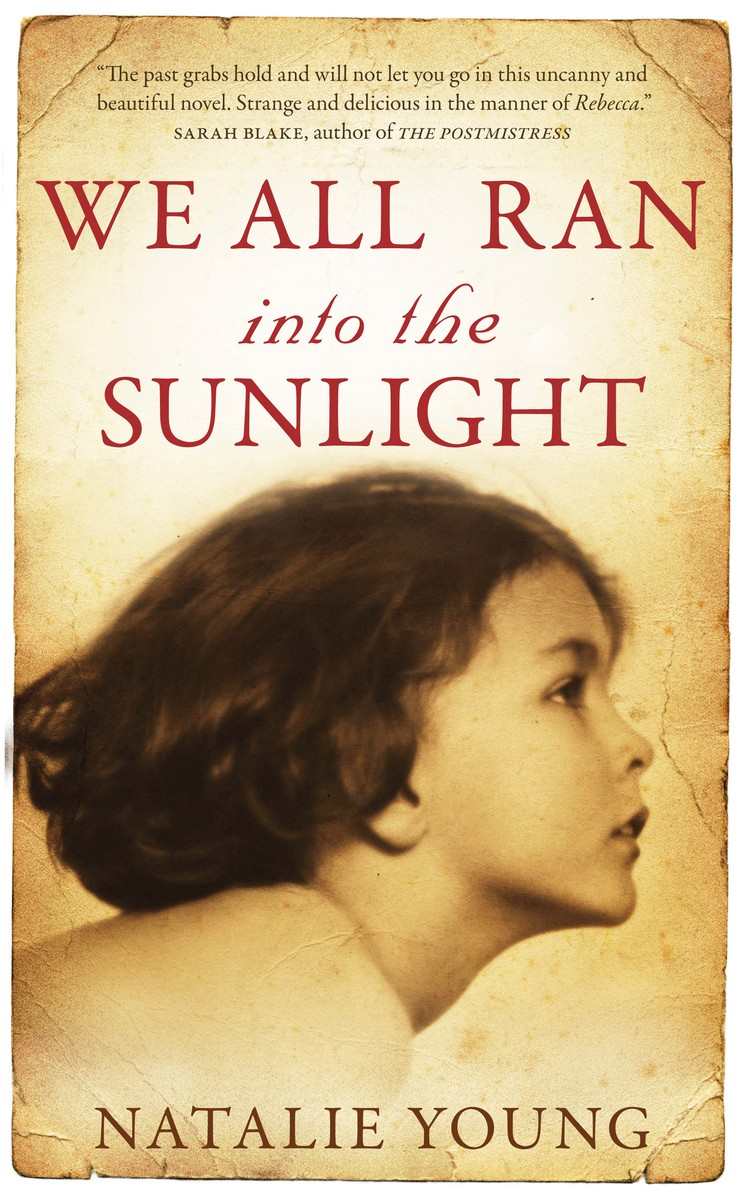

We All Ran into the Sunlight

Read We All Ran into the Sunlight Online

Authors: Natalie Young

into the

SUNLIGHT

NATALIE YOUNG

For Aurea Carpenter

Je dis: ma Mère.

Et c’est à vous que je pense, ô Maison

Maison des beaux étés obscurs de mon enfance.

I say: Mother.

And my thoughts are of you, oh House

House of the lovely dark summers of my childhood.

Oscar Milosz

ROLOGUE

From the middle of June that summer the heat went up into the high thirties and stayed there, so that nothing much happened in the village and nobody moved. People sat in their chairs with their mouths hanging open. Most of the time they slept. In the village shop, the water

supplies

and the ice creams ran out long before the delivery came on a Monday afternoon. Only right at the end of August, when the holidays were over and the motorways clogged with cars going home, did a wind pick up off the sea. It came in quite violently; clearing the heat out of the sky and making the sea go a deep blue far out. Then it rose over the sand dunes and the dry grasses on the

floodplain

. It moved through the swinging doors of the

roadside

cafés that lined the motorway on its final stretch to the Spanish border, until it came to where the vineyards were, some twenty miles from the coast, which was where the land began to rise into the hills.

The wind brought with it relief, and a kind of foreboding. In the village the children felt it. Even the cicadas might have felt it for it went very quiet all of a sudden as if, on the plane trees lining the main road, they had ceased their sucking of the sap and taken a pause, while the leaves turned in on each other with

whispering

relief and the rooks, startled out of their slumber, crashed around madly then stretched their wings and flew, croaking resentfully, at the sun.

There was only one road into Canas then, and you had to turn round in the square and drive out again with the church on your left this time and the east wall of the chateau rising up to your right. You could sit at the café, at a table under the lime trees, and that wall would dominate the square, blocking the afternoon sun. It was like a medieval fort, with only one window near the top. But if the shutters were open, which they often were in those days, and the light was right, you could look up through the balcony railings and see in through the old panes to the giant rose on the ceiling of Lucie Borja’s

bedroom

.

Things changed that August day. Things changed in a way that no one would want to talk about in years to come. There was the heat, and then the air coming in like that, lifting the dust from the ground in the chateau courtyard, and nuzzling up to the front walls.

Lucie withdrew from the balcony and into the quiet of her bedroom. When her eyes had adjusted to the light she saw that Daniel was there – barefoot and silent; he was standing in the doorway.

‘Come in,’ she whispered and he stepped forward with the birthday present in his hand.

‘It’s not much,’ he said. ‘It’s not as if there’s any choice here though.’ He stood beside her while she untied the ribbon and counted the almonds out on the bed. He’d tied them in a muslin cloth using a sprig of olive he’d got from the courtyard, and Lucie made a fuss of this, bending over with enthusiasm and attaching all kinds of importance to what was never really there.

‘Chocolates would have melted,’ said Daniel. He was nineteen. He was wiry, and dark-skinned and his eyes were a pale greeny blue, like pebbles of washed-up glass. His mother gazed up at him.

‘Happy birthday,’ he said, but his voice had no life in it. ‘I’ve got to go because Sylvie’s coming to help us

prepare

.’

‘That’s fine,’ said Lucie, with her watery eyes. ‘But will she stay for the party? And is Frederic coming?’

‘Later,’ Daniel said. ‘He’s up on the heath at the

moment

, with the flying club. They’ve got a sea plane coming in up there for fuel.’

‘Are the fires still burning on the hills, Daniel?’

‘Yes, Maman,’ he said, quietly, ‘there’s an arsonist up there. He’s setting fires on the hills, and now there’s a wind picking up. It will only get worse through the

afternoon

.’

She reached for his hand and held it; rubbing the smooth skin with her thumb. ‘It won’t come for us though, Daniel. Nothing will come to disturb us on this night. Your poor Maman is getting old. But tonight we will eat all of your favourite things under the olive trees in the courtyard.’

‘Me, Frederic and Sylvie won’t stay for the whole meal,’ said Daniel, backing away towards the door.

‘Of course. I knew that. When does Frederic leave?’

‘Monday,’ said Daniel.

Two days, thought Lucie. ‘I imagine that Sylvie will miss her brother when he goes,’ she said. ‘And you too.’

‘Happy birthday,’ he said.

‘Thank you, my love.’ Lucie smiled at her son’s back as he turned to go.

And then he was gone, walking quickly in the corridor and down the wide stairs on the hard pads of his feet.

‘Am I too early?’ said Sylvie as she reached where Daniel was standing outside with one leg up against the wall. In the courtyard it was bright; intensely white, and Sylvie, in a floral dress, put her hand up to shield her eyes.

‘It doesn’t matter much,’ he said. ‘Early or late, it makes no difference to anyone.’

He shrugged and ground his cigarette into the step. Sylvie laughed. She had braces, which she did her best to hide, but her freckled face, in its corral of wild black hair, was almost pretty.

‘I don’t mean it doesn’t matter much to me,’ said Daniel, touching her on the shoulder to make her feel more at ease. ‘I just mean it doesn’t matter much to this place. Nothing makes any difference here.’

‘Except this,’ said Sylvie, taking the plastic wallet from the bag slung across her hip.

‘You went to Béziers,’ he said, excitedly.

‘It’s really good stuff. It was easy.’

‘Same guy?’

‘Same as always. Nice guy.’

‘Did your dad notice you’d taken the car?’

Sylvie blushed, shook her hair forward, and then busied herself lighting a cigarette which she held out far from her body.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ Daniel grinned.

‘It doesn’t matter at all,’ she said. ‘Nothing does. Right?’

He kissed her once, very quickly, on the cheek. Then he drew a green stem of marijuana from inside the wallet and held it under his nose.

‘Mother of Christ,’ he whispered, carefully putting it back into the pouch. It was how they’d got through this summer, he and his two friends from the village,

smoking

pot in the garden room across the courtyard from the chateau. Week after week, singing and laughing in there, rolling up smoke after smoke so the nights could go on, leading them on through the games and the psychedelic frogs towards the dry light of dawn.

‘You ok, Daniel?’

‘I’m fine,’ he said, and he swallowed, his cheeks sucked right in as he put the wallet of grass in the pocket of his shorts. In his other pocket he flicked his lighter on and off and after a while Sylvie put her hand into his.

‘You’re going to miss him. We all are. It won’t be the same.’

Daniel laughed coldly.

‘You are going to miss him, Daniel?’

‘Huh!’ he muttered, taking his hand back and kicking the stones at his feet. ‘He shouldn’t be joining the bloody army. I wouldn’t go, not for anything. I don’t understand Frederic. Why he just takes these things lying down.’

‘That’s not how it was… he

wants

to go.’

‘It’s fine,’ said Daniel, and he stuck his jaw forward and looked out across the vineyard. There was silence then. The heat came down. The cicadas were shrill in the grass. Sylvie was squinting as she looked at him.

‘Is Arnaud here?’

‘He went to town in the car.’

‘Let’s go see if your mother needs help,’ she said,

pulling

the pocket of his shorts playfully, and then she walked ahead of him, grinning back at his solemn face.

By seven the light was pink-tinted and the midges were out and dancing around their heads. Lucie Borja stood on the steps with her ankles pressed together in little cream shoes. Daniel and Sylvie were carrying the dining-room table through the front doors and down to the olive trees, Daniel with his end of the table behind his back, Sylvie struggling as she came behind.

They bent beneath the trees and placed the table down. Sylvie flopped down over it. Lucie took in a breath of air between her teeth. It was right to bring the table outside. There was more air in the courtyard than round the back in the garden; it was a perfect fit between the four trees and soon they would hang the Chinese lanterns.

She watched Daniel standing back now, a little way off, looking up to the road that wound up through the pine trees onto the heath. On a grassy plateau up there was a runway, a turning field and a small hangar for the planes used by the flying club. The runway went from one end of the plateau to the other, and Frederic was up there cleaning the planes, helping out with the fuel. It was manly work and Lucie knew that Daniel wanted to be up there with him, not here with his mother. She wondered again about his restlessness and agitation. He was dreaming, perhaps plotting his own escape, and she felt the tears prick –

always

tears on a birthday; she was much too sentimental – so she smoothed the linen on her hips and walked down the steps towards them.

‘Oh, Daniel, Sylvie,’ she croaked, ‘how beautiful this looks. We should take a picture, no? Shall we light the lanterns, Daniel,

chéri

?’

‘After dark,’ he said, without looking at her, and Lucie felt the snub and that same old cold feeling, which was what propelled her from the edge of the table, walking towards him when her ankle gave on the bald patch of ground and the soft outer edge of her foot caved in. The fall wasn’t a bad one, but Daniel didn’t go to his mother, and the sound she made was a sound like no other sound he had heard. Only a child, only a baby, made a sound like that, thought Daniel, clapping his hands over his ears as he ran from his mother and across the courtyard into the garden room.

At three in the morning, Lucie’s eyes flicked open. She lay very still. Then she flexed the ankle and felt to the end of the bed for her dressing gown.

In the room next door, her husband was snoring, his spirit sunk in the food and drink from the party. It would take an age to wake him. She kept close to the wall,

clutching

the handrail on the stairs. She couldn’t smell the fire but she knew it was there, feeding like a lion in a corner of the kitchen. She moved quickly, talking to herself as she went. So they may have forgotten to check the gas rings; something might have been left on, some faulty

electrical

application. You could never trust the electrics; the place was wired in a haphazard way and the mice chewed through everything. But the fire wasn’t in the kitchen, and Lucie had known that before she had even left her room. She came to the bottom of the stairs, and hobbled

slightly

across the hall, folding her dressing gown across her chest.