Wendy and the Lost Boys (14 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

Early in 1973 Louise Roberts called Moss to ask a favor. She’d run into a woman whose daughter used to take classes at the June Taylor dance school. The daughter was studying with Israel Horovitz at CCNY and had written a play. Would he take a look?

He agreed to read

Any Woman Can’t

by Wendy Wasserstein, a one-act she described as “the story of a girl who gives up and gets married after blowing an audition for tap-dancing class.” Moss liked Wendy when they met. He thought her play was funny but insubstantial. He put it in the 10:00 P.M. slot for five nights that April.

The play was Wendy’s response to

Any Woman Can!

, a guide to sexual and personal fulfillment published in 1971 by David Reuben, a physician and “sex expert,” who had gained national notoriety two years earlier with the publication of

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask)

. The play’s story is essentially “The Solid Gold Blender” in dramatized form. The heroine—Wendy’s alter ego—is called Christina. She is a recent Smith College graduate now working as an instructor at a Fred Astaire Dance Studio. Her boyfriend, Charles—modeled on James—is a straitlaced young man who alternately criticizes and seduces Christina, referring to her as “Teeny” and “Pet Tuna.” Christina has an overweight, overbearing boy-genius brother (like Bruce), who patronizes his gem-collecting wife (like Lynne).

During the play’s brief run, Wendy’s family and friends trooped into the Clark Center to see what she’d been up to at CCNY.

James Kaplan soon recognized himself in Charles. It was like seeing himself in a funhouse mirror, except that the distortion was not much fun. It was hard not to feel sucker-punched when Charles’s girlfriend, the Wendy character, yells at him, “I’m not ‘ladylike.’ I’m not one of those nice girls all your friends at Princeton kept as masturbating dollies. I hate your friends, and I hate you.”

James couldn’t bring himself to confront Wendy directly. He suggested afterward that maybe the actor hadn’t played the role properly. She saw how hurt he was, so she agreed. She said something about “poetic license.”

She told him, “You can’t view characters in a play as real.” He accepted her explanation, though he knew that changing details like Yale to Princeton didn’t cushion the harsh judgment being rendered.

He wondered what he was supposed to think, when Christina says, “I was just being cool and biding time in college until something happened to me. Nothing happened. Look, here I am with you.”

They continued to see each other, even though Wendy reported to James that someone had said to her, with surprise, “You’re still going out with that guy?”

Bruce had read the play and urged Lynne not to go see it, but he didn’t tell her why. She ignored him. She still thought of Wendy as her best friend and wouldn’t miss the production of her first play.

Lynne went to the Friday-night performance of

Any Woman Can’t

. When she saw a version of herself lying on a rug playing with rocks, she was annoyed. She was a member of the New York Lapidary Society and considered herself a craftswoman, not some bimbo.

She thought it was pretty silly—until the play struck an essential nerve. Mark, the Bruce character, has just sent his wife into the kitchen to get him a Yoo-Hoo, “like a good girl.” After she leaves, Christina—the Wendy stand-in—says to her brother, “I wouldn’t let someone treat me the way you treat her.”

Over the weekend Lynne couldn’t stop thinking about Wendy’s evaluation of her marriage—and of her. Bruce was interesting and intelligent and exciting, but what was Lynne? Suddenly she knew. Lynne was unhappy.

That Sunday evening she and Bruce were working on their taxes. They began arguing over who should balance the checkbook. As the fight escalated, Lynne glanced at the television.

Mayerling

, the movie that was on in the background, seemed like an omen. There were Omar Sharif and Catherine Deneuve, playing doomed lovers at the end of the Hapsburg Empire.

Just after midnight Lynne called her parents and asked them to come and get her. Subsequently she told Bruce she wouldn’t come back to him unless they went to a marriage counselor.

“He said, ‘If you don’t like it, get out,’” she recalled. “I didn’t like it, I got out. He was not a flexible person.”

W

endy would come to hate

Any Woman Can’t.

In 1997, in a lengthy interview with Laurie Winer, a drama critic, in the

Paris Review

, Wendy mentioned the play, and Winer said, “I’ve never seen it.”

“And you never will,” Wendy replied. “It’s an awful play.”

Yet she had sent that “awful” play to the Yale Drama School as part of her application for entry in the fall of 1973. By the time

Any Woman Can’t

was performed at Playwrights Horizons, Wendy had already been accepted at both Yale Drama and Columbia Business School and was leaning toward New Haven.

After the reading, Bob Moss said to her, “Why do you have to go? You can’t learn playwriting in school.”

But Wendy believed in the power of pedigree and connections. She chose Yale. The school became an important stepping-stone, though not exactly in the way she might have expected.

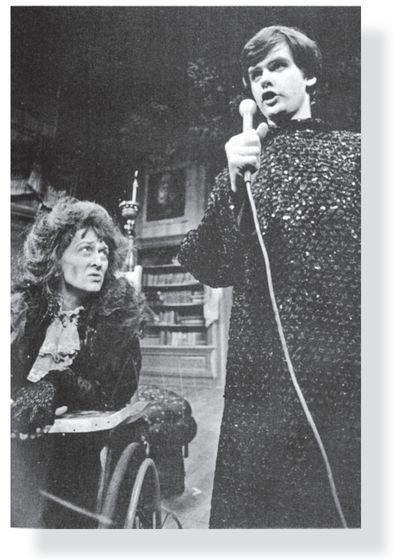

CHRIS DURANG AND MERYL STREEP,

SUPERSTARS AT YALE DRAMA WHEN WENDY

WAS THERE, HERE IN A PRODUCTION OF

THE IDIOTS KARAMAZOV

, WRITTEN BY

DURANG AND ALBERT INNAURATO.

Seven

DRAMA QUEENS AND KINGS

1973-76

The spring before Wendy arrived at Yale,

Christopher Durang had already begun to anticipate her arrival. As a work-study student, then in his second year, he had a job in the bursar’s office and sneaked a look at her application. He insisted that he wasn’t in the habit of snooping through the files of applicants but confessed he couldn’t resist spying on this one. He had heard that Richard Gilman had read a play by somebody named Wendy Wasserstein and liked it. Gilman, a respected critic, was the professor at the school who pretty much determined which playwrights were chosen. This Wasserstein woman was therefore likely to be admitted.

Chris was intrigued, especially when he saw recommendations from Joseph Heller, the bestselling novelist, and from Israel Horovitz, a well-known playwright. Then he looked at her photo. “Her arms were crossed, and she looked really grouchy, not a friendly person,” he recalled. “She looked defensive and/or maybe hostile and/or definitely suspicious of the world.” The play that was part of her admissions package carried a title Chris thought to be vaguely confrontational:

Any Woman Can’t.

Warily, he began reading the play, anticipating a feminist screed. Everything seemed to be political then. On April 30, 1973, about the time Chris was reading Wendy’s application, Richard M. Nixon made his first public reference to Watergate, the political burglary that would end his presidency. The war in Vietnam had shifted to Cambodia, where U.S. bombs were devastating the country. The Supreme Court had, in January, issued a landmark decision,

Roe v. Wade,

which in declaring that women had the constitutional right to an abortion ignited an intractable political battle resonant with biblical ferocity and certitude.

Chris Durang was not apolitical, but he preferred humor to harangues. Descended from a lineage of alcoholics and depressives, many of whom were artists, he began writing plays in third grade. However, the precocious boy didn’t start plumbing the darker corners of existence until his freshman year at Harvard, when he wrote, directed, and acted in a play called

Suicide and Other Diversions

. The play that had won him entry to Yale Drama,

The Nature and Purpose of the Universe,

was a comedy based on the book of Job. Howard Stein, the associate dean at the drama school, described Durang’s work “as a scream for help in a world he knows provides none. So he keeps on screaming and laughs at it.”

As Chris began reading

Any Woman Can’t,

he was surprised to find himself laughing, almost from the beginning. The story of a young woman trying to figure out what to do with the rest of her life was told with self-deprecating humor. He found the writer’s amusing depiction of the dating scene human, not didactic. His curiosity was even stronger than before.

When school resumed in the fall, he hoped to take a class with Terrence McNally, an up-and-coming playwright teaching a seminar at Yale that year. But McNally was a hot item; his class filled quickly, and Chris was stuck with a teacher he sensed was going to be a bore.

Soon he recognized a possible diversion. There was Wendy Wasserstein, hunkered down with her arms crossed, looking grouchy, just as she had in the photograph he’d seen in her application folder. Despite her forbidding appearance, because he’d read her play and thought it was funny, he felt they might be kindred spirits. “You must be very smart to be bored so quickly,” he said slyly, with the cherubic smile that led Robert Brustein, head of the drama school, to fondly refer to him as “a choirboy with fingers dipped in poison.”

Wendy responded with the expression Chris would always associate with her. “Her face lit up, and she laughed and laughed, and I felt that I had met Wendy,” he said. When she told him that a professor had once called her a “vicious dumpling,” he understood why. The rapier intelligence and shrewd wit, which could be delightfully rude, were kept wrapped inside that shy, unthreatening chubby-girl exterior.

The story of their first meeting would become part of their repertoire; Wendy incorporated it into

The Heidi Chronicles.

Her heroine Heidi meets a boy she would fall in love with at a high-school dance. His name is Peter Patrone. Their first exchange:

Peter:

You must be very bright.

Heidi:

Excuse me?

Peter:

You look so bored you must be very bright.

After class Chris invited Wendy for a cup of coffee. When he had to leave, he felt they had much more to say to each other. They met again for drinks the next day

She was a giggler; he was a mischief maker. They shared a cockeyed view of the world but could be quite serious, especially after their friendship deepened, and they began revealing secrets to each other. When Chris confessed that he had peeked at her application, Wendy admitted that before she arrived at Yale she had studied the list of people who were already there. When she saw “Christopher Durang, Harvard College, author of

The Nature and Purpose of the Universe,

” she told him, she assumed he would be a scary, smart Harvard jock full of self-confidence. They were both amused by the odd assumptions they’d made about each other and quickly became inseparable.

Wendy was smitten. “She provided 24/7 worship,” said Albert Innaurato, a classmate of Chris’s, who like Wendy had had an early play produced at Playwrights Horizon by Bob Moss.

Albert was a close friend of Chris’s, along with another third year student, Sigourney Weaver, an aristocratic-looking (but messy) Stanford graduate, who shared their zany take on the world. The three made a visual impact separately and together: Sigourney was five feet, ten and a half inches and quite beautiful. Albert was large, and Chris was small. Albert and Chris often worked together, as writers and actors. Their first year Sigourney appeared in one of Chris’s early comedies about a dysfunctional family,

Better Dead Than Sorry,

cast as a young woman who was constantly having nervous breakdowns. Chris played her worried brother.

The Idiots Karamazov,

a joint creation of Chris and Albert’s, a spoof of Dostoyevsky, became a favorite student production of Bob Brustein. Meryl Streep, in the class after Chris’s, was cast as the wheelchair-bound “translatrix,” whirled around the stage by “Ernest Hemingway,” her mute lover. Streep, an ethereal blond beauty, was transformed into an old hag, complete with a wart on the end of her nose. This tour de force was the kind of boundary-stretching phenomenon that might leave ordinary mortals feeling perplexed, even as they laughed, but Brustein adored it, describing it in the loftiest of terms: “

The Idiots Karamazov

hammered away at the most beloved works and authors in literature, leaving Western culture in momentary ruins, like the detritus of a dead civilization.”

Both Albert and Chris had large roles in a play the year Wendy arrived. Albert was annoyed to find her always sitting on the steps leading to the dressing room when he arrived for rehearsals. “What are you doing here?” he asked.

“I’m waiting for Chris.”

Five hours later, when Albert emerged, Wendy was still there, sitting on the steps, waiting for Chris.

There was jealousy. Albert and Chris collaborated so frequently that they were referred to as “Chris ’n’ Albert.” Albert felt that he was being edged out by Wendy, a newcomer he didn’t quite trust.

Albert didn’t exactly dislike Wendy, but he thought the first-year student was a little presumptuous, always hanging around them—make that Chris—all the time. Her devotion bothered Albert, because Chris was gay and Wendy knew it, yet she was behaving like a love-struck puppy.

But was it so strange, given Chris’s charming personality and exalted place in the cloistered atmosphere at Yale Drama? Chris had become a superstar at Yale, as both an actor and a playwright. He was a pet of Brustein; the school’s dictatorial dean ruled his small empire as if it were the center of the universe. Brustein’s teaching philosophy mimicked the brutal distillation process his students would encounter in the real world of theater. Both brilliance and pettiness were fostered by this approach, which nurtured certain dispositions and threatened to destroy others. Brustein saw the drama school as an ancillary program to his passion, the Yale Repertory Theatre. His goal was to produce not academics but working professionals. Brustein had strong opinions—hated the work of Arthur Miller, loved Bertolt Brecht.

He dismissed playwrights and actors who fell below his standard of “poetic consciousness,” which he associated with wild farce and dark surrealism. He expected his students to drive themselves to startling, unconventional dimensions; this pressure-cooker methodology produced some genius but even more anxiety and feelings of failure.

Brustein became Wendy’s nemesis, a stand-in for Lola, always ready to point out her shortcomings. It wasn’t her imagination. “I thought she was a lightweight,” said Brustein. “She was witty and funny and a little sitcom-y. In my Puritan way, I was trying to push playwrights in more dangerous areas. What appealed about Chris Durang was his outrageousness. Wendy seemed more domestic and conventional.”

The men running the school wanted women to look and behave a certain way. Sigourney Weaver was beautiful but didn’t fit Brustein’s design; she was criticized in evaluations for looking like an unmade bed. “I had raggedy hippie clothes,” she said. “Long, torn, ripped skirts. They saw me as a leading lady, and I thought of myself as a comedienne. When they were going after me about not having any talent, the whole thing was about how I dressed.”

Only select women’s issues were considered interesting. “The men were very much in charge of defining women’s pain,” said Susan Blatt, a classmate who became Wendy’s closest girlfriend at Yale. “Rape, childbearing, child losing—this was women’s pain. Dick Gilman, for example, was especially enamored of a play in which a retarded teenage girl is impregnated by an old farmworker and has an onstage farm-table abortion. Wendy’s oeuvre just wasn’t on the radar screen.”

Chris let Wendy know by their second or third coffee date that he was in a relationship—with a man—and had been for several years. Having made full disclosure, he preferred not to see the obvious. Wendy had a huge crush on him. He combined all the virtues she was looking for in a man. He was smart, funny, ambitious, wayward. He always took pains to compliment her. When they went to a thrift shop and she modeled a clingy evening gown with a marabou collar, he told her she looked “really glamorous”—and meant it—so different from Lola’s horrified reaction when Wendy wore the dress to a family function.

Chris wasn’t in love with Wendy, but he loved her. As an only child, he was fascinated by her stories of the Family Wasserstein. They amused themselves for hours swapping funny stories about their eccentric families. When he first heard Wendy’s anecdotes about Lola pressuring her to marry a doctor or a lawyer, he laughed appreciatively, thinking these were mere comedy routines. But as he got to know Wendy better, he was troubled by the implicit and sometimes explicit message: “If you don’t have children and continue the line, your life is meaningless.”

Chris’s family was repressed and often angry, but he hadn’t been belittled by his parents. He had special antennae for adults whose behavior might disturb children. The first time he met Lola—during Wendy’s first year at Yale—she was dressed as Patty Hearst (for no apparent reason; it wasn’t Halloween), the publishing heiress who was kidnapped by political radicals in 1974.

Though Chris had heard many Lola stories by then, he was still taken aback by the sight of the skinny middle-aged woman, wearing a trench coat, waving a toy pistol and saying, “Guess who I am!”

He understood that it was a joke and thought it was funny, but then he wondered what this exhibition was all about. Coming from a household of alcoholics, he was accustomed to unexpected outbursts and unexplained silences, but it was Wendy’s turn to be taken aback when he seemed surprised by Lola’s behavior. “If someone is crazy and no one talks about it, you cannot know the truth of something,” he said. “The reality testing is off. You don’t know what normal is.”

He felt protective toward Wendy, and she trusted him. She told him, “I feel like I’m a car that doesn’t have bumpers.” But with Chris she felt safe— strong enough to cut the final thread connecting her to James Kaplan, completing the process that had begun with the Playwrights Horizons production of

Any Woman Can’t.

When she learned that James had begun to date someone else, Wendy toyed with the thought of telling Chris her true feelings for him. She also wondered what was wrong with her, tossing aside a viable romantic candidate like James and choosing instead to yearn for an impossible relationship.