War: What is it good for? (26 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

In theory, the country was run by emperors who traced their ancestry back to gods, but shogunsâusually hard, self-made men who had risen through the army's ranksâactually called the shots. It was a messy arrangement, but it worked surprisingly well. After conquering almost all of what we now call Japan, the shoguns oversaw investments in agriculture. Productivity and population boomed, and in 1274 and 1281, Japan even beat off Mongol invasions.

The shoguns then learned, like so many rulers in the lucky latitudes, how easily productive war could turn counterproductive when nomads were involved. To mobilize the resources needed to stop the Mongols, the shoguns had to cut so many deals with samurai and local lords that these overmighty subjects lost all reason to fear Leviathan. Across the next three hundred years, Japan slithered into its own version of feudal anarchy. By the sixteenth century (the period that Akira Kurosawa's famous film

The Seven Samurai

is set in), villages, city neighborhoods, and Buddhist temples were all hiring their own samurai. Warlords filled the countryside with castles, and violence spiked up well past anything Cadfael was used to.

Not until the 1580s did the pendulum swing back. In the years that Kiha was subduing Maui and âUmi was uniting Hawaii, a Japanese warlord named Oda Nobunaga stormed his rivals' castles and deposed the shogun. His successor, Hideyoshi, went further still, pushing through

one of the most amazing disarmaments in history. Announcing that he wanted to “benefit the people not only in this life but in the life hereafter,” he bullied his subjects into handing over their weapons so he could melt them down to make nails and bolts for a Buddha statue twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty. Government troops went on “sword hunts” to make sure that everyone shared in Hideyoshi's benefits.

Hideyoshi was not being entirely forthright, however. After disarming the people, he ramped up productive war by invading Korea, intending to swallow it and China into a single great East Asian Empire. The casualties were enormous, and when Hideyoshi died in 1598, his plan collapsed and his generals fought a civil war. Even so, his pacification of the homeland stuck. The government even demolished most of Japan's castles: in Bizen Province, for instance, the two hundred forts that had been built by 1500 had dwindled to one by 1615. For the next quarter millennium Japan was one of the least violent lands on earth. Even books describing weapons were banned.

By

A.D.

1500, migration and assimilation had pushed farming, caging, productive war, and Leviathans far beyond their original homeland in the lucky latitudes, but in some places a third force intervened: independent invention. Several parts of the world outside the lucky latitudes had at least a few potentially domesticable plants and animals, and foragers in these regions eventually had their own agricultural revolutions and revolutions in military affairs. Despite a time lag thousands of years long, they began moving down the same path that people in the lucky latitudes had already trodden.

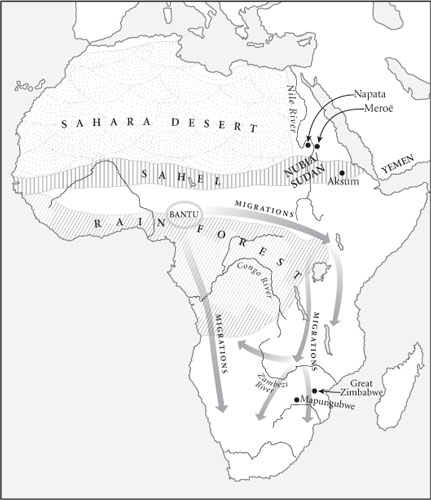

Africa is a striking case in point. Migration and assimilation certainly played big parts in bringing agriculture to the continent: Africa's first farmers were settlers from the Hilly Flanks who carried wheat, barley, and goats to the Nile Valley around 5500

B.C.

(

Figure 3.10

). As Egyptian farmers spread into what we now call Sudan, Nubian foragers emulated them, turning to agriculture of their own accord. Eventually, when Egyptian armies pressed southward after 2000

B.C.

, the Nubians discovered productive war and formed their own kingdoms. In the seventh century

B.C.

a Nubian kingâTaharqa of Napataâeven conquered Egypt.

Figure 3.10. The not-so-dark continent: sites in Africa mentioned in this chapter

Productive war was just as messy on this frontier as anywhere else, regularly turning counterproductive and bringing on collapse, only to reverse itself and create a still stronger Leviathan. By 300

B.C.

, Napata was in decline, and a great new city was flourishing at Meroë. By

A.D.

50, Meroë too was past its glory days, and the rulers of an even greater city at Aksum

were raising stone pillars a hundred feet high and sending armies across the Red Sea into what is now Yemen.

Given time, migration and assimilation might have carried caging and productive war all the way down Africa's east coast, but homegrown caging overtook them. By 3000

B.C.

, people in the Sahel, the dusty grasslands that run across Africa between the southern edge of the Sahara Desert and the northern edge of the rain forest, had domesticated sorghum, yams, and the oil palm. What happened next is controversial: some archaeologists argue that eastern and southern Africans also began inventing agriculture

independently, but most think that after 1000

B.C.

Bantu-speaking farmers from western and central Africa migrated east and south, taking ranching, farming, and caging with them and fighting with iron weapons as they went. (Whether the Bantu learned ironworking from the Mediterranean world or invented it for themselves is yet another source of controversy.)

Whatever the details, though, by Cadfael's day productive war was bringing forth Leviathans everywhere from the mouth of the Congo River to the banks of the Zambezi, setting off local revolutions in military affairs. In the thirteenth century, for instance, archaeologists have detected new styles of fighting in the Congo Basin, involving larger forces, stronger command and control, big war canoes, and new iron stabbing spears for hand-to-hand combat.

Once again, the path toward larger, safer societies was bumpy and bloody. In southeast Africa, for example, population boomed, and a kingdom called Mapungubwe emerged in the twelfth century. By 1250, it had fallen, replaced by the new city of Great Zimbabwe. By 1400, Great Zimbabwe had subdued the Shona-speaking tribes around it and the city had grown to fifteen thousand residents, protected by walls and towers so impressive that the first Europeans to see their ruins could not believe that Africans had built them.

Fifteenth-century Hawaii, Japan, and Africa (and every point in between) were all different, of course, and each had its own unique combination of migration, assimilation, and independent invention. But when we step back from the details to look at the big picture, we see much the same pattern almost everywhere. Leviathan was taking over the planet. Whenever the evidence allows us to see the details, war was producing bigger governments that drove down rates of violent death and increased prosperity. Having started down the path of caging and productive war thousands of years later than the lucky latitudes, most of the rest of the world still lagged far behind the Leviathans in Eurasia's core in

A.D.

1400, but thanks to the cycle of productive and counterproductive wars that had grown up along the edge of the steppes since

A.D.

200, the gap was narrowing.

Natural Experiments

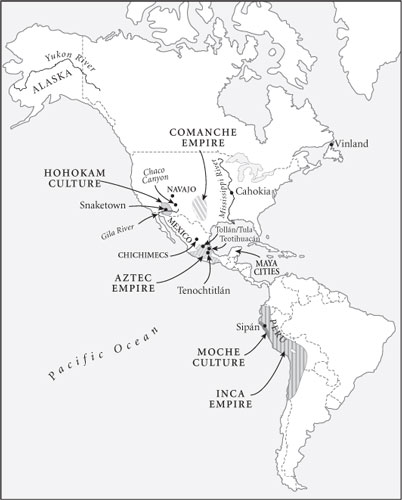

I have saved until last the most interesting case of all, America (

Figure 3.11

). Unlike Japan, the Pacific islands, and Africa, all of which were heavily impacted by emigration from Eurasia's lucky latitudes, America

largely lost contact with the Old World after its initial colonization from Siberia some fifteen thousand years ago. A few daredevils did breach the barriers, such as the Vikings who settled Vinland around

A.D.

1000 and the Polynesians who reached the West Coast soon after, but with just one exception, to which I will return in a moment, none of them had much impact. As a result, we can think of the New and Old Worlds as two independent natural experiments. Comparing their histories gives us a real

test of the theory that productive war and Leviathan are universal human responses to caging, rather than the legacies of a distinctive Western (or even Eurasian) way of war.

Figure 3.11. Sites in the Americas mentioned in this chapter

When the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés showed up in Mexico in 1519, some six thousand years had passed since Mesoamericans had invented farming. If we count six thousand years from the establishment of farming in Eurasia's Hilly Flanks around 7500

B.C.

, we get to 1500

B.C.

, by which time Egypt's pharaohs were fielding thousands of chariots carrying bronze-clad archers firing composite bows. But the Aztecs defending Tenochtitlán against Cortés had no chariots or bronze. They fought on foot, wearing padded cotton suits and wooden helmets. Their bows were crude, and their most frightening weapons were oak sticks studded with flakes of a sharp volcanic glass called obsidian. Clearly, military affairs had unfolded on different schedules in the New World and the Oldâwhich looks bad for this book's argument that productive war is a universal human response to caging.

Some of these differences are easy to explain, though. The Aztecs did not invent chariots because they could not: wild horses had gone extinct in the Americas around 12,000

B.C.

(suspiciously soon after humans arrived), and with no horses to pull them, there could be no chariots. But what of bronze spearheads and armor? In the Old World, these appeared alongside the first cities and governments (around 3500

B.C.

in Mesopotamia, 3000

B.C.

in Egypt, 2500

B.C.

in the Indus Valley, and 1900

B.C.

in China); in the New World, they did not. The oldest known American experiments with metal date from around 1000

B.C.

, and by the time of the first Leviathans a millennium later, Moche metalworkers could produce objects like the beautiful gold ornaments buried with the so-called Lords of Sipán. But at no point did Native Americans think of alloying copper with other metals to make bronze weaponsâor, if some enterprising smith did come up with the concept, it didn't catch on.

The American experience with bows and arrows is even odder. I mentioned in

Chapter 2

that arrowheads go back more than sixty thousand years in Africa. But the people who crossed the land bridge from Siberia into America fifteen thousand years ago did not bring the bow with them, and no one in America reinvented it. The first arrowheads in America, found on the banks of the Yukon River in Alaska, date from around 2300

B.C.

They were made in a style that archaeologists call the Arctic Small Tool Tradition, imported by a new wave of immigrants from Siberia. Archery

then spread excruciatingly slowly across North America, taking thirty-five hundred years to reach Mexico. When Cortés arrived, Mesoamericans had only been using bows for about four centuries, and the Aztecs' simple self bows would have looked laughably old-fashioned to Egyptian pharaohs.

This sounds like an open-and-shut case that cultural differences determined everything, provingâdepending, I suppose, on your politicsâeither that Eurasians were more rational (and therefore, perhaps, better) than Native Americans or that they were more violent (and therefore, perhaps, worse). But arguments like these have their problems too. Mesoamericans developed the problem-solving skills needed to produce remarkable calendars, raised-field farming, and irrigation. Calling these people irrationalâor just less rational than Europeansâis not very convincing.

Neither is suggesting that Native American cultures were less violent than Europeans. For many years, archaeologists treated the ancient Maya as poster children for peace, arguing that because we had found few fortifications around their cities, they must have settled their disputes nonviolently. That theory collapsed almost the minute the Mayan script was deciphered. Its main topic was war. Mayan kings fought just as much as European ones.

Some historians point instead to what the Aztecs called Flower Wars, campaigns designed to minimize casualties on both sides. These, they argue, show that Native Americans looked at fighting as a kind of performance, in contrast to the European focus on decisive battle. But this is a misunderstanding: Flower Wars were more like limited wars than ritual wars. A Flower War was a cheap way to show enemies that resistance was futile. “If that failed,” says Ross Hassig, the leading expert on Aztec warfare, “the flower war was escalated ⦠shifting from demonstrations of prowess to wars of attrition.” Aztecs, like Europeans, tried to win wars on the cheap, but when that did not work, they did whatever it took.