Wandering Greeks (19 page)

Authors: Robert Garland

We do not know how long the evacuation took to implement, though it seems that the exercise was still going on when the Peloponnesians first invaded Attica in late May or early June 431 (2.18). Families living in the outlying demes probably had to spend at least two nights on the road, since some were located thirty miles or more from Athens. It is unclear how the flow of refugees was handled or what facilities were available either en route or on arrival. We should presumably imagine a long line queuing outside the city gates when the migration was at its heightâassuming that the evacuees knew how to queue. And once inside the city, how and where were they fed? Who took responsibility for their welfare? How were they assigned a place to bed down? Many of the refugees must have arrived footsore, exhausted, and demoralized, particularly the pregnant women, the elderly, and the infirm.

It is also unclear what percentage of country dwellers actually obeyed the summons that the

dêmos

had issued. After all, it would have been extremely difficult to enforce. Inevitably, some must have been too sick or too frail to make the journey, while others of an independent mindset may have calculated that their farms were so remote that they would be safe against depredation from the enemy. They were right. The Peloponnesians invaded Attica five times, but never ravaged Decelea, Marathon, or even the Academy just outside the city walls, destined to be the future site of Plato's philosophical school (Hansen 2005, 54).

Inevitably disaffection ran high among segments of the population once the Peloponnesians, some 30,000 in all, invaded Attica. We know this to have been the case at the outlying deme of Acharnae, whose

inhabitants were among the first to see their farms being ravaged and who constituted a sizable percentage of Athens's army. Later, exasperated, weakened, and demoralized, the citizen body as a whole took vengeance on Pericles for causing such hardship by ousting him from the board of ten generals, though it later relented and reinstated him.

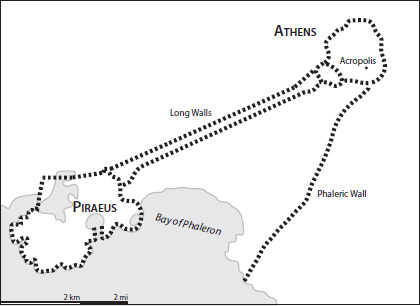

MAP 6

Athens, Piraeus, and the Long Walls.

Though a handful of wealthy families owned a second home in the city while other Athenians had relatives or friends whose homes served as a

kataphugê

(place of refuge) (2.17.1), the vast majority had to settle either where they happened upon a vacant space or else where the authorities directed themâthat is to say, in sanctuaries and hero shrines, beside the fortification walls, and on land that had previously been unoccupied (see

map 6

). Even land that lay under a curse was eventually settled, including an unidentified plot below the Acropolis called the Pelargicum. Only sanctuaries that could be locked up, notably the Acropolis and the temple of Eleusinian Demeter, remained out of bounds. At first all the refugees were crammed into Athens. As the pressure on space

increased, however, they were permitted to settle along the unoccupied strips inside the Long Walls, as well as in the Piraeus (2.17.3). It was the dense concentration of evacuees in the Piraeus that was probably responsible for the outbreak of plague, since the port was largely dependent for its drinking water on cisterns that caught rainwater, and these quickly became polluted (Thuc. 2.48.2).

Perhaps the wood that had been salvaged was used to fashion the temporary homes that Thucydides refers to as “stifling shacks” (2.52.2). Those who lacked this resource would have had to live in makeshift tents. The entire urban area now became the ancient equivalent of a modern day refugee camp, divided probably along demotic or tribal lines. Perhaps the Athenians derived some small comfort from the inspirational speech that Pericles gave in late September or early October over those who had fallen in the first year of the war (2.34â46). Conceivably the full horror of their circumstances had yet to sink in. It would do so a few months later, when the plague broke out.

Thucydides says nothing further about the evacuees, other than to note that it was they who suffered most from the plague (2.52.1). Though he describes the symptoms of the disease in painstaking detail, he says nothing of the toll it took on family life, other than to deplore the lawlessness that it engendered. It is estimated that infant mortality commonly ran at least as high as 25 percent in the ancient world. Given the many debilitating diseases that would have afflicted the refugees, it may well have doubled in this period.

The maximum number of days that the invasion lasted each year was forty (2.57.2), and after the Peloponnesians had departed, perhaps in June, the evacuees would have been free to return to their homes. Since the Peloponnesians presumably targeted a fresh area each year, as the war continued more and more Athenians would have returned to find their farms laid waste. The annual cycle was repeated until 425, when the Spartans who had been holed up on the island of Sphacteria surrendered to the Athenians. And yet this momentous event receives no mention in Thucydides. It is possible that some evacuees, out of either preference or inertia, may have chosen to remain in the city. If so, one of the most significant social consequences of the war was to cause a shift

from the countryside to the city, though the evidence for such a migration is tantalizingly inconclusive.

Several other cities had evacuated their rural populations on the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. When the Athenians invaded Boeotia, for instance, the inhabitants of several townships in Boeotia had migrated to Thebes, thereby doubling the size of its population (

Hell. Oxy.

12.3). Likewise, before the Thebans began investing Plataea, the Athenians had escorted all the women, children, and other noncombatants to Athens, where they remained for the duration of the war (Thuc. 2.6.3; see earlier,

chapter 5

). Though these are the only examples that we hear of, other communities may well have responded similarly. One of the largest evacuations must have been that of the Syracusans in 414, in advance of the Athenian attempt to invest their city by land and by sea (cf. Thuc. 6.102).

Evacuations during the Punic Wars in Sicily

A number of Greek cities in Sicily were forced to evacuate their populations during the First and Second Punic Wars that were fought between Dionysius I of Syracuse and the Carthaginians. In 406, the year of the outbreak of the first of these wars, the Carthaginians began besieging Acragas, whose people had refused their offer of an alliance. As the siege dragged on, the city began to run out of food. Eventually, when the Carthaginians intercepted a consignment of grain that the Syracusans had sent for their relief, their generals ordered an immediate evacuation (see

map 2

). So one night in mid-December the entire population departed under military escort for Gela, a coastal city that lay some 40 miles to the east. Diodorus graphically describes the scene as follows (13.89.1â3):

Because there was such a mass of men, women and children leaving the city, a sudden outburst of tears and lamentation filled people's homes. Fear of the enemy gripped them, while at the same time, because of the haste with which they had to act, they were compelled to abandon to the barbarians all

the things that had given them so much joyâ¦. It was not only the wealth of this great city that was being left behind but also a great multitude of human beings. For the sick were neglected by their relatives, since everyone looked after his own interests. Those, too, who were elderly, were abandoned because of their infirmity. Many who reckoned that separation from their homeland was equal to death laid violent hands upon themselves so that they might expire in the family home. The multitude that left the city, however, was at least under military escort as far as Gela. The highway and all the parts of the countryside leading to Gela was thronged with women, children, and young girls, who, exchanging the pampered lifestyle to which they had been accustomed for a strenuous march and extreme hardship, held out to the bitter end, their spirits toughened by fear.

The Carthaginians took control of Acragas the next day. Almost all of those who had remained in the city were massacred. Acragasâa very rich cityâwas sacked and all its treasures were shipped to Carthage.

There is no knowing how the evacuees survived the long march. Though it is inspiring to read of “spirits toughened by fear,” many surely collapsed along the way. A trek of 40 miles undertaken by night is a challenge even for the most vigorous spirits, as Diodorus concedes. He indicates that the evacuees did not walk in a column but spread themselves out over the countryside, which was inevitable given the fact that the “road” would have been little better than a dirt track, so they would also have been extremely vulnerable to predators. We learn nothing about their reception by the Geloans. How much advance warning had they received? In the event Gela proved to be only a temporary stop for the refugees, who “some time later” were permitted by the Syracusans to settle in Leontini (13.89.4).

A year later they were uprooted again. Following his defeat at the Battle of Gela, Dionysius negotiated a temporary truce with the Carthaginians to recover his dead. Under cover of darkness he then evacuated the population of Gela (including presumably the Acragantine refugees), by leaving fires that burned all night to deceive the enemy. No doubt the mood of the evacuees would have been made more miserable by the fact that they had to leave their dead unburied.

FIGURE 11

Bronze

onkia

(a coin used by the Sicilian Greeks equivalent to one-sixtieth of an Attic

drachma

) from Camarina, ca. 420â405. The obverse depicts the head of a gorgon. The reverse depicts an owl with a lizard in its left claw. The legend reads

KAM

(

ARINAIÃN

). According to tradition Camarina was founded in ca. 598 by settlers from Syracuse. It was destroyed by Gelon in 484 and its population transferred to Syracuse. It remained practically deserted until its refoundation by settlers from Gela in 461. In 405 Dionysius I forcibly evacuated the population to Syracuse, whereupon the Carthaginians destroyed the abandoned city. This coin is dated to the years shortly before that destruction. Not long afterward the refugees left Syracuse for Leontini. Camarina was repopulated by Timoleon (D.S. 16.82.7; cf. Talbert 1974, 149â50).

A few days later, as Diodorus reports, Dionysius ordered the evacuation of Camarina, a coastal city that lay 20 miles to the east of Gela, calculating that it would have been unable to withstand a siege once winter advanced (13.111.3â6):

Their fear did not permit the people of Camarina to delay. Some of them grabbed the silver and gold they possessed and anything else that they could easily transport. Others, however, fled only with their parents and infant children, paying no thought to their valuables. A number of elderly and sick people who had no friends or relatives were abandoned, since the Carthaginians were expected to arrive any minuteâ¦. Now that the inhabitants of two cities had been uprooted, the countryside was awash with women and children and every manner of riff-raff. When the troops saw this, they were incensed at Dionysius and pitied the lot of those who were his luckless victims. For they saw freeborn boys and young girls of marriageable age hurrying along the road in a manner that was quite indecent for persons

of their years. In similar fashion they felt sympathy for the elderly, as they saw them being compelled beyond their natural resources to keep up with those still in the prime of life.