Water for Elephants (5 page)

Read Water for Elephants Online

Authors: Sara Gruen

The stream is a couple of feet wide at most. It runs along the tree line at the far side of the clearing and then cuts off into the woods. I peel off my shoes and socks and sit at its edge.

When I first submerge my feet in the frigid water, they hurt so badly I yank them out again. I persist, dunking them for longer and longer periods, until the cold finally numbs my blisters. I rest my soles against the rocky bottom and let the water wriggle between my toes. Eventually the cold causes its own ache, and I lie back on the bank, resting my head on a flat stone while my feet dry.

A coyote howls in the distance, a sound both lonely and familiar, and I sigh, allowing my eyes to close. When it is answered by a yipping only a few dozen yards to my left, I sit forward abruptly.

The faraway coyote howls again and this time is answered by a train

whistle. I pull on my socks and shoes and rise, staring at the edge of the clearing.

The train is closer now, rattling and thumping toward me:

CHUNK

-a-chunk-a-chunk-a-chunk-a,

CHUNK

-a-chunk-a-chunk-a-chunk-a,

CHUNK

-a-chunk-a-chunk-a-chunk-a

. . .

I wipe my hands on my thighs and walk toward the track, stopping a few yards short. The acrid stink of oil fills my nose. The whistle shrieks again—

TWE-E-E-E-E-E-E-E-E-E-E—

A massive engine explodes around the bend and barrels past, so huge and so close I’m hit by a wall of wind. It churns out rolling clouds of billowing smoke, a fat black rope that coils over the cars behind it. The sight, the sound, the stink are too much. I watch, stunned, as half a dozen flat cars whoosh by, loaded with what look like wagons, although I can’t quite make them out because the moon has gone behind a cloud.

I snap out of my stupor. There are people on that train. It matters not a whit where it’s going because wherever it is, it’s away from coyotes and toward civilization, food, possible employment—maybe even a ticket back to Ithaca, although I haven’t a cent to my name and no reason to think they’d take me back. And what if they will? There is no home to return to, no practice to join.

More flat cars pass, loaded with what look like telephone poles. I look behind them, straining to see what follows. The moon slips out for a second, shining its bluish light on what might be freight cars.

I start running, moving the same direction as the train. My feet slip in the sloping gravel—it’s like running in sand, and I overcompensate by pitching forward. I stumble, flailing and trying to regain my balance before any part of me comes between the huge steel wheels and the track.

I recover and pick up speed, scanning each car for something to grab on to. Three flash by, locked up tight. They’re followed by stock cars. Their doors are open but filled by the exposed tail ends of horses. This is so odd I take note, even though I’m running beside a moving train in the middle of nowhere.

I slow to a jog and finally stop. Winded and very nearly hopeless, I turn my head. There’s an open door three cars behind me.

I lunge forward again, counting as they pass.

One, two, three—

I reach for the iron grab bar and fling myself upward. My left foot and elbow hit first, and then my chin, which smashes onto the metal edging. I cling tightly with all three. The noise is deafening, and my jawbone bangs rhythmically on the iron edging. I smell either blood or rust and wonder briefly if I’ve destroyed my teeth before realizing the point is in serious danger of becoming moot—I’m balanced perilously on the edge of the doorway with my right leg pointed at the undercarriage. With my right hand I cling to the grab bar. With my left I claw the floorboards so desperately the wood peels off, under my nails. I’m losing purchase—I have almost no tread on my shoes and my left foot slides in short jerks toward the door. My right leg now dangles so far under the train I’m sure I’m going to lose it. I brace for it even, squeezing my eyes shut and clenching my teeth.

After a couple of seconds, I realize I’m still intact. I open my eyes and weigh my options. There are only two choices here, and since there’s no dismounting without going under the train, I count to three and buck upward with everything I’ve got. I manage to get my left knee up over the edge. Using foot, knee, chin, elbow, and fingernails, I scrape my way inside and collapse on the floor. I lie panting, utterly spent.

Then I realize I’m facing a dim light. I jerk upright on my elbow.

Four men are sitting on rough burlap feed sacks, playing cards by the light of a kerosene lantern. One of them, a shrunken old man with stubble and a hollow face, has an earthenware jug tipped up to his lips. In his surprise, he seems to have forgotten to put it back down. He does so now and wipes his mouth with the back of his sleeve.

“Well, well, well,” he says slowly. “What have we here?”

Two of the men sit perfectly still, staring at me over the top of fanned cards. The fourth climbs to his feet and steps forward.

He is a hulking brute with a thick black beard. His clothes are filthy,

and the brim of his hat looks like someone has taken a bite out of it. I scramble to my feet and stumble backward, only to find that there’s nowhere to go. I twist my head around and discover that I’m up against one of a great many bundles of canvas.

When I turn back, the man is in my face, his breath rank with alcohol. “We don’t got room for no bums on this train, brother. You can git right back off.”

“Now hold on, Blackie,” says the old man with the jug. “Don’t go doin’ nothing rash now, you hear?”

“Rash nothin’,” says Blackie, reaching for my collar. I swat his arm away. He reaches with his other hand and I swing up to stop him. The bones in our forearms meet with a crack.

“Woohoo”

cackles the old man. “Watch yourself, pal. Don’t you go messin’ with Blackie.”

“It seems to me maybe Blackie’s messing with me,” I shout, blocking another blow.

Blackie lunges. I fall onto a roll of canvas, and before my head even hits I’m yanked forward again. A moment later, my right arm is twisted behind my back, my feet hang over the edge of the open door, and I’m facing a line of trees that passes altogether too quickly.

“Blackie,” barks the old guy. “Blackie! Let ’im go. Let ’im go, I tell ya, and on the inside of the train, too!”

Blackie yanks my arm up toward the nape of my neck and shakes me.

“Blackie, I’m tellin’ ya!” shouts the old man. “We don’t need no trouble. Let ’im go!”

Blackie dangles me a little further out the door, then pivots and tosses me across the rolls of canvas. He returns to the other men, snatches the earthenware jug, and then passes right by me, climbing over the canvas and retreating to the far corner of the car. I watch him closely, rubbing my wrenched arm.

“Don’t be sore, kid,” says the old man. “Throwing people off trains is one of the perks of Blackie’s job, and he ain’t got to do it in a while. Here,” he says, patting the floor with the flat of his hand. “Come on over here.”

I shoot another glance at Blackie.

“Come on now,” says the old man. “Don’t be shy. Blackie’s gonna behave now, ain’t you, Blackie?”

Blackie grunts and takes a swig.

I rise and move cautiously toward the others.

The old man sticks his right hand up at me. I hesitate and then take it.

“I’m Camel,” he says. “And this here’s Grady. That’s Bill. I believe you’ve already made Blackie’s acquaintance.” He smiles, revealing a scant handful of teeth.

“How do you do,” I say.

“Grady, git that jug back, will ya?” says Camel.

Grady trains his gaze on me, and I meet it. After a while he gets up and moves silently toward Blackie.

Camel struggles to his feet, so stiff that at one point I reach out and steady his elbow. Once he’s upright he holds the kerosene lamp out and squints into my face. He peers at my clothes, surveying me from top to bottom.

“Now what did I tell you, Blackie?” he calls out crossly. “This here ain’t no bum. Blackie, git on over here and take a look. Learn yourself the difference.”

Blackie grunts, takes one last swallow, and relinquishes the jug to Grady.

Camel squints up at me. “What did you say your name was?”

“Jacob Jankowski.”

“You got red hair.”

“So I’ve heard.”

“Where you from?”

I pause. Am I from Norwich or Ithaca? Is where you’re from the place you’re leaving or where you have roots?

“Nowhere,” I say.

Camel’s face hardens. He weaves slightly on bowed legs, casting an uneven light from the swinging lantern. “You done something, boy? You on the lam?”

“No,” I say. “Nothing like that.”

He squints at me a while longer and then nods. “All right then. None of my business no-how. Where you headed?”

“Not sure.”

“You outta work?”

“Yes sir. I reckon I am.”

“Ain’t no shame in it,” he says. “What can you do?”

“About anything,” I say.

Grady appears with the jug and hands it to Camel. He wipes its neck with his sleeve and passes it to me. “Here, have a belt.”

Now, I’m no virgin to liquor, but moonshine is another beast entirely. It burns hellfire through my chest and head. I catch my breath and fight back tears, staring Camel straight in the eyes even as my lungs threaten to combust.

Camel observes and nods slowly. “We land in Utica in the morning. I’ll take you to see Uncle Al.”

“Who? What?”

“You know. Alan Bunkel, Ringmaster Extraordinaire. Lord and Master of the Known and Unknown Universes.”

I must look baffled, because Camel lets loose with a toothless cackle. “Kid, don’t tell me you didn’t notice.”

“Notice what?” I ask.

“Shit, boys,” he hoots, looking around at the others. “He really don’t know!”

Grady and Bill smirk. Only Blackie is unamused. He scowls, pulling his hat farther down over his face.

Camel turns toward me, clears his throat, and speaks slowly, savoring each word. “You didn’t just jump a train, boy. You done jumped the Flying Squadron of the Benzini Brothers Most Spectacular Show on Earth.”

“The

what?

” I say.

Camel laughs so hard he doubles over.

“Ah, that’s precious. Precious indeed,” he says, sniffing and wiping his eyes with the back of his hand. “Ah, me. You done landed yer ass on a circus, boy.”

I blink at him.

“That there’s the big top,” he says, lifting the kerosene lamp and waving a crooked finger at the great rolls of canvas. “One of the canvas wagons caught the runs wrong and busted up real good, so here it is. Might as well find a place to sleep. It’s gonna be a few hours before we land. Just don’t lie too close to the door, that’s all. Sometimes we take them corners awful sharp.”

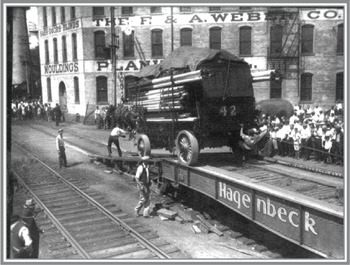

COURTESY OF THE PFENING ARCHIVES, COLUMBUS, OHIO

Three

I awake to the prolonged screeching of brakes. I’m wedged a good deal farther between the rolls of canvas than I was when I fell asleep, and I’m disoriented. It takes me a second to figure out where I am.

The train shudders to a stop and exhales. Blackie, Bill, and Grady roll to their feet and drop wordlessly out the door. After they’re gone, Camel hobbles over. He leans down and pokes me.

“Come on, kid,” he says. “You gotta get out of here before the canvas men arrive. I’m gonna try to set you up with Crazy Joe this morning.”

“Crazy Joe?” I say, sitting up. My shins are itchy and my neck hurts like a son of a bitch.

“Head horse honcho,” says Camel. “Of baggage stock, that is. August don’t let him nowhere near the ring stock. Actually, it’s probably Marlena that don’t let him near, but it don’t make no difference. She won’t let you nowhere near, neither. With Crazy Joe at least you got a shot. We had a run of bad weather and muddy lots, and a bunch of his men got tired of working Chinese and moped off. Left him a bit short.”

“Why’s he called Crazy Joe?”

“Don’t rightly know,” says Camel. He digs inside his ear and inspects his findings. “Think he was in the Big House for a while but I don’t know why. Wouldn’t suggest you ask, neither.” He wipes his finger on his pants and ambles to the doorway.

“Well, come on then!” he says, looking back at me. “We don’t got all day!” He eases himself onto the edge and slides carefully to the gravel.

I give my shins one last desperate scratch, tie my shoes, and follow.

We are adjacent to a huge grassy lot. Beyond it are scattered brick buildings, backlit by the predawn glow. Hundreds of dirty, unshaven men pour from the train and surround it, like ants on candy, cursing and stretching and lighting cigarettes. Ramps and chutes clatter to the ground, and six- and eight-horse hitches materialize from nowhere, spread out on the dirt. Horse after horse appears, heavy bob-tailed Percherons that clomp down the ramps, snorting and blowing and already in harness. Men on either side hold the swinging doors close to the sides of the ramps, keeping the animals from getting too close to the edge.

A group of men marches toward us, heads down.

“Mornin’, Camel,” says the leader as he passes us and climbs into the car. The others clamber up behind him. They surround a bundle of canvas and heave it toward the entrance, grunting with effort. It moves about a foot and a half and lands in a cloud of dust.