What Technology Wants (30 page)

Read What Technology Wants Online

Authors: Kevin Kelly

Ted Kaczynski, of course, is not the only wilderness lover to suffer the encroachment of civilization. Entire tribes of indigenous Americans were driven to remote areas by the advance of European culture. They were not running from technology per se (they happily picked up the latest guns when they could), but the effect was the sameâto distance themselves from industrial society.

Kaczynski argues that it is impossible to escape the ratcheting clutches of industrial technology for several reasons: one, because if you use

any

part of the technium, the system demands servitude; two, because technology does not “reverse” itself, never releasing what is in its hold; and three, because we don't have a choice of what technology to use in the long run. In his words, from the manifesto:

any

part of the technium, the system demands servitude; two, because technology does not “reverse” itself, never releasing what is in its hold; and three, because we don't have a choice of what technology to use in the long run. In his words, from the manifesto:

The system HAS TO regulate human behavior closely in order to function. At work, people have to do what they are told to do, otherwise production would be thrown into chaos. Bureaucracies HAVE TO be run according to rigid rules. To allow any substantial personal discretion to lower-level bureaucrats would disrupt the system and lead to charges of unfairness due to differences in the way individual bureaucrats exercised their discretion. It is true that some restrictions on our freedom could be eliminated, but GENERALLY SPEAKING the regulation of our lives by large organizations is necessary for the functioning of industrial-technological society. The result is a sense of powerlessness on the part of the average person.

Another reason why technology is such a powerful social force is that, within the context of a given society, technological progress marches in only one direction; it can never be reversed. Once a technical innovation has been introduced, people usually become dependent on it, unless it is replaced by some still more advanced innovation. Not only do people become dependent as individuals on a new item of technology, but, even more, the system as a whole becomes dependent on it.

When a new item of technology is introduced as an option that an individual can accept or not as he chooses, it does not necessarily REMAIN optional. In many cases the new technology changes society in such a way that people eventually find themselves FORCED to use it.

Kaczynski felt so strongly about the last point that he repeated it once more in a different section of his treatise. It is an important criticism. Once you accept the fact that individuals surrender freedom and dignity to “the machine” and that they increasingly have no choice but to do so, then the rest of Kaczynski's argument flows fairly logically:

But we are suggesting neither that the human race would voluntarily turn power over to the machines nor that the machines would willfully seize power. What we do suggest is that the human race might easily permit itself to drift into a position of such dependence on the machines that it would have no practical choice but to accept all of the machines decisions. As society and the problems that face it become more and more complex and machines become more and more intelligent, people will let machines make more of their decision for them, simply because machine-made decisions will bring better result than man-made ones. Eventually a stage may be reached at which the decisions necessary to keep the system running will be so complex that human beings will be incapable of making them intelligently. At that stage the machines will be in effective control. People won't be able to just turn the machines off, because they will be so dependent on them that turning them off would amount to suicide. . . . Technology will eventually acquire something approaching complete control over human behavior.

Will public resistance prevent the introduction of technological control of human behavior? It certainly would if an attempt were made to introduce such control all at once. But since technological control will be introduced through a long sequence of small advances, there will be no rational and effective public resistance.

I find it hard to argue against this last section. It is true that as the complexity of our built world increases we will necessarily need to rely on mechanical (computerized) means to manage this complexity. We already do. Autopilots fly our very complex flying machines. Algorithms control our very complex communications and electrical grids. And for better or worse, computers control our very complex economy. Certainly as we construct yet more complex infrastructure (location-based mobile communications, genetic engineering, fusion generators, autopiloted cars) we will rely further on machines to run it and make decisions. For those services, turning off the switch is not an option. In fact, if we wanted to turn off the internet right now, it would not be easy to do, particularly if others wanted to keep it on. In many ways the internet is designed to never turn off. Ever.

Finally, if the triumph of a technological takeover is the disaster that Kaczynski outlinesârobbing souls of freedom, initiative, and sanity and robbing the environment of its sustainabilityâand if this prison is inescapable, then the system must be destroyed. Not reformed, because that will merely extend it, but eliminated. From his manifesto:

Until the industrial system has been thoroughly wrecked, the destruction of that system must be the revolutionaries' ONLY goal. Other goals would distract attention and energy from the main goal. More importantly, if the revolutionaries permit themselves to have any other goal than the destruction of technology, they will be tempted to use technology as a tool for reaching that other goal. If they give in to that temptation, they will fall right back into the technological trap, because modern technology is a unified, tightly organized system, so that, in order to retain SOME technology, one finds oneself obliged to retain MOST technology, hence one ends up sacrificing only token amounts of technology.

Success can be hoped for only by fighting the technological system as a whole; but that is revolution not reform. . . . While the industrial system is sick we must destroy it. If we compromise with it and let it recover from its sickness, it will eventually wipe out all of our freedom.

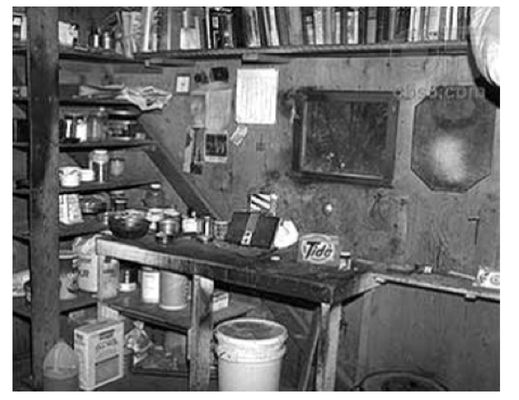

For these reasons Ted Kaczynski went to the mountains to escape the clutches of civilization and then later to plot his destruction of it. His plan was to make his own tools (anything he could hand fashion) while avoiding technology (stuff it takes a system to make). His small one-room shed was so well constructed that the feds later moved it off his property as a single intact unit, like a piece of plastic, and put it in storage (it now sits reconstructed in the Newseum in Washington, D.C.). His place was way off the road; he used a mountain bike to get into town. He dried hunted meat in his tiny attic and spent his evenings in the yellow light of a kerosene lamp crafting intricate bomb mechanisms. The bombs were strikes at the professionals running the civilization he hated. While his bombs were deadly, they were ineffective in achieving his goal, because no one knew what their purpose was. He needed a billboard to announce why civilization needed to be destroyed. He needed a manifesto published in the major papers and magazines of the world. Once they read it, a special few would see how imprisoned they were and would join his cause. Perhaps others would also start bombing the choke points in civilization. Then his imaginary Freedom Club (“FC” is how he signed his manifesto, written with the plural “we”) would be a club of more than himself.

The attacks on civilization did not materialize in bulk once his manifesto was published (although it did help authorities arrest him). Occasionally an Earth Firster would burn a building in an encroaching development or pour sugar into a bulldozer's gas tank. During the otherwise peaceful protests against the G7, some anticivilization anarchists (who call themselves anarcho-primitivists) broke fast-food storefront windows and smashed property. But the mass assault on civilization never happened.

The problem is that Kaczynski's most basic premise, the first axiom in his argument, is not true. The Unabomber claims that technology robs people of freedom. But most people of the world find the opposite. They gravitate toward technology because they recognize that they have more freedoms when they are empowered with it. They (that is, we) realistically weigh the fact that yes, indeed, some options are closed off when adopting new technology, but many others are opened, so that the net gain is an increase in freedom, choices, and possibilities.

Consider Kaczynski himself. For 25 years he lived in a type of self-enforced solitary confinement in a dirty, smoky shack without electricity, running water, or a toilet. He cut a hole in the floor for late-night peeing. In terms of material standards, the cell he now occupies in the Colorado supermax prison is a four-star upgrade: His new place is larger, cleaner, and warmer, with the running water, electricity, and the toilet he did not have, plus free food and a much better library. In his Montana hermitage he was free to move about as much as the snow and weather permitted him. He could freely choose among a limited set of choices of what to do in the evenings. He may have personally been content with his limited world, but overall his choices were very constrained, although he had unshackled freedom within those limited choicesâsort of like, “You are free to hoe the potatoes any hour of the day you want.” Kaczynski confused latitude with freedom. He enjoyed great liberty within limited choices, but he erroneously believed this parochial freedom was superior to an expanding number of alternative choices that may offer less latitude within each choice. An exploding circle of choices encompasses much more actual freedom than simply increasing the latitude within limited choices.

Inside the Unabomber's Shack.

Ted Kaczynski's library and workbench where he made bombs.

Ted Kaczynski's library and workbench where he made bombs.

I can only compare his constraints in his cabin to mine, or perhaps anyone else's reading this today. I am plugged into the belly of the machine. Yet technology allows me to work at home, so I hike in the mountains, where cougars and coyotes roam, most afternoons. I can hear a mathematician give a talk on the latest theory of numbers one day and the next day be lost in the wilderness of Death Valley with as little survivor gear as possible. My choices in how I spend my day are vast. They are not infinite, and some options are not available, but in comparison to the degree of choices and freedoms available to Ted Kaczynski in his shack, my freedoms are overwhelmingly greater.

This is the chief reason billions of people migrate from mountain shacksâvery much like Kaczynski'sâall around the world. A smart kid living in a smoky one-room hut in the hills of Laos or Cameroon or Bolivia will do all he can to make his way against all odds to the city, where there areâso obvious to the migrantâvastly more freedom and choices. He would find Kaczynski's argument that there is more freedom back in the stifling prison he just escaped from plain crazy.

The young are not under some kind of technological spell that warps their minds into believing civilization is better. Sitting in the mountains, they are under no spell but poverty's. They clearly know what they give up when they leave. They understand the comfort and support of family, the priceless value of community acquired in a small village, the blessings of clean air, and the soothing wholeness of the natural world. They feel the loss of immediate access to these, but they leave their shacks anyway because in the end, the tally favors the freedoms created by civilization. They can (and will) return to the hills to be rejuvenated.

My family doesn't have TV, and while we have a car, I have plenty of city friends who do not. Avoiding particular technologies is certainly possible. The Amish do it well. Many individuals do it well. However, the Unabomber is right that choices that begin as optional can over time become less so. First, there are certain technologies (say, sewage treatment, vaccinations, traffic lights) that were once matters of choice but that are now mandated and enforced by the system. Then there are other systematic technologies, such as automobiles, that are self-reinforcing. The success and ease of cars shift money away from public transport, making it less desirable and encouraging the purchase of a car. Thousands of other technologies follow the same dynamic: The more people who participate, the more essential it becomes. Living without these embedded technologies requires more effort, or at least more deliberate alternatives. This web of self-reinforcing technologies would be a type of noose if the total gains in choices, possibilities, and freedoms brought about by them did not exceed the losses.

Anticivilizationists would argue that we embrace more because we are brainwashed by the system itself and we have no choice but to say yes to more. We can't, say, resist more than a few individual technologies, so we are imprisoned in this elaborate artificial lie.

It is possible that the technium has brainwashed us all, except for a few clear-eyed anarcho-primitivists who like to blow up stuff. I would be inclined to believe in breaking this spell if the Unabomber's alternative to civilization was more clear. After we destroy civilization, then what?

Other books

Dakota Dream by Sharon Ihle

If He's Sinful by Howell, Hannah

The Last Knight by Hilari Bell

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea by J. L. Murray

Rough Rhythm: A Made in Jersey Novella (1001 Dark Nights) by Tessa Bailey

The Complete Short Fiction of Charles L. Grant, Volume IV: The Black Carousel by Charles L. Grant

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard

Paxton and the Gypsy Blade by Kerry Newcomb

Defy by Sara B. Larson