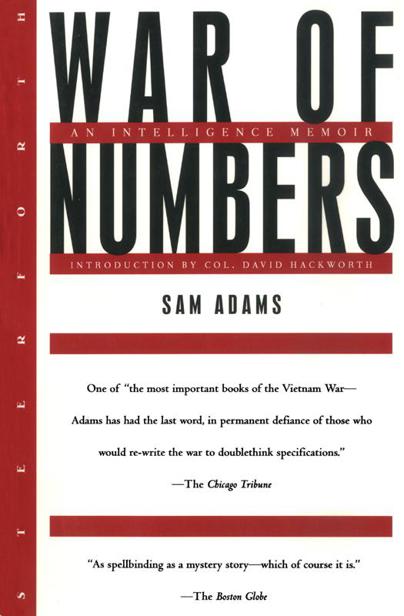

War of Numbers

Authors: Sam Adams

Copyright © 1994 by Anne Adams

Introduction Copyright © 1994 by David Hackworth

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections

from this book, write to: Steerforth Press L.C., P.O. Box 70,

South Royalton, Vermont 05068.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58642-202-8

1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961–1975—Secret service—United States.

2. Adams, Sam, 1933–1988. 3. United States. Central Intelligence Agency—Officials and employees—Biography.

I. Title.

DS559.M44A33 1994

959.704′38—dc20 93–50207

v3.1

To Colonel Gains B. Hawkins

and to my sons, Clayton and Abraham

“My dear Spencer, I should define tragedy as a theory killed by a fact.”

—Huxley

CONTENTS

3

THE PUZZLE OF VIETCONG MORALE

INTRODUCTION

WALTER CRONKITE SUMMED up the national mood in the third year of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War when he said during the 1968 Vietnamese Tet Offensive, “What the hell is going on? I thought we were winning the war.”

Thousands of books have been written about the Vietnam War. Yet this unfinished memoir by Sam Adams could well be the most important of them and the most damning indictment of the “best and brightest” who engineered the war, from the White House policy makers to those top military and intelligence brass who lied about the war from womb to tomb.

War of Numbers

gives the inside story, chapter and verse, outlining why America’s intelligence community is as sick as a junkyard dog that’s gotten into the rat poison.

Had the truth about the enemy’s strength and intentions been revealed before the Vietnamese New Year in 1968, 2,200 American lives might have been saved and tens of thousands of other American casualties could well have been prevented. A flawed and manipulated intelligence system cut these brave men down almost with the precision of machine gun fire. How many names are on the Black Wall of the Vietnam memorial in Washington today because of a corrupted intelligence machine? When commanders expecting 100 men to attack were hit by a thousand instead, it was the grunt who paid the grim price for fraudulent bookkeeping.

War of Numbers

is about one man’s effort to get the truth to the grunts and their sergeants, captains, and colonels who fought the war down in the blood and mud and who needed to know the straight skinny about their Vietnamese enemy.

The man who made this effort was Samuel Adams, a young Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) analyst who could not be bought or shut up by threat of ruining his career, but hung on like a pit bull to his gut conviction that persons on high were cooking the books on enemy strength in Vietnam. Adams had the passion, moral courage, and integrity of Oliver Cromwell just after he got up from his knees from prayers, a most uncommon trait in any bureaucrat. In his friendly way Adams took on his bosses toe-to-toe, from CIA director Richard Helms on down the corrupted go-along-to-get-along chain-of-command within the CIA, the Pentagon, and the White House. He gave fits to the men appointed by President Lyndon Johnson to top jobs, and he presented the same dogged demand for honest accounting to Generals William Westmoreland and Phillip Davidson (the Theater Intelligence Officer for American forces in Vietnam) and platoons of deceptive colonels who forgot their solemn oaths to defend their country.

In

The Art of War,

written over 2,500 years ago, Sun Tzu said, “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.” Had Sam Adams been successful in getting the truth out, tens of thousands of lives would not have been shattered in Vietnam. His report would have clearly told Walter Cronkite who was winning and who was losing.

Across the U.S.A. in 1968, television images of the Vietcong’s massive and coordinated assault struck the American people with perhaps as great an impact as the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The terrible battles fought simultaneously across Vietnam in early 1968 shocked, confused, and depressed the public. They had been assured for months by President Johnson, the Ambassador to Vietnam Ellsworth Bunker, and the

American commander in the field, General Westmoreland, that we were winning the war in spades and that the Vietcong were about to go down for the count.

The Tet offensive was a stinging tactical defeat for the Vietnamese insurgents when measured by Western military standards. Yet the TV was telling a different story. The small screen clearly showed the Vietcong as a potent and skillful force, and the communists as far from being defeated. The American people realized they’d been led down the primrose path, conned by political double talk. The sight of Vietcong holed up in the U.S. Embassy in the middle of Saigon told the American people with one picture all they needed to know. That picture put a lie to Westmoreland’s pronouncement in the fall of 1967 that “whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing.”

After years of solemn assurance that the Vietcong faced imminent defeat, the American people were dismayed to discover the enemy all over the place like ants at a barbecue. How could America’s top officials not know that North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap was going to launch a complex and massive attack involving hundreds of thousands of Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers striking within a 24-hour period in virtually every major city in South Vietnam? How could our multi-billion dollar, highly sophisticated intelligence community have failed to see this attack coming?

Ironically, as the reader will see in the gripping pages that follow, just ten weeks before the Tet attack, the CIA analyst Joe Hovey had predicted from Saigon: “All-out offensive … January to March 1968 … urban centers.” Hovey’s bull’s-eye analysis had made the rounds among the CIA’s top brass and was even dispatched to the White House, where President Johnson read it 15 days before the attack. However, a note from George Carver, a top CIA official, shot down Hovey’s warning. Carver said Hovey was “crying wolf.”

Throughout the war, the intelligence and military top brass sometimes seemed incapable of getting anything right. In 1965, a CIA branch chief, Ed Hauck, said, “The Vietnam War’s going to last a long

time. In fact, the war’s going to last so long we’re going to get sick of it. We’re an impatient people, we Americans, and you wait and see what happens when our casualties go up, and stay up, for years and years. We’ll have riots in the streets, like France had in the fifties. No, we’re not going to ‘clean it up.’ The Vietnamese Communists will. Eventually, when we tire of the war, we’ll come home. Then they’ll take Saigon. I give them ten years to do it, maybe twenty.” What a heart breaker that this wasn’t said to the members of the U.S. Congress on national TV! Communist tanks rolled into Saigon ten years to the month after Hauck made his prophetic statement.

Intelligence failures are no anomaly in American history. Since the Civil War, the U.S. intelligence community has dropped the ball as often as a freshman high school football team in its first game. During World War II, our spooks didn’t see the Japanese coming in 1941 and missed the massive Nazi attack in the Ardennes in 1944. These blunders, which cost thousands of lives, were followed by the failure to identify the June 1950 North Korean invasion of South Korea, or the fact that five months later, a million man Chinese army entered the war and surreptitiously slipped behind U.S. forces deployed near the Yulu River, cutting them off. Only brave men prevented America from suffering one of its worst military defeats. Korea was followed by more intelligence failures, from the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in 1961 to Tet in 1968 to the 1979 failure to foresee the revolution that dethroned the Shah of Iran. Intelligence blunders continued in Beirut and Grenada in 1983, followed by the “let’s get Noriega” fiasco in Panama in 1989. But the biggest screw-up made by America’s inept multi-billion dollar intelligence machine over the four-decade-long Cold War was probably its failure to realize that the Soviet Union was finished well before its Iron Curtain came tumbling down like Humpty Dumpty. Even after the Berlin Wall disappeared in a night, the CIA director, the Secretary of Defense, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff wouldn’t concede that the Cold War was over. For months afterward they continued to chant, “the Russians are coming.”

It’s obvious from these examples that from 1945 to the end of the Cold War, the U.S. intelligence community has been too often out to a

very long, multi-martini lunch. Yet there has been little improvement since the cold war ended. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, the intelligence community—miracle of miracles—finally got it on the nose. They predicted the exact date, but failed to determine Iraq’s strength or its disposition of nuclear and chemical capabilities, and from Desert Shield to Desert Storm, U.S. intelligence seldom got the Iraqis’ military intentions, strength, or disposition right. Subsequent to the invasion, they reported that a half-million man Iraqi army—“the fourth largest in the world”—was deployed in and around occupied Kuwait, when in fact we now know that less than a third of that figure was on the battlefield. The intelligence community greatly inflated the Iraqi military strength, whereas in Vietnam, as this brilliant book describes, the enemy’s size was purposely deflated by almost fifty percent. In both cases, as throughout the cold war, intelligence estimates were juggled to suit political purposes.

The Desert Storm commander, General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, told Congress in 1991 that military intelligence in the Gulf War was both a triumph and a failure. In the Gulf, I believe, the failures overwhelmed the triumphs. The Republican Guards’ will to fight was overrated, as was the Iraqi Army’s combat effectiveness. Intelligence also failed to pinpoint the number of Iraqi Scud missile launchers or to estimate the effectiveness of the naval blockade and economic embargo. Satellite systems provided an unprecedented amount of information, but it was often late in reaching the user. Cloudy days made observation spotty, bomb-damage assessment was both delayed by foul weather and far from accurate. Iraqi military codes were cracked early in the game, but the shortage of skilled translators impeded the flow of radio intercepts, and lack of access to the Iraqi leadership doomed the allies to ignorance of Saddam Hussein’s true intentions. One general said he had stacks of satellite imagery, but would swap it all for “one good spy on the ground.”