Virginia Hamilton (19 page)

Authors: Dustland: The Justice Cycle (Book Two)

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #General

“Well, for …” I must have been tired! she thought. She hadn’t felt it at all. But she did recall she had been on her feet since early morning, and by evening still busy baking for the—

For a moment Mrs. Douglass couldn’t move. Her limbs felt heavy and fragile and she didn’t want to move them. If she could just stay in bed, maybe she could hold her world together. But slowly she got up off the bed. Blindly she found the door and hurried down the dark hall. Would not look at open bedroom doors, empty rooms, as she passed them. She would not.

She was out of the house and in the backyard. From the light spilling into the yard from rear windows, she saw Mr. Douglass carefully dollying Thomas’ kettledrums through the gate from the field.

He’d covered the drums with a dropcloth to keep moisture off them. He’d stood in the field an hour, listening, hoping, feeling the night slip over him.

He did not look at his wife as he went by her; he struggled with the dolly up onto the porch and into the house. He took the drums into Thomas’ and Levi’s room. He had his boy’s purple hat under his arm. Mrs. Douglass had seen it. She followed him in; when he had finished, he found her seated on the edge of the couch.

He sat himself next to her, taking her hand.

At last she spoke. “Well,” she said.

“Yes,” he said. She was controlling herself. That was good, he thought.

“When did it happen?” she asked him.

“I was on the screened porch, reading the paper,” he said. “The light was going, it got dark; I couldn’t see so well and turned on the lamp. Somehow the lamp made me realize how quiet everything was. Even with the riot of birdcalls, there was a kind of stillness. You know how the mockingbirds will sound out before they sleep.”

“Yes,” she said softly.

“I went on around the house and on out through the backyard to see what was up. And it was over.”

“Did you go down to their house?”

“Yes,” he said. “His mother was there. But Dorian had gone.”

“Yes,” she said. “To complete the unit.”

“Yes.”

They sat there, holding on.

After a time he said, “You have to keep on going, that’s all.”

“I know,” she said.

“They always do come back,” he said.

“Do you know where they go to prepare …”

“Yes,” he said, “but it does no good to know. She wouldn’t let us pass.”

“I do hate that woman, I can’t help myself.” Her voice trembled.

“I know,” he said. “But there’s no need. It comes from them, not Mrs. Jefferson. Actually, it comes from us. We brought them into this world.”

“Yes, and why don’t

we

have it?”

“Because. It’s their time, not ours.”

“You mean our human race is done?”

“Just our part of it,” he said. “Not all at once. But they are the new order.”

She shook her head in denial, yet knew it was true.

After a time she spoke again, her voice trembling now. “Know what the day after tomorrow is?” she asked.

“What?” he said.

“Justice’s birthday.”

“No! Yes, it sure is!”

“The nineteenth,” she said. “She’ll be twelve.”

“Still a baby,” he said. “Twelve.”

“Or twelve thousand and ninety-four. Or twelve million!”

“June, don’t.”

“I ordered a pretty store-bought cake, too, better than I could make it look, just for her. I invited all of the boys and girls, too.”

“You mean you already told them?”

“Yep. It was going to be the biggest and best surprise party she ever saw.”

He thought a moment. “Well, you can still do it,” he said. “They’ll be back. They never stay that long.”

“I’m so afraid.”

“Don’t, June. They’ll be back, I swear they will. They have always come back.”

She stared at him, peered into his eyes as if to discover lies, worries, tricks. It was the worst, most forlorn look he had ever seen. He kept his eyes steady. Thought gentle, easy thoughts, no fear anywhere.

“You promise me they’ll come back?” she said. “Promise me my boys? Promise me? Promise me Justice!”

His voice was steady. Power or no, he knew his kids. He smiled. “I promise you,” he said.

Virginia Hamilton (1934–2002) was the author of forty-one books for young readers and their older allies, including

M.C. Higgins, the Great

, which won the National Book Award, the Newbery Medal, and the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, three of the most prestigious awards in youth literature. Hamilton’s many successful titles earned her numerous other awards, including the international Hans Christian Andersen Award, which honors authors who have made exceptional contributions to children’s literature, the Coretta Scott King Award, and a MacArthur Fellowship, or “Genius Award.”

Virginia Esther Hamilton was born in 1934 outside the college town of Yellow Springs, Ohio. She was the youngest of five children born to Kenneth James and Etta Belle Perry Hamilton. Her grandfather on her mother’s side, a man named Levi Perry, had been brought to the area as an infant probably through the Underground Railroad shortly before the Civil War. Hamilton grew up amid a large extended family in picturesque farmlands and forests. She loved her home and would end up spending much of her adult life in the area.

Hamilton excelled as a student and graduated at the top of her high school class, winning a full scholarship to Antioch College in Yellow Springs. Hamilton transferred to Ohio State University in nearby Columbus, Ohio, in order to study literature and creative writing. In 1958, she moved to New York City in hopes of publishing her fiction. During her early years in New York, she supported herself with jobs as an accountant, a museum receptionist, and even a nightclub singer. She took additional writing courses at the New School for Social Research and continued to meet other writers, including the poet Arnold Adoff, whom she married in 1960. The couple had two children, daughter Leigh in 1963 and son Jaime in 1967. In 1969, the family moved to Yellow Springs and built a new home on the old Perry-Hamilton farm. Here, Virginia and Arnold were able to devote more time to writing books.

Hamilton’s first published novel,

Zeely

, was published in 1967.

Zeely

was an instant success, winning a Nancy Bloch Award and earning recognition as an American Library Association Notable Children’s Book. After returning to Yellow Springs with her young family, Hamilton began to write and publish a book nearly every year. Though most of her writing targeted young adults or children, she experimented in a wide range of styles and genres. Her second book,

The House of Dies Drear

(1968), is a haunting mystery that won the Edgar Allan Poe Award.

The Planet of Junior Brown

(1971) and

Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush

(1982) rely on elements of fantasy and science fiction. Many of her titles focus on the importance of family, including

M.C. Higgins, the Great

(1974) and

Cousins

(1990). Much of Hamilton’s work explores African American history, such as her fictionalized account

Anthony Burns: The Defeat and Triumph of a Fugitive Slave

(1988).

Hamilton passed away in 2002 after a long battle with breast cancer. She is survived by her husband Arnold Adoff and their two children.

For further information, please visit Hamilton’s updated and comprehensive website:

www.virginiahamilton.com

A twelve-year-old Hamilton in 1948, when she was in the seventh grade.

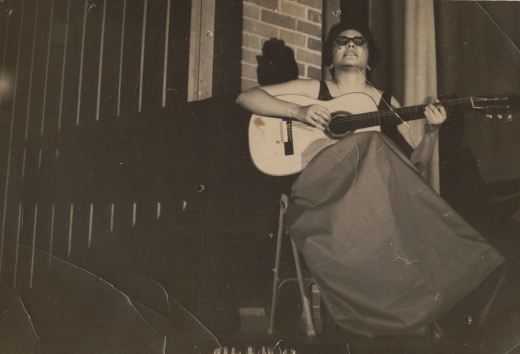

Hamilton at a New York City club while she was a student at Antioch College in the mid-1950s. She often performed as a folk and jazz vocalist in clubs and larger venues.

Hamilton with her brothers, Buster and Bill, and sisters, Barbara and Nina, around 1954.

Hamilton’s head shots. The first was taken while she was a teenager in the early 1950s. The second was taken in her New York City apartment in the late 1960s, before she and Adoff built their house in Yellow Springs.

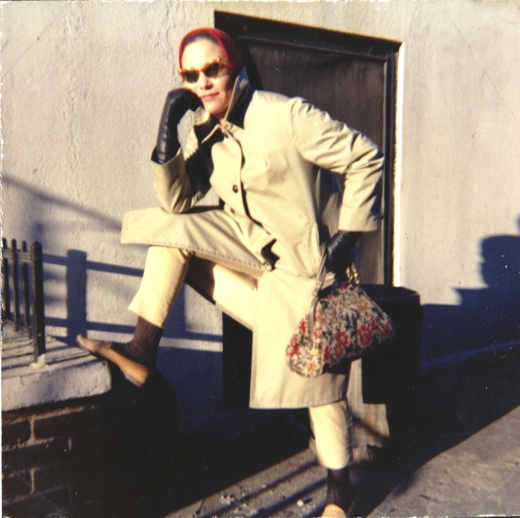

Hamilton outside of her first New York City apartment, which she shared with Adoff, around 1960. The couple moved to a below-street-level single room on Jane Street and, Adoff says, “thought we were such hot stuff, living in the Village and taking our places in that wonderful and long line of writers banging their heads against the wall . . . but in style.”