Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering (13 page)

Read Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering Online

Authors: John W. Dower

The

machinery

of modernityâboth literal and figurativeâwas of absorbing interest in 1930s Japan. The rapid technological and industrial change that had enabled Japan to leap from feudal seclusion to a place among the great powers of the world within a mere half century was manifest in more than military prowess. In the wake of World War I and the massive Kanto earthquake of 1923 (which prompted an enormous construction boom along more modern lines in the Tokyo-Yokohama area), Western-style modernism was visible wherever one looked. Tall buildings arose in the cities. Automobiles appeared on the streets. Trains crisscrossed the land. Airplanes dotted the sky. A subway rumbled through the bowels of Tokyo (

Fig. 3-6

). Western-style fashionsâmusic, clothing, food, movies, even “free love”âcaptivated a new urban bourgeoisie.

At the same time, it was also indisputable that such creative modernization went hand in hand with technocratic “rationalization” and the mobilization of hitherto unimaginable violence. World War I had taught military planners throughout the world that future victories would depend on the capability of mobilizing

every aspect of society behind the war effortânot only government, industry, finance, and armies and navies, but the support of the entire population as well.

Psychological

mobilization, drawing upon all the resources of modern means of communication, was as important as weaponry in waging all-out war.

Fig. 3-6.

Nagajuban

, “Modernity” (detail). Japan, ca. 1930. Printed muslin; 13 ¾'' x 19 ¼''. Collection Tanaka Yoku, Tokyo. Courtesy of Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture; New York. Photographer: Nakagawa Tadaaki/Artec Studio.

Reconstruction of the Tokyo-Yokohama area along more modern lines after the devastating Kant

Å

earthquake of 1923 was reflected in everything from department stores and subways to electric and telephone lines crisscrossing city streets.

By the mid-1930s, such “total war” planning had become extremely influential in Japan, invariably framed in terms that strengthened the role and authority of the state. Former Marxists joined right-wing ideologues in calling for some form of state socialism or national socialism. Iconoclastic cadres of new bureaucrats (

shin kanry

Å

) and reform bureaucrats (

kakushin kanry

Å

) moved into positions of influence in key ministries. A score or so giant industrial conglomerates emerged under the generic name “new combines” (

shinko zaibatsu

), distinguished by their close ties with the military, by their concentration in military-related enterprises, and often by their close involvement with the industrial development of Manchukuo. In certain critical sectors, so-called national policy companies (

kokusakugaisha

) were created to forge a formal mix of public and private capital and management.

None of this took place without opposition. Factionalism was intense in military as well as civilian circles, and 1930s Japan reeled under the impact of assassinations and even (in 1936) a serious attempted coup d'etat led by young Army officers. But ultimately the hard-nosed militarists and reform bureaucrats had their way. The Peace-Preservation legislation of the 1920s was enforced with increasing severity to repress not only the dangerous thoughts of those deemed too liberal and supportive of Anglo-American ideals, but also those deemed to have moved too far toward the radical, terrorist right.

The takeover of Manchuria that began in 1931 became an ideological touchstone and signpost for many of these developments. While Chinese diplomats denounced Japan's seizure of China's “three eastern provinces” and the League of Nations formally condemned this disturbance of the international status quo, the Japanese public was persuaded that their country had embarked

on a great mission. “Manchukuo as Ideology” became yet one more uplifting catchphrase. In print media, propaganda posters, films, and songs, the new puppet state was presented not merely as a bountiful, almost utopian land to which poor Japanese families could emigrate, but also as a perfect pilot project for the realization of state socialism. In Manchukuo, the new bureaucrats and their reformist military counterparts declared, it would be possible to create a model state free of the exploitation and instability of the

capitalist system that had plunged the world into depression and chaos. Simultaneously, racial harmony would be promotedâso unlike the intolerant world of white, yellow, and red perils.

Fig. 3-7.

Haori

with “Mantetsu”

haura

. Japan, early 1930s.

Haori

: black silk; 41 ½'' x 51''.

Haura: y

Å«

zen

-dyed silk; 22''x 21 ¾''. Collection Tanaka Yoku, Tokyo. Courtesy of Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture; New York. Photographer: Nakagawa Tadaaki/Artec Studio.

The textile rendering of a roaring locomotive was based on posters advertising the South Manchurian Railway, which lay at the heart of Japan's neo-colonial presence north of the Great Wall of China. Such images elicited pride in Japan's technological prowess, as well as heady excitement about the pioneering challenge of developing the new puppet state of Manchukuo.

Fig. 3-8. Nakamura Sh

Å«

k

Å

,

The Great Victory of Japanese Warships off Haiyang Island

. Japan, 1894. Woodblock print. Photograph © 2011 Collection Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Anonymous Gift (23.288â90).

In this typically dramatic celebration of Japanese naval prowess in the first Sino-Japanese War, the majestic battleship

Matsushima

sinks a Chinese warship. Intrepid sailors man small craft in the turbulent waves, while other large Japanese vessels loom in the background.

The raw, expansive beauty of Manchuria enhanced its great appeal. A cadre of distinguished professional photographers sent back memorable, brooding images in the mode of social realism. Travel agencies and the powerful South Manchurian Railway Company churned out colorful posters inviting tourists to ride the great trains across this new frontier. Children's culture was permeated with the same image of an inviting land ripe for development (

Fig. 3-7

).

9

Such pictures of Manchukuo as a place of great drama, great opportunity, and great machines were part and parcel of a larger national pride at the remarkable development of the Japanese economy. The turn-of-the-century victories over China and Russia represented the first great demonstration of this transformation from

an agrarian to an industrial society. Manchukuo and the total-war mobilization of the 1930s provided an even more spectacular display, and few adult Japanese could fail to be impressed by the speed and scale of this industrial and technological change. A man or woman fifteen years old when Japan defeated Russia in 1905, for example, would have been only forty-one when the Manchurian Incident occurredâand only fifty-one when, in 1941, Japan took on the world.

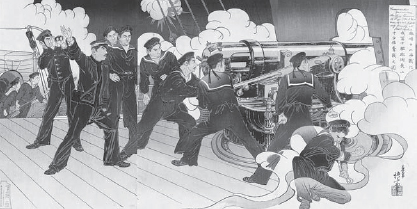

Fig. 3-9. Migita Toshihide,

Chief Gunner of Our Ship

Fuji

Fights Fiercely in the Naval Battle at the Entrance to Port Authur

. Japan, 1904. Woodblock print. Photograph © 2011 Collection Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Jean S. and Frederic A. Scharf Collection (2000.75).

This illustration from the Russo-Japanese War recycles the formulaic depiction of disciplined fighting men manning the most up-to-date military technology that first appeared ten years earlier in woodblock prints depicting the Sino-Japanese War.

Many of the patterns and conventions that characterized war imagery in the 1930s and early 1940s were actually established in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894â95. Although photojournalism was becoming widespread in the United States and Europe by then, in Japan the most dramatic depictions of this earlier war against China took the form of popular woodblock prints. In the course of the ten months this conflict lasted, a small coterie of woodblock artists churned out an estimated three thousand brightly colored

battle scenes. Many of these stylized images of heroic struggle were recycled in the war against Russia ten years later, even as the woodblock medium was fading away before the advent of photography and other forms of illustration in Japan. And they returned, transmogrified, in the fifteen-year war. The warships were stupendous. The artillery was huge. The emperor's fighting men were not merely stalwart and resolute, but tall and square-jawed and almost perfectly Western in their dress and facial hairâclearly much closer to the Russians than to the pumpkin-headed, pigtailed, grotesquely garbed Chinese (Figs. 3-8 and 3-9).

Modern economic growth made these turn-of-the-century victories possible (plus large loans from New York and London where fighting the Russians was concerned). And, indeed, that earliest stage of industrialization had been deliberately skewed to promote heavy state involvement in strategic military-related industries. Nonetheless, the early-twentieth-century economy remained fundamentally concentrated in textiles and light industry, with female workers constituting more than half the factory workforce. Japanese capitalism was still at a relatively rudimentary stage.

Beginning a mere decade after the Russo-Japanese War, World War I sparked a war boom in Japan that saw great advances in factory production and the expansion of a male urban working class, as well as the consolidation of the huge “old”

zaibatsu

oligopolies (Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda). It was not until the 1930s, however, that Japan actually experienced what economists refer to as its “second industrial revolution,” marked by rapid and autonomous development in heavy and chemical industries. Mobilization for total war not only helped pull Japan out of the depression. It propelled the nation to entirely new levels of technological accomplishment.

10

In a context of actual war, these developments were spectacular to behold. All modern nations take pride in flexing their industrial muscle; and at a time when photography and then cinema were becoming accessible to mass audiences, a peculiar fascination was reserved for images of assembly lines and heavy machinery and

remarkable vehicles. Add to this the furniture of modern warâmachine guns and heavy artillery, battleships, submarines, fighter planes, tanksâand the impact could easily become mesmerizing.