Wendy and the Lost Boys (23 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

His niece had no idea who he was. They talked past each other for a few minutes. When Jenifer explained that she was Sandra’s daughter, the man on the other end was equally baffled. Then an aide took the phone from Abner. Jenifer immediately called her mother, who filled the canyon-size gap in Jenifer’s family history.

When Georgette’s younger daughter, Melissa, was eight years old, Abner sent her a gold stickpin inscribed with her name. She told her mother she wanted to send her uncle a thank-you letter.

“Don’t,” Georgette said. “It upsets him.” She had encouraged her children to write to Abner until she’d received a letter from a social worker telling them to stop. The letters agitated him, making him aware of what he was missing, she was told, and the awareness sometimes triggered a seizure.

Georgette didn’t question the social worker’s instruction, nor did she discuss Abner with either of her sisters or Bruce. Lola sometimes gave Georgette a report, returning from Rochester either in good spirits because Abner said he had a girl friend or depressed because he’d had a seizure.

There was a recurrent theme. “Abner wanted to come home to the family, but the family wasn’t there,” said Georgette. “What house? What family?”

The lives of the other Wasserstein children had continued. The Brooklyn home Abner longed for was part of their past. His brother and sisters were adults, with concerns far removed from the isolated world he inhabited. For Abner, however, time had stood still. He was a middle-aged man equipped with the mind and heart of an inquisitive youngster, understanding that a larger life was passing him by but powerless to do anything about it. His lot was to feel, forever, the pain of a lost boy.

Part Three

ISN’T IT ROMANTIC

1980-89

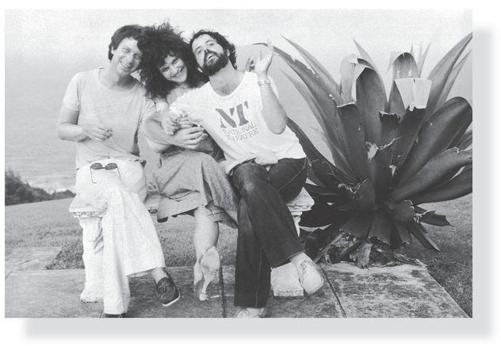

ANDRÉ, WENDY, AND GERRY DURING THEIR

NOËL COWARD VACATION IN JAMAICA.

Twelve

DESIGN FOR LIVING

1980-83

For years there was only

one photograph Wendy Wasserstein felt worthy of a Tiffany frame—a snapshot, taken at sunset on a Jamaica beach, at Firefly, the Caribbean home of Noël Coward. Wendy is sitting on a bench between two handsome young men, their arms intertwined. She is wearing a flowing Laura Ashley dress and looks tan and happy, face lit with a huge smile, kicking her feet (clad in red espadrilles) in the air.

It is the summer of 1982. To her right is André Bishop, smiling shyly at the camera, rosy-cheeked, wearing deck shoes and white slacks and a light T-shirt. To her left, Gerald Gutierrez, a rising young director and a new friend of Wendy’s, strikes a theatrical pose.

In memory the vacation became mythic, the moment that bonded the three of them for life. “In the theater one always forms instant families, but the next family forms with the very next rehearsal of the very next show,” Wendy wrote. “However, in Jamaica, Gerry, André and I became one another’s permanent artistic heart and home. During those nights . . . we formed with one another the opinions—and in the theater all you have is your opinions—which would always count, which would always matter.”

The three friends were about to collaborate on a project. The following year Playwrights Horizons was going to produce a new version of

Isn’t It Romantic,

Wendy’s play about a clever, overweight Jewish girl trying to break from her parents and find her own path. André was now in charge of Playwrights Horizons; a year earlier Bob Moss had officially handed the mantle of artistic director to his protégé. Gerry Gutierrez, who had just had a hit at the theater, was going to direct. (In May 1982 Gutierrez directed

Geniuses

by Jonathan Reynolds, which was well reviewed and then ran for a year.)

They were all in their early thirties and unattached. Both men were gay. Wendy called their three-week trip to Jamaica their

Design for Living

holiday, a nod to the Noël Coward play about three people “diametrically opposed to ordinary social conventions”—Otto, the painter; Leo, the playwright; and Gilda, the golden girl they both loved.

Later she gently mocked her own romantic vision. “None of us really opposed social conventions,” Wendy wrote of her budding relationships with André and Gerry. But their friendship was emblematic of the new social order. Just twenty years earlier, 25 percent of women between the ages of twenty and twenty-four were single, compared with 50 percent in 1980. As women delayed marriage, they created more intimate connections with friends, male and female.

They rented a villa, equipped with a pool, a kitchen, three bedrooms, and two maids, called Mrs. Henry and Julia. The housekeepers did not seem to approve of their guests and their high-spirited enthusiasm for one another.

Every night Mrs. Henry and Julia prepared specialties like callaloo and saltfish, local dishes that went unappreciated by their guests. As Wendy wrote, “André is allergic to fish, I prefer candy, and Gerry is a vegetarian.” They stayed up all night drinking beer and eating saltines covered with Velveeta cheese spread, arguing about the theater.

They paid homage to the playwright at his gravesite overlooking the ocean, by smoking cigarettes and drinking the dry gin martinis they’d brought in a thermos and calling one another “darling” as they imagined Sir Noël would if he were there. The sun and booze made Gutierrez extra buoyant. He quoted Leo, from Coward’s

Design for Living:

“The actual facts are so simple,” he said to André and Wendy. “I love you. You love me. You love Otto. Otto loves you. There now! Start to unravel from there.” Someone snapped their picture.

Gerry Gutierrez, enchanting and volatile, reminded Wendy of the parts of Lola she liked, the lively, funny, unpredictable parts, the go-go without the meanness. (She hadn’t seen his moody side yet, the impatience that expressed itself in emotional outbursts, the demons that sent him into hiding.) André was sensible and sweet, glad to go along for the ride, reserved, supportive—reminiscent, perhaps, of Morris.

They swapped stories about their families. Gerry’s father was a police detective. Gerry had grown up in Brooklyn and attended Midwood High, the same school as Georgette, and received training in classical piano at Juilliard in Manhattan. After attending the State University of New York, he returned to Juilliard, where he studied drama with John Houseman, first as an actor but then finding his calling as a director. His mother worked as the office manager for Elizabeth Holtzman, a prominent New York politician, but—like Lola—Obdulia (called Julie) Gutierrez was a dancer; flamenco was her specialty.

Wendy and Gerry were familiar to each other. They were Brooklyn-born children from ethnic families to whom they remained attached. The two of them were captivated by tales of André as a child, a rarefied creature, descended from the world of Edith Wharton. As he traced his DNA back just a generation or two, they felt directly connected to the gilded society found in Noël Coward’s plays.

André patiently explained his complicated background. His mother, born Felice Rosen, was the child of New York Wasp royalty (her mother was Mary Bishop Harriman) and a wealthy immigrant Jew (Felix Rosen). Mary Bishop Harriman Rosen left Felix and their daughter to marry Pierre Lecomte du Noüy, a distinguished French philosopher and scientist, with whom she lived in France.

Felice remained with her father in New York, raised by governesses and attending a private school where girls named Rosen were not made to feel welcome. She rid herself of her Jewish-defining surname as quickly as she could, by marrying a southern Protestant named Hobson. They had a son, George, and then divorced. Felice next married a Russian émigré, André V. Smolianinoff. They named their son André Bishop Smolianinoff. They divorced; Felice remarried again. She then deposited young André, age seven, in a Swiss boarding school, less than a year after his father died, at age forty-five. She enrolled her son as André S. Bishop, sparing him the potential for insult embedded in the foreign, unpronounceable Smolianinoff (even his father had jokingly referred to himself as “André Smiling On and Off”).

What could be more sophisticated? André came from a world populated by railroad barons and dashing heiresses who defied their families by marrying Jews (his grandmother’s path) or fleeing to Europe and having tragic affairs (as his mother did, before her first marriage). He had grown up among the New York gentry. His summers were spent on Martha’s Vineyard with regular visits to Caramoor, an hour’s drive north of Manhattan, the ninety-acre estate surrounding the Mediterranean-style mansion built by his great-uncle Walter Rosen (the railroad baron) and his wife, the former Lucie Bigelow Dodge.

10

But as a boy he was often on his own, and unhappy, having lost his father and not caring much for his stepfather. André was educated at boarding schools, ultimately graduating from St. Paul’s in Concord, New Hampshire, an upper-crust Episcopal school, (alumni include Senator John Kerry and Garry Trudeau, the

Doonesbury

cartoonist) before following the prescribed path, to Harvard.

André was dimly aware of his Jewish ancestry, far more conscious of his mother’s aversion to her own Jewishness. He was surprised at how attached she became to Wendy. Felice “Fay” Harriman Francis, as she ultimately called herself (after yet another marriage), also didn’t approve of overweight women, but she came to love Wendy and admire her. André felt that in Wendy, his mother—who hadn’t gone to college—saw everything she hadn’t accomplished.

After the Jamaica vacation, everything merged, the personal and the professional. So it seemed natural that, when the time came to promote the play, it became a family affair. The radio ads for

Isn’t It Romantic

featured their mothers, Lola, Julie, and Fay—formerly Liska, Obdulia, and Felice—bragging about their children.

A

ndré’s decision to produce

Isn’t It Romantic

was regarded as a rescue mission by Wendy’s friends. The play had been commissioned by the Phoenix in 1979, the follow-up to

Uncommon Women and Others.

Steven Robman had become the Phoenix’s artistic director, so he had even more reason to hope for a repeat success with the playwright.

Wendy’s first version of

Isn’t It Romantic

opened at the Phoenix on May 28, 1981. While

Uncommon Women

was remembered as an auspicious production, the Robman-Wasserstein collaboration on

Isn’t It Romantic

became a sore subject for many people, for different reasons.

Wendy had struggled to find a workable idea for a new play. She wanted to write about her family; she was also drawn to the questions raised in

Uncommon Women,

now perplexing her in a different way. “I was 28 or so, and suddenly there was this question of all these biological time bombs going off,” she told an interviewer. “I had never thought about it before, because there was this pressure when I was getting out of Holyoke in 1971 to have a career. If you said you were getting married back then, it was embarrassing. And then suddenly, all these people were talking about getting married and having babies. Things had somehow turned around and I was trying to figure it all out.”

Her notebooks in 1980 and 1981 are filled with character sketches and snatches of dialogue, more crossed out than not.

The Phoenix production of

Isn’t It Romantic

seemed jinxed from the moment the sprinkler system went off onstage, right before a matinee performance. The performance was canceled. A frantic Robman went to the yellow pages and found Disaster Masters, a company that promised to quickly deal with the damage.

When Wendy arrived at the theater, she howled with laughter when she learned that Disaster Masters was coming in to save the day. By the evening performance, everything was up and running. After that, every time something went wrong with the show, Wendy giggled and said, “Let’s call Disaster Masters.”

For Steve Robman, however, Disaster Masters came to sum up the entire experience, and it wasn’t funny. Unlike

Uncommon Women,

which Wendy had spent years writing and revising in workshops at Yale and then the O’Neill,

Isn’t It Romantic

went into production direct from the page. And the pages kept changing; Wendy was rewriting throughout rehearsals, until the day the play opened.

“Wendy was bubbling over with humor and information and insights,” said Bob Gunton, the actor playing the Wasp boss having an affair with his employee. “I had the feeling she was trying to cram it all into this already fairly slenderly plotted play. She trusted Steve to help her shape this into a viable evening of theater.”

Robman realized later that they should have taken more time. “I was young and hardheaded or stupid or naïve, thinking we could get the work down in rehearsal,” he said.

Always blunt, Robman had become more critical as time ran out and the pressure built. Now he was no longer a director-for-hire but in charge of the long-running theater company’s artistic destiny. He was counting on Wendy to come up with a success like

Uncommon Women.

He told her to spend less time eating cookies and more time cutting and revising—in his mind a joke, in hers a jab.

Expectations were high. The

New York Times

ran an affectionate Sunday preview piece, a profile of Wendy, in which she is described as “one of a growing number of women playwrights currently making their mark on the theatrical scene—and, in the process, broadening its scope.”

Opening night, however, was not a repeat of the joyous celebration that had accompanied

Uncommon Women.

Steve Robman was tense, already upset with Wendy, who’d told him less than a month earlier that she planned to leave the Phoenix and do her next play at Playwrights Horizons; André Bishop had been building a cadre of writers and asked her to be part of it. He wanted Wendy back in his fold.

Robman and Wendy complained about each other to their friends but maintained a surface of cordiality at work. Following theater custom, Robman gave her an opening-night gift—a gift he would forget about but one that she always remembered. To memorialize his persistent request for cuts, the director presented her with a pair of scissors.

The playwright was not amused.

Wendy never forgave the scissors. Eleven years later, speaking before an audience of theater people and others, Wendy said, “There was this director who shall go nameless who gave me a pair of scissors on opening night because he thought the play was too long,” she said. “My advice is, ‘Don’t work with directors who give you scissors on opening night.’ ”

Walter Kerr, the influential Sunday critic, offered his assessment, on June 29, 1981, the day of the final performance. He began with a disarming preamble, praising the writing for several paragraphs, making it clear that he saw depth beneath the humor” If the playful little bypass is fun, it’s more than that,” he wrote of one exchange. “Its implications—the gap between the lines, the stammer at the heart of things, the tumble into uncertainty—is precisely what author Wasserstein means to write about.”