make your nose grow, boys don’t,” and every other prediction not made from the pages of a baby’s genetics report or from an ultrasound.

“I’m five feet tall and very petite. I’m afraid I’ll have trouble delivering my baby.”

When it comes to your ability to birth your baby, size matters—but inside size, not outside size. It’s the size and shape of your pelvis in relation to the size of your baby’s head that determines how difficult (or easy) your labor will be, not your height or your build. And just because you’re extra petite doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve got an extra-petite pelvis. A short, slight woman can have a roomier (or more accommodatingly configured) pelvis than a tall, full-figured woman.

How will you know what size your pelvis is (after all, it doesn’t come with a label: small, medium, extra-large)? Your practitioner can make an educated guess about its size, usually using rough measurements taken at your first prenatal exam. If there’s some concern that your baby’s head is too large to fit through your pelvis while you’re in labor, ultrasound may be used to get a better view (and measurement).

Of course, in general, the overall size of the pelvis, as of all bony structures, is smaller in people of smaller stature. Luckily, nature doesn’t typically present an undersized woman with an oversized baby. Instead, newborns are usually pretty well matched to the size of their moms and their moms’ pelvises at birth (though they may be destined for bigger things later on). And chances are, your baby will be just the right size for you.

“I’ve gained so much weight that I’m afraid my baby will be very big and difficult to deliver.”

Just because you’ve gained a lot of weight doesn’t necessarily mean your baby has. Your baby’s weight is determined by a number of variables: genetics, your own birthweight (if you were born large, your baby is more likely to be, too), your prepregnancy weight (heavier women tend to have heavier babies), and the kinds of foods you’ve gained the weight on. Depending on those variables, a 35- to 40-pound weight gain can yield a 6- or 7-pound baby and a 25-pound weight gain can net an 8-pounder. On average, however, the more substantial the weight gain, the bigger the baby.

By palpating your abdomen and

measuring the height of your fundus (the top of the uterus), your practitioner will be able to give you some idea of your baby’s size, though such guesstimates can be off by a pound or more. An ultrasound can gauge size more accurately, but it may be off the mark, too.

Even if your baby does turn out to be on the big side, that doesn’t automatically predict a difficult delivery. Though a 6- or 7-pound baby often makes its way out faster than a 9- or 10-pounder, most women are able to deliver a large baby (or even an extra-large baby) vaginally and without complications. The determining factor, as in any delivery, is whether your baby’s head (the largest part) can fit through your pelvis. See the previous question for more.

“How can I tell which way my baby is facing? I want to make sure he’s the right way for delivery.”

Playing “name that bump” (trying to figure out which are shoulders, elbows, bottom) may be more entertaining than the best reality TV has to offer, but it’s not the most accurate way of figuring out your baby’s position. Your practitioner will be able to give you a better idea by palpating your abdomen for recognizable baby parts. The location of the baby’s heartbeat is another clue to its position: If the baby’s presentation is head first, the heartbeat will usually be heard in the lower half of your abdomen; it will be loudest if the baby’s back is toward your front. If there’s still some doubt, an ultrasound offers the most reliable view of your baby’s position.

Still can’t resist a round of your favorite evening pastime (or resist patting those round little parts)? Play away—and to make the game more interesting (and to help clue you in), try looking for these markers next time:

The baby’s back is usually a smooth, convex contour opposite a bunch of little irregularities, which are the “small parts”—hands, feet, elbows.

In the eighth month, the head has usually settled near your pelvis; it is round, firm, and when pushed down bounces back without the rest of the body moving.

Breech Baby

The baby’s bottom is a less regular shape, and softer, than the head.

“At my last prenatal visit, my doctor said he felt my baby’s head up near my ribs. Does that mean she’s breech?”

Even as her accommodations become ever more cramped, your baby will still manage to perform some pretty remarkable gymnastics during the last

weeks ofgestation. In fact, although most fetuses settle into a head-down position between weeks 32 and 38 (breech presentations occur in fewer than 5 percent of term pregnancies), some don’t let on which end will ultimately be up until a few days before birth. Which means that just because your baby is bottoms down now doesn’t mean that she will be breech when it comes time for delivery.

Turn, Baby, Turn

Some practitioners recommend simple exercises to help turn a breech baby into a delivery-friendly, heads-down position. Ask your practitioner whether you should be trying any of these at home: Rock back and forth a few times on your hands and knees several times a day, with your buttocks higher than your head; do pelvic tilts (see

page 224

); get on your knees (keep them slightly apart), and then bend over so your butt’s up and your belly’s almost touching the floor (stay in that position for 20 minutes three times a day if you can, for best results).

Face Forward

It’s not just up or down that’s important when it comes to the position of your baby—it’s also front or back. If baby’s facing your back, chin tucked onto his or her chest (as most babies end up positioned come delivery), you’re in luck. This so-called occiput anterior position is ideal for birth because your baby’s head is lined up to fit through your pelvis as easily and comfortably as possible, smallest head part first. If baby’s facing your tummy (called occiput posterior, but also known by the much cuter nickname “sunny-side up”), it’s a setup for back labor (see

page 367

) because his or her skull will be pressing on your spine. It also means your baby’s exit might take a little longer.

As delivery day approaches, your practitioner will try to determine which way (front or back) your baby’s head is facing—but if you’re in a hurry to find out, you can look for these clues. When your baby is anterior (face toward your back), you’ll feel your belly hard and smooth (that’s your baby’s back). If your little one is posterior, your tummy may look flatter and softer because your baby’s arms and legs are facing forward, so there’s no hard, smooth back to feel.

Do you think—or have you been told—that your baby is posterior? Don’t worry about back labor yet. Most babies turn accommodatingly to the anterior position during labor. Some midwives recommend giving baby a nudge before labor begins by getting on all fours and doing pelvic rocks; whether these exercises can successfully flip a baby is unclear (research has yet to back it up, so to speak), but it certainly can’t hurt. At the very least, it might help relieve any back pain you might be experiencing right now.

If your baby does stubbornly remain a breech as delivery approaches, you and your practitioner will discuss possible ways to attempt to turn your baby head down and the best method of delivery (see below).

“If my baby is breech, can anything be done to turn him?”

There are several ways to try to coax a bottoms-down baby heads up. On the low-tech side, your practitioner may recommend simple exercises, such as the ones described in the box,

page 317

. Another option (moxibustion) comes from the CAM camp and uses a form of acupuncture and burning herbs to help turn a stubborn fetus.

If your baby still seems determined not to budge, your practitioner may suggest a somewhat higher-tech, yet hands-on approach to manipulating your baby into the coveted heads-down position: external cephalic version (ECV). ECV is best performed around week 37 or 38 or very early in labor when the uterus is still relatively relaxed; some physicians prefer to attempt the procedure after an epidural has been given. Your practitioner (guided by ultrasound and usually

in a hospital) will apply his or her hands to your abdomen (you’ll feel some pressure, but probably no pain—especially if you’ve had an epidural) and try to gently turn your baby downward. Continuous monitoring will ensure that everything’s okay while the maneuver’s completed.

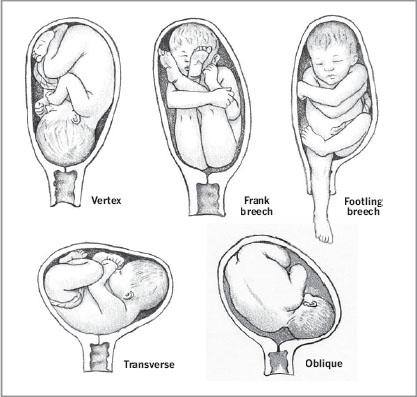

How Does Your Baby Lie?

Location, location, location—when it comes to delivery, a baby’s location matters a lot. Most babies present head first, or in a vertex position. Breech presentations can come in many forms. A frank breech is when the baby is buttocks first, with his or her legs facing straight up and flat against the face. A footling breech is when one or both of the baby’s legs are pointing down. A transverse lie is when the baby is lying sideways in the uterus. An oblique lie is when the baby’s head is pointing toward mom’s hip instead of toward the cervix.