War: What is it good for? (18 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Once the process began, there was no turning back. The rise of Assyria spawned dozens of new small states around its edges as peripheral peoples organized governments to fight back, raising taxes and training armies. When a coalition of these enemies overthrew the Assyrians in 612

B.C.

, a sixty-year tussle over the empire's carcass ended in the rise of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the biggest the world had yet seen (although it has to be said that much of the area the Achaemenids ruled had almost no one in it, and its population was barely half what the Roman and Han Empires would one day have).

Persia's growth set off another phase of state formation around its periphery, and in the 330s

B.C.

it met the same fate as Assyria. It took just four years for Alexander the Great, ruler of what struck the Persians as a backward kingdom on their northwest frontier, to overthrow the great empire.

By then, though, still newer fringe societies were appearing, and in the third century

B.C.

Rome and Carthage fought the largest, fiercest wars in ancient history. By the time Carthage surrendered in 202

B.C.

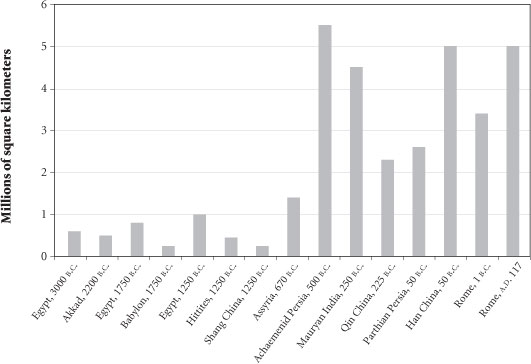

, Rome had built the greatest war machine in the world and across the next century swallowed up the entire Mediterranean Basin. For the next thousand years, the Fertile Crescent and the Mediterranean were always to be dominated by a few huge empires, holding sway overâand imposing peace onâtens of millions of people (

Figure 2.8

).

Figure 2.8. Size matters: Eurasian empires compared, 3000

B.C.âA.D.

117

This was the age, according to Hanson and Keegan, when the Western way of war was born. But when we look across the rest of Eurasia's lucky latitudes in the first millennium

B.C.

, we see remarkably similar patterns. Thanks to their later start on farming and caging after the end of the Ice Age, China and India began down this path several centuries after the Mediterranean world, but each independently discovered the same secret of success as Assyria, Greece, and Rome, raising mass armies paid for by powerful governments and winning wars in huge, face-to-face battles settled by shock tactics. Each region added its own twists to the tale, but from the Atlantic to the Pacific the story remains recognizably the same.

Once again, this is clearest in China. After being adopted later than in the Fertile Crescent, chariots continued to dominate battlefields until the

sixth century

B.C.

(the biggest Chinese chariot battle on record, at Chengpu, was in 632

B.C.

), but by 500

B.C.

kings were starting to figure out the same strategy that had worked so well for Tiglath-Pileser. They cut aristocrats out of war, granted peasants rights to their land, and then taxed and conscripted them as payback.

By the time that big horses from the steppes reached China around 400

B.C.

, battlefields were already dominated by masses of infantry with iron swords and spears, plusâancient China's great contribution to military technologyâcrossbows. A crossbow took longer to load than a composite bow and could not shoot as far, but it was simpler to use and fired iron bolts that could penetrate thicker armor, making it ideal for huge armies slugging it out at close range.

Iron reached China around 800

B.C.

, and by the fifth century smiths could make true steel, harder than anything in the Fertile Crescent. These iron weapons spread slowly, not replacing bronze completely until after 250

B.C.

, but by then there were strong similarities between ways of fighting at the two ends of Eurasia.

As in the Fertile Crescent and the Mediterranean, Leviathan kept outrunning the Red Queen, with small feuding states being combined into large pacified ones. Chinese texts tell us there were 148 separate states in the Yellow River valley in 771

B.C.

These fought constantly, and by 450

B.C.

just fourteen remained, but only four of them really counted. As they struggled, new states sprang up to their south and west, but in the third century

B.C.

, one of the western statesâQinâdevoured all the rest.

In western Eurasia, the climax of violence began when Rome and Carthage went to war in the 260s

B.C.

, and eastern Eurasia followed much the same timetable. The Changping campaign of 262â260 was probably the biggest single operation in ancient times, with at least half a million men from Qin and Zhao locked in trench warfare. By day, the armies tunneled under enemy lines; by night, they infiltrated raiding parties and stormed strongpoints.

The tide finally turned when Qin spies convinced the king of Zhao that his general was too old and cautious to prosecute the war properly. Zhao sent a younger, wilder man in his place. According to our main sourceâthe historian Sima Qianâthe new general was such a poor choice that even his parents complained, and just as Qin had hoped, he promptly led a frontal assault. Thirty thousand Qin cavalry then sprang a trap, enveloping the Zhao army on both flanks. Rather like the archaeologists who call Sanyangzhuang “the Chinese Pompeii,” military historians often call the

Battle of Changping “the Chinese Cannae,” likening it to Hannibal's equally dramatic double envelopment of a Roman army in 216

B.C.

Cut off, the Zhao troops dug in on a hill and waited for relief, but none came. After forty-six days, with their rash young general dead and their food and water gone, they surrendered. Another bad move: Qin massacred the entire force, except for the youngest 240 men, who were left alive to spread word of the disaster.

Qin had invented the body count, looking to win wars not by subtlety or maneuver but by simply killing so many people that resistance became impossible. We will never know the total numbers beheaded, dismembered, and buried alive, but it must have been several million, and over the next forty years Qin bled its rival warring states white.

When Qin's King Zheng accepted the surrender of his last enemy in 221

B.C.

, he renamed himself Shihuangdi, “August First Emperor.” Most famous today for the eight-thousand-man Terra-Cotta Army that accompanied him into death, the First Emperor seems to have been hell-bent on proving Calgacus right about wastelands. Rather than demobilizing his armies and leaving his subjects to enjoy the fruits of peace, he dragooned them into vast construction projects, where hundreds of thousands died laboring on his roads, canals, and Great Wall. Like Rome, Qin replaced war with law, but unlike Rome, Qin managed to make law even worse than war. “At the end of ten years,” the historian Sima Qian claimed, “the people were content, the hills were free of brigands, men fought resolutely in war, and villages and towns were well ruled,” but in reality the costs were ruinous. When the First Emperor died in 210

B.C.

, his son (named, predictably, Second Emperor) was overthrown within twelve months. After a brief but brutal civil war, the Han dynasty took over the empire and began tempering the excesses of Qin state violence. Within a century, the Han were overseeing from their bustling capital of Chang'an the Pax Sinica described earlier in this chapter.

We see a similar story line in India, although the evidence is as usual messier. Iron weapons largely replaced bronze in the fifth century

B.C.

, cavalry appeared in the fourth (although chariots hung on here for another three hundred years), and Indian kings were raising forces hundreds of thousands strong by the third. There were differences too, though. One passage of the

Arthashastra

(the great book of statecraft mentioned earlier in this chapter) rated infantry in chain mail as the best troops for battling full armies, but most Indian foot soldiers were unarmored bowmen, not

the heavy spear- and swordsmen of Assyria, Greece, Rome, and China. The best-trained Indian infantry (the

maula,

a hereditary standing army) could be as disciplined and determined as anyone, but the grunts were always at the bottom of the fourfold hierarchy of Indian troops. This, however, might have been because what the Indians had in the top rank was bigger and arguably better than any kind of infantry: the elephant.

11

“A king relies mainly on elephants for victory,” the

Arthashastra

bluntly tells us. What it does not tell us, though, is how unreliable elephants could be. Even after years of training they remained panicky, regularly stampeding in the thick of battle. If an elephant rampaged in the wrong direction, the only way to stop it from trampling friends rather than foes was for its driver to hammer a wooden wedge into the base of its skull. The result was that even the winning side often lost most of its expensively trained elephants. But despite all these drawbacks, when elephants got moving in the right direction, few armies would stand firm. “Elephants,” the

Arthashastra

calmly explains, “shall be used to: destroy the four constituents of the enemy's forces whether combined or separate; trampling the center, flanks, or wings.”

An elephant charge might have been the most terrifying experience in ancient war. Each beast weighed in at three to five tons, and many carried a ton or more of armor. Hundreds or even thousands would come crashing across the plain, shaking the earth in deafening rage. The defenders would try to slash their hamstrings, castrate them with spears, and blind them with arrows; the attackers would fling down javelins, thrust with pikes, and goad their mounts to trample men underfoot, exploding their bones and organs. Horsesâsensible animalsâwould not go near elephants.

Even Alexander the Great had to concede that armored elephants were formidable shock troops. After overthrowing the whole Persian Empire in just eight years, he reached the Hydaspes River in modern Pakistan in 326

B.C.

, only to find King Puru (called Porus in the Greek sources) blocking his path. Puru's hundreds of chariots proved useless against the Macedonian phalanx, but his elephants were another story altogether. To get the better of them, Alexander had to pull off the most brilliantly executed maneuver of his whole career, but on learning that Puru was actually just a second-tier king, and that the Nandas (precursors of the Mauryans) who ruled the Ganges Valley had far more elephants, Alexander decided to turn back.

In 305

B.C.

, after Alexander's death, his former general Seleucus returned to the Indus River and squared off against Chandragupta (rendered in Greek as Sandrakottos), founder of the Mauryan dynasty, somewhere along its banks. This time the Macedonians could not prevail. Even more impressed by elephants than Alexander, Seleucus agreed to give Chandragupta the rich provinces of what are now Pakistan and eastern Iran in exchange for five hundred of the beasts. This sounds like a bad deal for Seleucus, but his judgment was vindicated. Four years later, after his men had herded the pachyderms twenty-five hundred miles to the shores of the Mediterranean, the beasts tipped the scale in the Battle of Ipsus, securing his kingdom in southwest Asia. These new shock weapons so impressed the monarchs of the Mediterranean that in the third century

B.C.

, everyone who was anyone bought, begged, or borrowed his own set of elephants. The Carthaginian general Hannibal even dragged dozens of them over the Alps in 218

B.C.

The wars being fought in South Asia in these years proved just as productive as those of East Asia and western Eurasia. Dozens of small states formed in the Ganges Plain during the sixth century

B.C.

, fighting constantly, and by 500

B.C.

four big statesâMagadha, Kosala, Kashi, and the Vrijji clansâhad swallowed all the rest. India's great epic poem the

Mahabharata

even came up with a name for this process: “the law of the fishes.” In times of drought, the poet says, the big fish eat the little ones.

As the Ganges states expanded, new small states formed around their edges in the Indus Valley and the Deccan. By 450

B.C.

, though, just one big fish (Magadha) survived in the Ganges, and from its great walled capital at Pataliputra three successive dynasties pushed their power deeper into India before the Mauryans outdid them all. Raising armies of hundreds of elephants, thousands of cavalry, and tens of thousands of infantry, they fought massive set-piece battles and undertook complex sieges.

The Mauryans' wars climaxed around 260

B.C.

, the same time as Rome's and Qin's, with the great victory of King Ashoka over Kalinga that I mentioned earlier in this chapter. “A hundred and fifty thousand people were deported, a hundred thousand were killed, and many times that number [also] perished,” Ashoka recordedâonly for victor's remorse to set in and the reign of

dhamma

to begin.

When we look at the big picture in the first millennium

B.C.

, it is hard to find much sign of a unique Western way of war, with its distinction between Europeans closing to arm's length and Asians keeping their distance.

From China to the Mediterranean, the first millennium

B.C.

saw the rise of much bigger Leviathans that taxed and controlled their swelling populations more directly than ever before. Their rulers were killers, ready to do whatever it took to stay on top. They conscripted hundreds of thousands of men, disciplined them fiercely, and sent them in search of decisive victories, which were won with bloody, face-to-face shock attacks. In Assyria, Greece, Rome, and China, the decisive blow usually came from heavy infantry. In Persia and Macedon, cavalry played a bigger part. In India, it was down to elephants. But from one end of the lucky latitudes to the other, the same basic story played out across the first millennium

B.C.