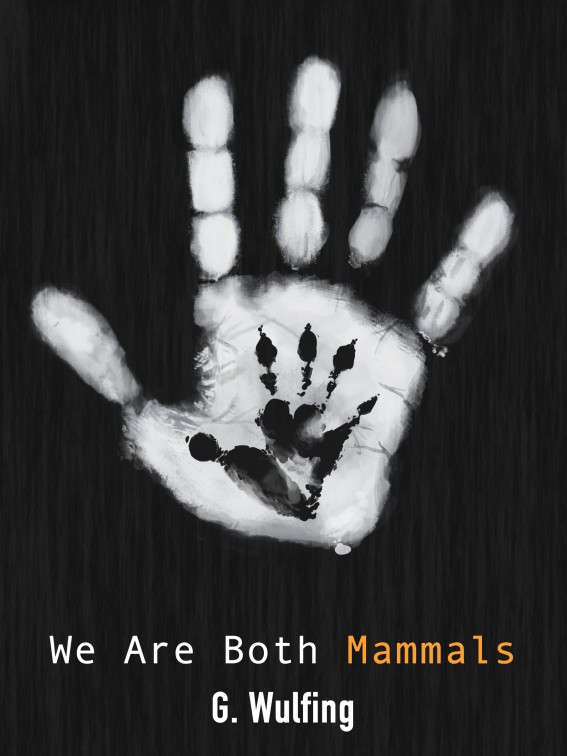

We Are Both Mammals

Read We Are Both Mammals Online

Authors: G. Wulfing

Tags: #short story, #science fiction, #identity, #alien, #hospital, #friendly alien, #suicidal thoughts, #experimental surgery, #recovery from surgery

We Are Both Mammals

Published by G. Wulfing at Smashwords

Copyright 2015 G. Wulfing

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading

this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your

use only, then please return to your favourite ebook retailer and

purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of

this author.

Table of contents:

We Are Both Mammals

Waking was a haze: I cannot say when I first woke or

what happened or what I felt. At some point I opened my eyes; I can

remember doing that, and seeing light from the window of the

clinic, and realising that I was in a hospital bed. It may have

been morning or afternoon; I cannot tell. There were people in the

room with me: the nurses, I believe, and perhaps the surgeon who

had operated on me.

On us.

I know that they spoke to me, but I have no

recollection of what they said. Everything is blurred and vague in

these memories. At some point, I woke up more coherent, and found

that there were no tubes in my mouth nor an oxygen mask on my face.

Presumably this means that I was conscious of those things being

there at some earlier point, but I don’t remember them.

“

Oh, you’re waking up,”

remarked a kindly female voice. My whole body ached dully. I think

I asked where I was and what had happened. The nurse – she of

the kindly voice – informed me that I had undergone surgery. I

remember nothing further.

The next memory is more vivid: of waking

again, and asking where I was and what had happened. A nurse

– possibly the same one, I have no idea – informed me

that I had undergone surgery. I processed this, and asked again,

somewhat dazedly, what had happened. The nurse told me that I had

been in an accident. Slowly, she explained that I had sustained

severe injuries to my internal organs, and that I had undergone

life-saving surgery.

The third time I remember waking up, I felt

fear. Previously I had been too dazed and bewildered to feel much

of anything except some anxiety, but the nurses had sounded so

reassuring that my dozy brain had subsided back into

unconsciousness without experiencing much arousal; this time, my

body seemed to feel that something was wrong. The dull aching in my

body also felt more intense: I was aware of what felt like bruising

and swelling, seemingly throughout my body, and vague pains that

seemed like they were screened off, or coming from underwater,

somehow; not immediate, but still very present in my body. I could

only breathe shallowly, and I was not sure why.

“

What happened?” I

demanded, feebly, of the nurse in the room. I could now see the

room more clearly: it had light blue walls, a couple of doorways

leading off into more brightly-lit areas, and a couple of white

things that might have been boxy machines, or furniture like chests

of drawers, positioned about the room. The lighting was somewhat

dim.

“

You’ve had surgery,” the

nurse replied, approaching the bed. He was dark-skinned, and wore a

pale blue uniform.

“

Why?” I asked anxiously,

not remembering the previous explanation I had received.

“

You were in an accident,”

he said simply.

“

Why?” I croaked stupidly,

suddenly feeling that my throat was rasping and dry.

“

Would you like a drink of

water?” the nurse offered.

I whispered, “Yes”, and there was a faint

humming as he made part of the hospital bed tilt upwards so that my

head and torso were raised slightly and I could drink. As the bed

moved, I registered that my ribs and midriff, from beneath the

pectorals, seemed to be covered in bandages and dressings. My fuzzy

mind reasoned that maybe that bandaging was the reason why I could

not seem to breathe properly.

I could only manage a mouthful from the

disposable cup that he held to my mouth. The effort required seemed

enormous, and exhausting. I felt weak and drained; weaker than I

had ever felt in my life. I seemed to doze after that.

I woke several times in the next twenty-four

hours: I know this because there was an analogue clock on the light

blue wall in front of me, above one of the doorways, and each time

I woke I had the feeling that I had not slept long. The wakings all

blur, however. At some point I discovered that there was a drip

inserted into the back of my left hand. A nurse told me that there

was a pad near my right hand, with electrical cords leading off it,

which I could press if I needed anything, and a couple of times I

pressed it to ask for water. My throat was so dry. I was thirsty,

but I was glad of that, in a way; it was somehow good to feel

something definite, something other than vague pains and

bewilderment and grogginess. My thirst reassured me that I was

alive. Sometimes, half awake, I would hear calm, quiet voices in

the room, but they didn’t seem to be talking to me.

The next thing I remember with any degree of

clarity is that the clock on the wall read five o’clock, and I

could tell by the gloom that it was early in the morning. I

blinked, feeling more awake than before, and pressed the pad under

my hand.

In a moment a pair of nurses arrived, both

female, wearing pale blue uniforms, and they seemed vaguely

familiar somehow. They put on a dim light, raised the upper part of

the bed a little, and helped me to drink. There was a cabinet at my

left that held the disposable cup from which I had been

drinking.

As one of the nurses, standing at my left,

helped me to drink, I realised that the other was on the other side

of the large bed, on my right, doing something. As my brain cleared

a little more, I looked sluggishly in that direction, and realised

that there was another patient in the bed with me: a thurga.

For an instant my drug-addled brain thought

it was an animal, as thurga-a do resemble brushtail possums in many

ways, though they have longer limbs and are the size of a large

domestic cat; and it was mostly covered by the bedclothes, as I

was, as it lay on its back over a metre away from me. Its furry,

dark brown arms, with their hands like a rat’s forepaws, lay on the

sheets that reached to its chest. As the creature’s bright dark

eyes looked back at me from its dark-furred face, I recognised it

as a thurga: a native of the planet on which I was living and

working.

“

Daniel,” said the nurse

on my left, very gently, “have you met Toro-a-Ba?”

In that instant, a curious and terrifying

thing happened. It was as though my brain realised long before I

did that something was horribly wrong. Whether it was the nurse’s

tones or the puzzling sight of the thurga sharing my hospital bed

or something else, I do not know; but a sick chill gripped my

heart. I stared stupidly at the thurga, which held my gaze.

“

No,” I murmured, not

understanding why I felt such trepidation.

“

Daniel, you and Toro-a-Ba

have undergone the same surgery.”

“

Oh,” I mumbled, wondering

vaguely why the thurga’s surgery was relevant to mine.

“

Hello, Daniel,” the

thurga said to me softly, in English, and there was what seemed

like great tenderness in its voice, almost as though it knew me

well. Something about this seemed very wrong to me, but I could not

understand what. Perhaps I was supposed to know this thurga. To a

human, many thurga-a look very similar, so perhaps I did know this

one and simply didn’t recognise it, or something … My head felt so

muzzy and bewildered …

“

Hello,” I mumbled blankly

in reply, still regarding the thurga.

But I was weary already, just from being

awake, so I rolled my head back to its normal position of looking

straight ahead, and my eyes closed almost without my command, and

drowsiness subsumed me. I barely felt the hospital bed being

lowered gently back into its almost-horizontal position beneath

me.

And even as I drifted to welcome sleep,

something in the back of my mind squirmed uneasily.

When I woke again, it was full

daylight. A large window on the left side of the room had its

curtains drawn back to let light into the room, and someone in a

white coat was present with two nurses in their pale blue uniforms.

As I was lucid enough to speak and be spoken to, my bed was raised

slightly, and the new person stood at the left of my bed and

introduced herself: Sarah Fong, who informed me that she was one of

the primary surgeons who had worked on me, and a specialist in

synthetic organs, transplants, and the human digestive system. She

was petite, dark haired, and seemed to be of Asian descent. She

wore casual business clothes underneath her white coat.

“We

were working on you for a good twenty-five hours,” she told me

pleasantly. “I’ve been checking you over every day since then, and

everything seems to be going smoothly. You’re stable, and that’s

excellent. At this stage, that’s all we ask.”

I had so many questions that I did not know

where to begin. So once again I repeated, “What happened?”

“

You were in an

accident.”

Yes, I knew that, but: “What kind of

accident?”

“

There was a malfunction

in the laboratory where you work, and you fell under some machinery

that crushed your abdomen. I’m not sure exactly what happened, but

no doubt your colleagues and the other people who were present can

explain it to you later.” Surgeon Fong paused for a moment,

regarding my abdomen. I was watching her face, and I saw her eyes

flick to the thurga that lay beyond arm’s reach beside me. “You

suffered massive trauma to both intestines, your liver, kidneys,

gall bladder, and stomach – pretty much your whole digestive

system,” she told me frankly. “You also had five broken ribs. Your

major systems were all failing as a result of the trauma, and you

would not have survived if we had not performed this surgery.

Thankfully your spleen was intact, otherwise we wouldn’t have been

able to save you.”

I tried to take all this in. My breathing

was still shallow and awkward, and it was difficult to concentrate.

The surgeon paused again, and turned to the two nurses in the room.

In a low voice I heard her ask them, “Has he realised?”, to which

both of them shook their heads.

Surgeon Fong consulted a clipboard for a

moment. Then she turned to me again. “Have you met Toro-a-Ba?” she

asked, almost offhandedly; a little awkwardly, even, without quite

making eye contact.

I nodded gingerly, not sure why that should

be important. I still did not know why a thurga was in the hospital

bed with me, but it was hardly the most pressing of my

concerns.

“

He underwent

– similar surgery to yours,” Surgeon Fong said. She cleared

her throat, glanced at the nurses, and gestured toward the

bedclothes, leaning over me a little. “Perhaps now would be … er

…?” she murmured.

The nurses nodded, and moved forward. The

bedclothes were peeled back, and I saw that it was not just my ribs

and midriff that were bandaged: my entire abdomen was covered in

various bandages, dressings and tubes. I gulped, and gave a slight

gasp of distress, feeling light-headed with the shock.

From my sternum to my thighs, the skin that

was not hidden under bandages was discoloured with bruising. The

flesh of my torso was swollen and puffy. A dozen or more slim,

transparent flexible hoses were embedded in my skin, leading off my

body, bearing assorted fluids – clear, bloody, yellowish red, and

even greenish brown; they were held in place by adhesive dressings

or visible black stitches. Many were looped around to make sure

they entered my body at the correct angle, and the loops were

bandaged in place. I was hideous. I gazed at the infestation of

dressings and hoses in dismay and dizzy bewilderment, feeling sick,

wishing that someone would explain why this had happened and

whether I would ever recover to full strength. Would I be all

right? Were my organs all still where they should be? What exactly

had been done to me?

“

Are you all right,

Daniel?”

I looked up groggily to see Surgeon Fong

studying my face, probably noting the fact that I was feeling

nauseated. I gave a couple of small nods, though ‘all right’ was

most definitely not what I felt.

“

It looks a bit of a mess,

doesn’t it,” one of the nurses supplied sympathetically.