Warrior Pose (14 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

NBC's Miami Bureau sits on the outskirts of Miami in a non-descript, two-story, white building with dark, reflective windows to mitigate the scorching Florida heat. The minute I step inside, I feel the legacy of the great correspondents who came before me. The bureau came of age in the 1970s during the revolutions in El Salvador and Nicaragua, and the region remains important to NBC News. There are solid stories for me to cover in Miami, but most of my assignments are where I really want to beâdown in Nicaragua, Colombia, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

As I travel Latin America, I finally understand why countries here are called banana republics. In the late 1800s, bananas were unknown in North America. Then an ambitious railroad builder from Brooklyn married the daughter of the president of Costa Rica and launched an empire. As he built new railroads, he planted bananas alongside the tracks. Soon, he established numerous plantations and created what became the largest company in the world at that time: United Fruit, with farms, factories, and plantations throughout Latin America.

United Fruit acted like a colonial overlordâcontrolling commerce, transportation, communications, and the political processes of countries throughout the region. It bought the unconditional support of right-wing dictators who maintained their power by terrorizing their citizens and arresting those who defied their regimes. Workers in the fields were driven off their family farms, paid survival wages, and exposed to working conditions teeming with toxic chemicals and disease. Attempts to unionize and improve conditions were met with brutal force. Peasant uprisings were viciously suppressed. Thousands were tortured or killed. The U.S. State Department consistently supported United Fruit, and the company enjoyed close ties with the CIA, even working with them to overthrow popular leaders and replace them with easily manipulated puppet regimes. The locals in every country nicknamed United Fruit

El Pulpo

, the octopus.

I discovered the dark side of United Fruit years earlier while I was an investigative reporter at KCRA-TV in Sacramento. I had

uncovered a Nazi war criminal living in a retirement home less than ten miles from our TV station. Otto Von Bolschwing was an SS intelligence officer for the masterminds of the Holocaust. After the war, he was given safe haven in the United States, where he worked for the CIA. United Fruit, I ultimately learned, provided his cover job and false identity. As I would discover during my investigations, Von Bolschwing was one of hundreds of Nazi war criminals in the secret program.

The CIA and United Fruit were behind the right-wing military during a bloody, twelve-year civil war in El Salvador that ended in a stalemate, with some negotiated reforms but mostly business as usual. In Nicaragua, however, workers' advocate Daniel Ortega and his Sandinista Liberation Front managed to galvanize the poor people and, in 1979, overthrew longtime dictator Anastasio Somoza. In subsequent elections, Ortega became leader of the country.

Now in 1990, Ortega is facing the first serious challenge to his presidency. He's up for reelection against a former colleague named Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, who is being backed by the United States as well as conservative Nicaraguan and foreign business interests who are hoping to re-establish dominance and recover valuable businesses and estates the Sandinistas seized and turned over to workers after the revolution.

“The United States speaks a great deal about liberty and freedom, but it suppresses poor people around the world so that its corporations can make great profits,” Ortega says, making his case to our cameras in the living room at his modest home in Managua, Nicaragua. It's in a quiet neighborhood on the outskirts of the city amid rolling green hills dotted with banana trees. Ortega is sipping a

mojito

, a cocktail that originated in Cuba. Not wanting to be rude to President Ortega, of course, I sip one myself. It's a sweet blend of sugar cane juice, lime, sparkling water, crushed mint, and white rum. It was Ernest Hemingway's favorite drink, and I recall having one too many at his favorite haunt,

La Bodeguita del Medio

, a historic restaurant and bar in Havana, Cuba.

“We have brought justice and dignity to our country,” Ortega continues. “Why does your country seek to turn back the clock?”

The Berlin Wall has just fallen, but the Cold War continues. Ortega has close ties with Cuba, embraces socialism, and is vilified by the American government as a threat to the entire region. It's the “domino theory,” holding that if one country goes socialist, they all will, posing a dire threat to the United States and democracies throughout the world. The Cold War advocates never mention, however, that the real threat of a workers' revolution is to companies like United Fruit and the billions in profits they make exploiting third-world labor and resources.

“Maybe your movement swung the pendulum too far the other way,” I say to Ortega as our cameras roll. “There have been abuses and injustices committed by both sides, no?”

“Yes, and we have reined those in. We have punished the perpetrators. Still, this does not compare to more than a century of violence, exploitation, and suffering that your country has supported.”

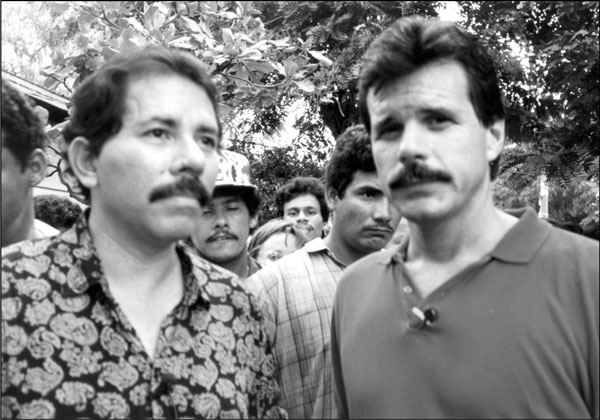

With Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, Managua, 1990.

When I sit down with Violeta Chamorro, she counters Ortega's argument. “The economy is in shambles. The poorly educated workers cannot run the factories and farms they have been given. The original owners do not deserve to lose their holdings. There must be an accommodation.”

“Some say you are too beholden to the United States,” I respond. “That you will turn your country back into little more than a banana republic.”

“This is not true.” She is firm. Dignified. “I fought against that, and now I am struggling for a better future for all our people.”

I can understand where President Ortega and challenger Chamorro are coming from. Their conflicting views are both valid. In the real world, it's never good guys versus bad guys. It's always shades of gray. Ulterior motives. Power struggles. Best and worst intentions. Often at the very same time.

Some accuse the media of liberal bias, but I hear a full array of viewpoints and perspectives at NBC and from colleagues in the field. Sure, there are raging liberals and ardent conservatives, but most are moderates. I'm not interested in taking sides and have never voted a party line. I've met few politicians I really trust and none whose rhetoric I take at face value. Our job as journalists is to do our best to find the truth and report it, avoiding outside influences and opinions. I don't feel Ortega is more correct than Chamorro, or vice versa. As long as I get on the air with a story, I couldn't care less who wins.

I stay in Nicaragua through the election as Chamorro pulls off an upset victory. There are festivals and protests simultaneously in the streets, live shots to do for

Nightly News

, packaged reports to produce for the

Today Show

. By the end of it, my back is on fire again from all the travel and constant standing. I'm popping meds like they're

chicharrónes

, the deep fried pork rind snacks so popular in

Latin America. My evening glass of wine has become two. Sometimes three. At least I'm in good company. We're all fairly accomplished drinkers, those of us addicted to exotic settings and occasional war zones.

Back at the Miami Bureau, I'm in survival mode again, carefully hiding the truth about my back from everyone. Some social events are obligatory, but after a few minutes of standing and making casual conversation I start to grit my teeth, look for the nearest exit, and seize my first opportunity to slip out unnoticed. Chronic pain makes me this way: on edge, nervous about the next flare-up, worried that at any moment my life will come crashing down all around me. Every time it flares up I feel a mixture of anger and fear coursing through my veins like hot sauce, which only makes me tenser and exacerbates the pain. Sometimes I want to scream. Other times I want to cry. But I stuff it all inside and just keep shoving myself forward, always diving into the next story.

As the spring of 1990 unfolds, money is tight at NBC, and the network's interest in Latin America is waning. There's talk of consolidation and bureau closures. Miami is rumored to be high on the list. My colleagues exchange worried glances, have hushed conversations, and secretly send out resumes. I can't even process the idea that I could be laid off after being here less than a year. I can't imagine any other life. I don't even believe one exists for me.

Then, on August 2, 1990, President Saddam Hussein of Iraq invades Kuwait.