We Sled With Dragons (7 page)

Read We Sled With Dragons Online

Authors: C. Alexander London

WE ARE AND ARE NOT

“SO TELL ME

about Santa Claus,” their mother said over the roar of the jet engines as they flew away from Djibouti aboard a private plane Corey had chartered in the desert. Being rich and famous had its advantages.

Oliver looked over at his sister. She looked back at him. Neither of them wanted to go first, because they were starting to wonder if they'd imagined the whole thing. It was too crazy to be real, right?

“Well,” Oliver started. “I was looking through the old explorer's journal we found in the Amazon and I saw these drawings of, like, Atlantis and stuff. And there was this guy in all of them who looked a lot like . . . you know . . .”

“Santa Claus?” said Corey Brandt.

“Yeah. And then we were in that movie theater, hiding from the pirates, and I, like, saw these visions of, you know . . .”

“Santa Claus?” said Corey Brandt.

Oliver nodded. “Celia saw them too. She also thought the guy looked like . . . you know . . .”

“Santa Clâ” Corey started.

“I did not,” said Celia. “It was just some bearded guy doing explorery things. It wasn't, like, a guy in a red suit with presents and stuff. I mean, he had a sack and white hair, but he could have been anyone.” She didn't want Corey to think she was totally nuts.

“That's totally nuts,” said Corey.

Celia sighed.

“Yeah, I guess it is kind of stupid.” She blushed. “But he did look a lot likeâ”

“No, no,” Corey interrupted her. “It's totally nuts because I was just thinking about making a TV Christmas special called

Saint Nick of Time,

where Santa Claus fights a zombie invasion of the North Pole to save the holiday season.”

“Okay,” said Oliver. “Now that is nuts.”

“I think it's based on a book,” said Corey.

“You know,” Qui said, leaning on the back of Celia's seat, “maybe the man you saw is Santa Claus and also not Santa Claus.”

“Don't you start getting all mysterious too,” Oliver grumbled.

“I think Qui understands this perfectly,” said Claire Navel. “In America we call Saint Nicholas by the name Santa Claus. He is based on the fourth-century Greek Saint Nicholas from the island of Myra, a worker of miracles and giver of gifts. In the Dutch tradition, he's called Sinterklaas, and in some legends, he's also been known as the Lord of the Sea.”

“Like Poseidon,” said Oliver. “The ancient Greek god of the sea.”

“And the patron of Atlantis,” added Celia.

“Okay,” their father called back to them. “How did you guys know that?”

“Educational programming,” the twins answered together.

“You know there are also those who believe in the Norse tradition,” said Professor Rasmali-Greenberg, turning around in his seat. “You see, some believe that Santa Claus is related to the ancient Norse god Odin, the All-Father, who lived in the great city of Asgard, who drank from the well of wisdom, and who watched the universe from the Tree of the World.”

“There were a lot of trees in the explorer's journal,” said Oliver.

“You all realize how crazy this is, right?” said Celia, who did not think anyone was reacting to this theory the way they should have. “I mean, Santa Claus and Poseidon?”

“And Odin, the All-Father,” added Oliver.

“Right,” said Celia. “It can't possibly have anything to do with Atlantis. There's not even such a thing as Santa Claus!”

“Is too,” said Oliver.

“Is not!” said Celia.

“Is too,” said Oliver.

“It's not crazy at all,” their mother said, stopping their argument. “In 1679, Count Olof Rudbeck in Sweden proposed the same theory about Atlantis in the Arctic as the home of all the ancient Norse gods and monsters. Asgard, city of the gods, could be Atlantis. Odin could be Santa Claus. Count Olof never made that connection, but you just did. You might have completed the chain of knowledge started long, long ago. Isn't that exciting?”

“No,” the twins said in unison.

“People have said Atlantis was in a lot of places throughout history,” the professor told them. “Everywhere from the Amazonian rainforest to the coast of Spain, and yet it has never yet been found.”

“Because nobody looked to the north.” Dr. Navel smiled. “Everyone was looking for Poseidon's great civilization under the water, but no one looked under ice. No one was looking for Santa Claus.”

“You know the old saying about finding things?” their mother asked. “How they're always in the last place you look? Well, we've looked everywhere else for Atlantis, so why not the North Pole?”

“Lost things are always in the last place you look,” said Celia, “because you wouldn't keep looking for them after you found them.” Celia glanced at Oliver. He nodded. “And that's why, we think, like, just this once, we want to go with you.”

“What?” said their father.

“What?” said their mother.

“Bwak,” said Dennis the chicken.

“Well, like everyone's always telling us”âOliver nodded at Quiâ“there's a prophecy. Visions and greatest explorers and all that.”

“And we figured you'd never find Atlantis without us,” added Celia. “And this way, we can be done. This can be the last place we look.”

Their parents looked at each other, amazed. Never in their wildest dreams did they imagine Oliver and Celia actually wanting to go exploring with them.

“Don't get the wrong idea,” said Celia. “This isn't going to be a regular thing. It's just this once.”

“So that we can all stay together, like a normal family,” said Oliver.

“Even though normal families never have to escape from mobs of goat herders and bloodthirsty pirates in Djibouti,” said Celia. She scowled at Oliver before he could laugh.

“Djibouti.” The professor chuckled under his breath.

Celia sighed. “And when this is over, we want our own TVs in each of our rooms,” she said.

“Big ones,” added Oliver.

“With flat screens.”

Their parents grinned at each other from ear to ear. Their mother reached over and hit a button on the intercom to the pilot.

“Captain,” she said. “Take us north. We're going to the Svalbard archipelago.”

“That's near the North Pole?” asked Celia.

Her mother nodded.

“Did you know that in the North Pole, every direction is south?” their father asked. “Isn't that amazing! When you're at the North Pole, everywhere is below you!”

“Great.” Celia groaned. “Nowhere to go but down.”

Dr. Navel ignored her. He patted her on the head and went with their mother to look over maps.

“How will we find this Atlantis place when we get there?” Qui squished into the seat next to Celia.

“Our parents will figure that out.” Oliver shrugged.

“They've never figured any of this stuff out before.” Celia shook her head. “Why would they start now?”

“So what do you think we should do, if you're such a great explorer?” Oliver asked.

“I didn't say I'm a great explorer,” said Celia. “I just said that we'll probably figure this out before Mom and Dad do, because that's, like, what always happens.”

“Maybe something different will happen this time,” Oliver said. “Maybe they'll save the day and we can just relax.”

“Mom said

we

have to finish this prophecy before we can go home,” said Celia. “Not her. Us.”

“Can I help?” asked Corey.

“Yeah, could you explain the prophecy to us and tell us what to do?” said Oliver. Corey scratched his head but didn't answer. Oliver looked at Qui.

“How would I know?” she said.

“You were in our visions in the Amazon,” said Celia. “You helped guide us.”

“Those were your visions,” Qui said, shaking her head. “I'm not psychic or magic or anything,” she explained. “It's like on your TV. I was just the antenna on the television set, not the show. I helped you pick up the broadcast signal. I'm just a kid like you.”

“Not really like us,” said Oliver.

“I know that that one line from the prophecy,

the greatest explorers shall be the least,

is about us,” said Celia. “We're the least.”

“The least what?” asked Oliver.

“The least whatever. The least old. The least interested. The least adventurous.”

Qui and Corey nodded. No one would disagree with that.

“That also means that we're the greatest,” said Oliver.

“So Santa is and is not Santa, and you are and are not the greatest,” Corey repeated.

“I guess so,” said Celia.

There was a long silence as they considered that possibility. They listened to the loud drone of the airplane engines with wrinkled brows and pursed lips.

Oliver finally broke the quiet with an idea that had just occurred to him.

“Hey, maybe when we're in the Arctic we'll get to ride dogsleds.” Oliver smiled.

Riding on dogsleds across the Svalbard archipelago sounded just like something

Agent Zero

would do. He looked over at Corey, who looked pretty excited too. They high-fived each other. Celia grunted and the boys stopped smiling.

Celia had agreed to go on this adventure, but she had never agreed to enjoy it.

WE TURN THE PAGE

“DON'T TELL ME

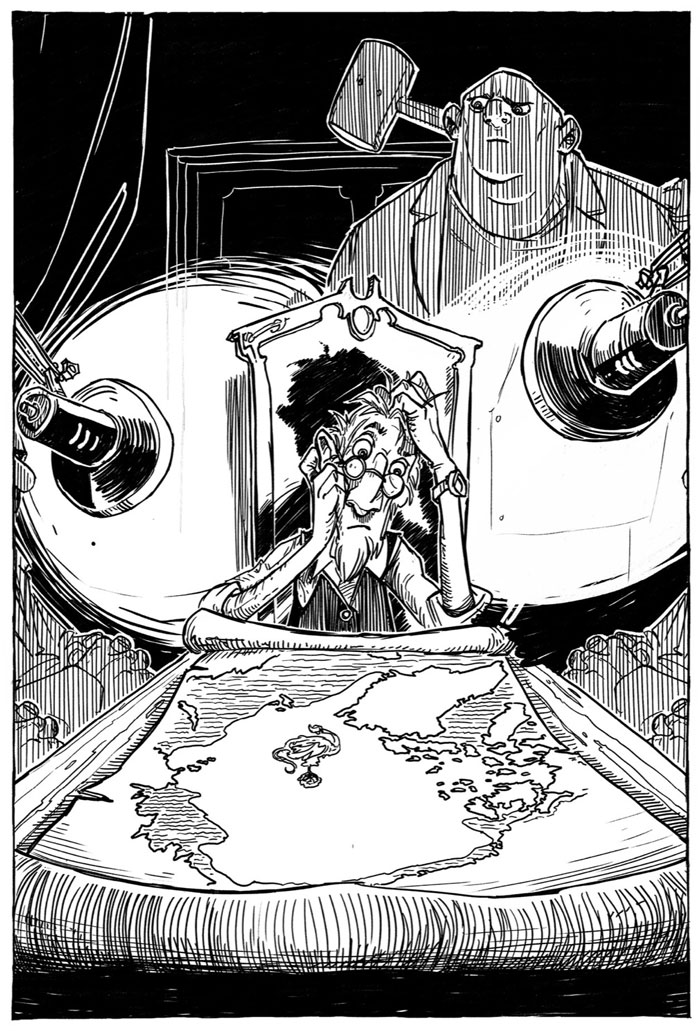

you don't understand. I know you understand because this is perfectly understandable to someone of your understanding!” Sir Edmund slammed his fist down on the long wooden table.

“Uh . . . what?” quivered the explorer at the opposite end of the table, squinting in the bright light that shone into his eyes and not understanding anything the little man had just shouted at him.

The explorer was not tied up or held at the point of a spear or a gun or a weapon of any sort, and yet it should be quite clear to us, by his darting eyes and the nervous tapping of his fingers on the table and the pools of sweat soaking through his shirt jacket, that he was indeed a prisoner. On either side of the table, stern men in dark suits watched the explorer carefully.

“I don't understand what you're asking me,” he squeaked.

“Poppycock!” Sir Edmund slammed his fist on the table again. “Balderdash! Flimflammery!”

“I don't understand that either,” the explorer cried.

“Edmund,” said the only man at the table who was not wearing a suit. He wore a T-shirt and blue jeans and had a baseball cap pulled low over his face. He hardly looked up from his cell phone, on which he was tapping away sending text messages. “Your question was confusing.”

“It's

Sir

Edmund,” Sir Edmund said.

The man stopped tapping on his phone. He, like everyone at the table but the explorer, wore a gold ring engraved with a symbol of a scroll locked in chains, the symbol of the Council, enemies of the Mnemones from time immemorial. He fiddled with the ring but didn't say a word.

The other figures on the Council held their breath, waiting. Sir Edmund's nostrils flared.

“Did I forget to call you sir?” The man in the baseball cap smiled. “Oops.” He shrugged and went back to sending text messages.

“Ahem.” Sir Edmund cleared his throat loudly. “Ahem,” he tried again. No one else spoke. The captive explorer shifted uncomfortably in his chair. All eyes looked toward the man in the baseball cap, who finally looked up from his phone.

“What? Are we done already?” he asked.

“I would appreciate it if you would give these proceedings your full attention,” Sir Edmund told him.

“This is the tenth explorer we've questioned,” the man answered. “None of them know how to read that map of yours, and we're just wasting time. We should be going after the Navels. Unless you're afraid that they'll beat you again.”

“They have never beaten me at anything!” Sir Edmund's face was bright red.

“So your ship sank itself in the Pacific Ocean? The Navels didn't do that?”

“A treacherous giant squid sank my ship,” Sir Edmund answered. “Anyway, I got Plato's map to Atlantis, so I won. The Navels lost.”

“What about getting you kicked out of the Explorers Club?” the man smirked.

“I was not kicked out!” Sir Edmund objected. “I left on purpose. I wanted to start my own club!”

“Oh yes.” The man laughed. “The Gentleman's Adventuring Society . . . an appropriate acronym.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“An acronym is a word formed from the first letters of other words,” the man answered.

“I know what an acronym is, you dolt!” Sir Edmund yelled at him. “But what do you mean by insulting the Gentleman's Adventuring Society!”

“I have nothing against GAS,” the man answered. “I get it all the time.”

The others around the table chuckled behind their hands. Sir Edmund clenched his fists and seethed at them in silence until they were finished. He was their leader, but he knew they were losing patience with him. His power was brought into question at every turn, and if he did not produce results soon he might lose control of the Council for good.

“You!” He pointed down the table at the frightened explorer. “I demand that you answer me now.”

“But I don't remember the question,” the explorer said.

Sir Edmund's eyes nearly popped out of his head in anger.

“My question is this,” he said, trying to keep from shouting again. “Where, in your expert opinion as a scholar of the lost civilization of Atlantis, do you suspect is its true and final location, based on the evidence presented on this map we have placed in front of you?”

The scholar looked nervously at the old map in front of him, with its strangely shaped continents and mysterious ancient Greek writing.

“Well . . . you see . . . I . . . ,” he stammered.

“Enough of this, Edmund.” The man in the baseball cap stood. “He clearly can't read the map! We'll never find Atlantis this way. This so-called scholar is just as useless as all the others.”

“I am not useless!” the scholar objected. “I am an expert on Ice Age archaeology.”

“Whatever that means,” grumbled the man in the baseball cap.

The scholar's face flushed with anger. “It means I have dug up the bones of the saber-toothed tiger and the ancient pliosaur! I have discovered the rune stones of Viking kings and I have had papers published in

Weird Science Magazine

!

”

“I'm sure your parents are very proud of you,” Sir Edmund said, cutting him off.

“I demand to be returned to my research station in Svalbard!”

“Of course,” said Sir Edmund. “Just tell us how to read Plato's map.”

“You know,” the man with the baseball hat said, “

The Daytime Doctor

describes insanity as repeating the same action over and over and expecting a different result.”

“Don't tell me about

The Daytime Doctor.

Television is for lazy minds,” grumbled Sir Edmund.

“Well.” The man stood. “I am not waiting around here any longer. I have important business to attend to.”

“We'll text you if anything important happens,” Sir Edmund sneered sarcastically.

“See that you do.” The man in the baseball cap turned to leave. He stopped in front of the door and turned back to Sir Edmund. “By the way, I heard that the Navels just staged a daring rescue in Djibouti and escaped on a private plane with Corey Brandt. Looks like they've gotten ahead of you . . . again.” He smirked and left the room, slamming the door behind him.

Sir Edmund looked back to the explorer. “Tell me what Plato's map says.”

“How could I possibly read this map?” the explorer whined. “I know nothing about Plato!”

“He was an ancient Greek philosopher,” said Sir Edmund. “He wrote the earliest descriptions we have of the lost city of Atlantis. Surely you must know something about him!”

“No.” The scholar crossed his arms. “Nothing.”

“So you cannot read this map?” One of the well-dressed men leaned forward.

“No one can!” the scholar cried. “There is no key on it! Without a key, we don't know which way is north, or how far these places are supposed to be from each other, or what is a city and what is a mountain. The only thing I recognize is the picture of a dragon on the side.”

“So there are dragons?” Sir Edmund leaned forward.

“No,” said the scholar. “Dragons were often used to decorate maps. They don't mean anything. Or maybe they do. Without a key, the whole map is just a pretty drawing. And anyway, like I said, I don't know anything about Plato's map!”

“You're lying,” said Sir Edmund.

“I am not,” said the scholar.

“You are,” said Sir Edmund.

“I am not,” said the scholar.

They went on like that for several minutes as the rest of the Council snapped their heads back and forth between one end of the table and the other.

“Enough.” Sir Edmund threw his hands in the air in disgust and dropped down onto his chair. All the men of the Council turned to look at him. Because he was a very small man, only the top of his head down to his large red mustache could be seen.

“May I go back to my research station?” the explorer asked. “If I don't return soon, I will be missed. Someone will come looking for me.”

“No.” Sir Edmund didn't even look at the scholar. “You live alone at a research station in the Arctic Circle. No one will even notice you're gone.”

He reached underneath the table and pulled out a small stone tablet with squiggles and lines carved into it. When the scholar saw it, his eyes went wide.

“That's . . . that's the rune stone of Nidhogg!” the scholar cried. “How did you get that?”

“I purchased it from a collector,” said Sir Edmund. “You'd be amazed what you can get when you have millions of dollars to spend.” He nodded to one of his men guarding the door, who came over to the table with a sledgehammer and lifted it high. “Tell me what I want to know, or the stone will be destroyed.”

“You wouldn't!” cried the scholar. “That is a priceless artifact. One of a kind. It tells the myth of Nidhogg the dragon, trapped at the root of the world tree, dreaming of release and revenge.”

“Yes,” said Sir Edmund. “I believe it is also the greatest discovery you have ever made?”

The scholar nodded.

“It'd be shame to see it destroyed,” said Sir Edmund.

The scholar gulped but didn't answer.

Sir Edmund signaled the man with the sledgehammer, who tightened his grip and prepared to pulverize the ancient artifact.

“Wait! Stop!” cried the scholar. “Lord, forgive me. I will tell you what you want to know.”

The scholar took his fingers and turned the map slowly so that the top and bottom became the sides.

Sir Edmund smiled widely. What had looked like a rough coastline became a canyon at the top of the world, a dragon perched neatly inside it, looking down at the world below; what had seemed to be a mysterious landmass took on the rough shape of a very recognizable continent, land and sea and mountain looked strikingly familiar.

“Oh Plato, you clever devil.” Sir Edmund smiled, studying the map. “It's always in the last place you look.” He laughed to himself.

The rest of the Council leaned forward, expectant.

“Gentlemen,” he exhaled. “In his ancient manuscript, Plato described Atlantis as lying âbeyond the Pillars of Hercules.' In his time, that was the end of the known world. Everyone believed he meant the passage from the Mediterranean Sea into the Atlantic Ocean, but if there were more than one set of these pillars, a set in the far north, for example, then he could have been describing a great city in the north, which would now covered by the frozen ice of the Arctic Ocean.”

“Just to be perfectly clear,” one of the men said. “You are saying that Atlantis is somewhere in the Arctic Ocean?”

“I am saying,” Sir Edmund stood and raised his arm like he was posing for a portrait, “that it is at the very top, that frozen land where the Viking warriors had placed their gods, where children dream of Santa Claus, and where Iâ”

“Ahem,” another Council member interrupted Sir Edmund's speech with an exaggerated cough.

“Yes, yes,” grumbled Sir Edmund. “Where

we

will reach our destiny! The North Pole.”

“And what of the Navels?” a man asked. “We cannot have them get in our way again.”

Sir Edmund rolled his eyes. “Don't worry about the Navels. I have a plan for them.” He drew a finger across his throat in a gesture whose meaning was perfectly clear.