Vintage Ford (13 page)

Of course, it had occurred to him that what he might be was just a cringing, lying coward who didn't have the nerve to face a life alone; couldn't fend for himself in a complex world full of his own acts' consequences. Though that was merely a conventional way of understanding life, another soap-opera viewâabout which he knew better. He was a stayer. He was a man who didn't have to do the obvious thing. He would be there to preside over the messy consequences of life's turmoils. This was, he thought, his one innate strength of character.

Only now, oddly, he was in limbo. The “there” where he'd promised to stay seemed to have suddenly separated into pieces and receded. And it was invigorating. He felt, in fact, that although Barbara had seemed to bring it about, he may have caused all this himself, even though it was probably inevitableâdestined to happen to the two of them no matter what the cause or outcome.

He went to the bar cart in the den, poured some scotch into his milk, and came back and sat in a kitchen chair in front of the sliding glass door. Two dogs trotted across the grass in the rectangle of light that fell from the window. Shortly after, another two dogs came throughâone the springer spaniel he regularly heard yapping at night. And then a small scruffy lone dog, sniffing the ground behind the other four. This dog stopped and peered at Austin, blinked, then trotted out of the light.

Austin had been imagining Barbara checked into an expensive hotel downtown, drinking champagne, ordering a Cobb salad from room service and thinking the same things he'd been thinking. But what he was actually beginning to feel now, and grimly, was that when push came to shove, the aftermath of almost anything he'd done in a very long time really

hadn't

given him any pleasure. Despite good intentions, and despite loving Barbara as he felt few people ever loved anybody and feeling that he could be to blame for everything that had gone on tonight, he considered it unmistakable that he could do his wife no good now. He was bad for her. And if his own puny inability to satisfy her candidly expressed and at least partly legitimate grievances was not adequate proof of his failure, then her own judgment certainly was: “You're an asshole,” she'd said. And he concluded that she was right. He

was

an asshole. And he was the other things too, and hated to think so. Life didn't veerâyou discovered it

had

veered, later. Now. And he was as sorry about it as anything he could imagine ever being sorry about. But he simply couldn't help it. He didn't like what he didn't like and couldn't do what he couldn't do.

What he

could

do, though, was leave. Go back to Paris. Immediately. Tonight if possible, before Barbara came home, and before he and she became swamped all over again and he had to wade back into the problems of his being an asshole, and their life. He felt as if a fine, high-tension wire strung between his toes and the back of his neck had been forcefully plucked by an invisible finger, causing him to feel a chilled vibration, a bright tingling that radiated into his stomach and out to the ends of his fingers.

He sat up straight in his chair. He was leaving. Later he would feel awful and bereft and be broke, maybe homeless, on welfare and sick to death from a disease born of dejection. But now he felt incandescent, primed, jittery with excitement. And it wouldn't last forever, he thought, probably not even very long. The mere sound of a taxi door closing in the street would detonate the whole fragile business and sacrifice his chance to act.

He stood and quickly walked to the kitchen and telephoned for a taxi, then left the receiver dangling off the hook. He walked back through the house, checking all the doors and windows to be certain they were locked. He walked into his and Barbara's bedroom, turned on the light, hauled his two-suiter from under the bed, opened it and began putting exactly that in one side, two suits, and in the other side underwear, shirts, another pair of shoes, a belt, three striped ties, plus his still-full dopp kit. In response to an unseen questioner, he said out loud, standing in the bedroom: “I really didn't bring much. I just put some things in a suitcase.”

He closed his bag and brought it to the living room. His passport was in the secretary. He put that in his pants pocket, got a coat out of the closet by the front doorâa long rubbery rain jacket bought from a catalogâand put it on. He picked up his wallet and keys, then turned and looked into the house.

He was leaving. In moments he'd be gone. Likely as not he would never stand in this doorway again, surveying these rooms, feeling this way. Some of it might happen again, okay, but not all. And it was so easy: one minute you're completely in a life, and the next you're completely out. Just a few items to round up.

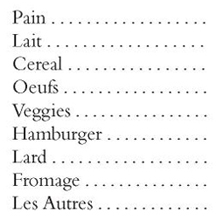

A note. He felt he should leave a note and walked quickly back to the kitchen, dug a green Day-Glo grocery-list pad out of a drawer, and on the back scribbled, “Dear B,” only then wasn't sure what to continue with. Something meaningful would take sheets and sheets of paper but would be both absurd and irrelevant. Something brief would be ironic or sentimental, and demonstrate in a completely new way what an asshole he wasâa conclusion he wanted this note to make the incontrovertible case against. He turned the sheet over. A sample grocery list was printed there, with blank spaces provided for pencil checks.

He could check “Les Autres,” he thought, and write “Paris” beside it. Paris was certainly

autres.

Though

only

an asshole would do that. He turned it over again to the “Dear B” side. Nothing he could think of was right. Everything wanted to stand for their life, but couldn't. Their life was their life and couldn't be represented by anything but their life, and not by something scratched on the back of a grocery list.

His taxi honked outside. For some reason he reached up and put the receiver back on the hook, and almost instantly the phone started ringingâloud, brassy, shrill, unnerving rings that filled the yellow kitchen as if the walls were made of metal. He could hear the other phones ringing in other rooms. It was suddenly intolerably chaotic inside the house. Below “Dear B” he furiously scribbled, “I'll call you. Love M,” and stuck the note under the jangling phone. Then he hurried to the front door, grabbed his suitcase, and exited his empty home into the soft spring suburban night.

5

During his first few dispiriting days back in Paris, Austin did not call Joséphine Belliard. There were more pressing matters: to arrange, over terrible phone connections, to be granted a leave of absence from his job. “Personal problems,” he said squeamishly to his boss, and felt certain his boss was concluding he'd had a nervous breakdown. “How's Barbara?” Fred Carruthers said cheerfully, which annoyed him.

“Barbara's great,” he said. “She's just fine. Call her up yourself. She'd like to hear from you.” Then he hung up, thinking he'd never see Fred Carruthers again and didn't give a shit if he didn't, except that his own voice had sounded desperate, the one way he didn't want it to sound.

He arranged for his Chicago bank to wire him moneyâ enough, he thought, for six months. Ten thousand dollars. He called up one of the two people he knew in Paris, a former Lambda Chi brother who was a homosexual and a would-be novelist, living someplace in Neuilly. Dave, his old frat bro, asked him if he was a homosexual himself now, then laughed like hell. Finally, though, Dave remembered he had a friend who had a friendâ and eventually, after two unsettled nights in his old Hôtel de la Monastère, during which he'd worried about money, Austin had been given the keys to a luxurious, metal-and-velvet faggot's lair with enormous mirrors on the bedroom ceiling, just down rue Bonaparte from the Deux Magots, where Sartre was supposed to have liked to sit in the sun and think.

Much of these first daysâbright, soft mid-April daysâAustin was immensely jet-lagged and exhausted and looked sick and haunted in the bathroom mirror. He didn't want to see Joséphine in this condition. He had been back home only three days, then in the space of one frenzied evening had had a big fight with his wife, raced to the airport, waited all night for a flight and taken a middle-row standby to Orly seated between two French children. It was crazy. A large part of this was definitely crazy. Probably he

was

having a nervous breakdown and was too out of his head even to have a hint about it, and eventually Barbara and a psychiatrist would have to bring him home heavily sedated and in a straight-jacket. But that would be later.

“Where are you?” Barbara said coldly, when he'd finally reached her at home.

“In Europe,” he said. “I'm staying awhile.”

“How nice for you,” she said. He could tell she didn't know what to think about any of this. It pleased him to baffle her, though he also knew it was childish.

“Carruthers might call you,” he said.

“I already talked to him,” Barbara said.

“I'm sure he thinks I'm nuts.”

“No. He doesn't think that,” she said, without offering what he did think.

Outside the apartment the traffic on rue Bonaparte was noisy, so that he moved away from the window. The walls in the apartment were dark red-and-green suede, with glistening tubular-steel abstract wall hangings, thick black carpet and black velvet furniture. He had no idea who the owner was, though he realized just at that moment that in all probability the owner was dead.

“Are you planning to file for divorce?” Austin said. It was the first time the word had ever been used, but it was inescapable, and he was remotely satisfied to be the first to put it into play.

“Actually I don't know what I'm going to do,” Barbara said. “I don't have a husband now, apparently.”

He almost blurted out that it was she who'd walked out, not him, she who'd actually caused this. But that wasn't entirely true, and in any case saying anything about it would start a conversation he didn't want to have and that no one

could

have at such long distance. It would just be bickering and complaining and anger. He realized all at once that he had nothing else to say, and felt jittery. He'd only wished to announce that he was alive and not dead, but was now ready to hang up.

“You're in France, aren't you?” Barbara said.

“Yes,” Austin said. “That's right. Why?”

“I supposed so.” She said this as though the thought of it disgusted her. “Why not, I guess. Right?”

“Right,” he said.

“So. Come home when you're tired of whatever it is, whatever her name is.” She said this very mildly.

“Maybe I will,” Austin said.

“Maybe I'll be waiting, too,” Barbara said. “Miracles still happen. I've had my eyes opened now, though.”

“Great,” he said, and he started to say something else, but he thought he heard her hang up. “Hello?” he said. “Hello? Barbara, are you there?”

“Oh, go to hell,” Barbara said, and then she did hang up.

For two days Austin took long, exhausting walks in completely arbitrary directions, surprising himself each time by where he turned up, then taking a cab back to his apartment. His instincts still seemed all wrong, which frustrated him. He thought the Place de la Concorde was farther away from this apartment than it was, and in the wrong direction. He couldn't always remember which way the river ran. And unhappily he kept passing the same streets and movie theater playing

Cinema Paradiso

and the same news kiosk, over and over, as if he continually walked in a circle.

He called his other friend, a man named Hank Bullard, who'd once worked for Lilienthal but had decided to start an air-conditioning business of his own in Vitry. He was married to a Frenchwoman and lived in a suburb. They made plans for a lunch, then Hank canceled for business reasonsâan emergency trip out of town. Hank said they should arrange another date but didn't specifically suggest one. Austin ended up having lunch alone in an expensive brasserie on the Boulevard du Montparnasse, seated behind a glass window, trying to read

Le Monde

but growing discouraged as the words he didn't understand piled up. He would read the

Herald Tribune

, he thought, to keep up with the world, and let his French build gradually.

There were even more tourists than a week earlier when he'd been here. The tourist season was beginning, and the whole place, he thought, would probably change and become unbearable. The French and the Americans, he decided, looked basically like each other; only their language and some soft, almost effeminate quality he couldn't define distinguished them. Sitting at his tiny, round boulevard table, removed from the swarming passersby, Austin thought this street was full of people walking along dreaming of doing what he was actually doing, of picking up and leaving everything behind, coming here, sitting in cafés, walking the streets, possibly deciding to write a novel or paint watercolors, or just to start an air-conditioning business, like Hank Bullard. But there was a price to pay for that. And the price was that doing it didn't feel the least romantic. It felt purposeless, as if he himself had no purpose, plus there was no sense of a future now, at least as he had always experienced the futureâas a palpable thing you looked forward to confidently even if what it held might be sad or tragic or unwantable. The future was still there, of course; he simply didn't know how to imagine it. He didn't know, for instance, exactly what he was in Paris for, though he could perfectly recount everything that had gotten him here, to this table, to his plate of

moules meunières

, to this feeling of great fatigue, observing tourists, all of whom might dream whatever he dreamed but in fact knew precisely where they were going and precisely why they were here. Possibly they were the wise ones, Austin thought, with their warmly lighted, tightly constructed lives on faraway landscapes. Maybe he had reached a point, or even gone far beyond a point now, when he no longer cared what happened to himselfâthe crucial linkages of a good life, he knew, being small and subtle and in many ways just lucky things you hardly even noticed. Only you could fuck them up and never know quite how you'd done it. Everything just started to go wrong and unravel. Your life could be on a track to ruin, to your being on the street and disappearing from view entirely, and you, in spite of your best efforts, your best hope that it all go differently, you could only stand by and watch it happen.

For the next two days he did not call Joséphine Belliard, although he thought about calling her all the time. He thought he might possibly bump into her as she walked to work. His garish little roué's apartment was only four blocks from the publishing house on rue de Lille, where, in a vastly different life, he had made a perfectly respectable business call a little more than a week before.

He walked down the nearby streets as often as he couldâto buy a newspaper or to buy food in the little market stalls on the rue de Seine, or just to pass the shop windows and begin finding his way along narrow brick alleys. He disliked thinking that he was only in Paris because of Joséphine Belliard, because of a woman, and one he really barely knew but whom he nevertheless thought about constantly and made persistent efforts to see “accidentally.” He felt he was here for another reason, too, a subtle and insistent, albeit less specific one he couldn't exactly express to himself but which he felt was expressed simply by his being here and feeling the way he felt.

Not once, though, did he see Joséphine Belliard on the rue de Lille, or walking along the Boulevard St.-Germain on her way to work, or walking past the Café de Flore or the Brasserie Lipp, where he'd had lunch with her only the week before and where the sole had been full of grit but he hadn't mentioned it.

Much of the time, on his walks along strange streets, he thought about Barbara; and not with a feeling of guilt or even of loss, but normally, habitually, involuntarily. He found himself shopping for her, noticing a blouse or a scarf or an antique pendant or a pair of emerald earrings he could buy and bring home. He found himself storing away things to tell herâfor instance, that the Sorbonne was actually named after somebody named Sorbon, or that France was seventy percent nuclear, a headline he deciphered off the front page of L'Express and that coursed around his mind like an electron with no polarity other than Barbara, who, as it happened, was a supporter of nuclear power. She occupied, he recognized, the place of final consequenceâthe destination for practically everything he cared about or noticed or imagined. But now, or at least for the present time, that situation was undergoing a change, since being in Paris and waiting his chance to see Joséphine lacked any customary destination, but simply started and stopped in himself. Though that was how he wanted it. And that was the explanation he had not exactly articulated in the last few days: he wanted things, whatever things there were, to be for him and only him.

On the third day, at four in the afternoon, he called Joséphine Belliard. He called her at home instead of her office, thinking she wouldn't be at home and that he could leave a brief, possibly inscrutable recorded message, and then not call her for a few more days, as though he was too busy to try again any sooner. But when her phone rang twice she answered.

“Hi,” Austin said, stunned at the suddenness of Joséphine being on the line and only a short distance from where he was standing, and sounding unquestionably like herself. It made him feel vaguely faint. “It's Martin Austin,” he managed to say feebly.

He heard a child scream in the background before Joséphine could say more than hello.

“Nooooon!”

the child, certainly Léo, screamed again.

“Where are you?” she said in a hectic voice. He heard something go crash in the room where she was. “Are you in Chicago now?”

“No, I'm in Paris,” Austin said, grappling with his composure and speaking very softly.

“Paris? What are you doing

here

?” Joséphine said, obviously surprised. “Are you on business again now?”

This, somehow, was an unsettling question. “No,” he said, still very faintly. “I'm not on business. I'm just here. I have an apartment.”

“Tu as un appartement!”

Joséphine said in even greater surprise. “What for?” she said. “Why? Is your wife with you?”

“No,” Austin said. “I'm here alone. I'm planning on staying for a while.”

“Oooo-laaa,”

Joséphine said. “Do you have a big fight at home? Is that the matter?”

“No,” Austin lied. “We didn't have a big fight at home. I decided to take some time away. That's not so unusual, is it?”

Léo screamed again savagely.

“Ma-man!”

Joséphine spoke to him patiently. “Doucement, doucement,” she said. “J'arrive. Une minute.

Une minute.”

One minute didn't seem like very much time, but Austin didn't want to stay on the phone long. Joséphine seemed much more French than he remembered. In his mind she had been almost an American, only with a French accent. “Okay. So,” she said, a little out of breath. “You are here now? In Paris?”

“I want to see you,” Austin said. It was the moment he'd been waiting forâmore so even than the moment when he would finally see her. It was the moment when he would declare himself to be present. Unencumbered. Available. Willing. That mattered a great deal. He actually slipped his wedding ring off his finger and laid it on the table beside the phone.

“Yes?” Joséphine said. “What . . .” She paused, then resumed. “What do you like to do with me? When do you like? What?” She was impatient.

“Anything. Anytime,” Austin said, and suddenly felt the best he'd felt in days. “Tonight,” he said. “Or today. In twenty minutes.”

“In twenty minutes! Come on. No!” she said and laughed, but in an interested way, a pleased wayâhe could tell. “No, no, no,” she said. “I have to go to my lawyer in one hour. I have to find my neighbor now to stay with Léo. It is impossible now. I'm divorcing. You know this already. It's very upsetting. Anyway.”

“I'll stay with Léo,” Austin said rashly.

Joséphine laughed. “

You'll

stay with him! You don't have children, do you? You said this.” She laughed again.