Vietnam (6 page)

Authors: Nigel Cawthorne

THE WAR ON THE GROUND

ALTHOUGH US GROUND TROOPS

had now been committed to a land war on the Asian mainland, President Johnson still hoped to make peace. On 7 April, in a speech at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, he offered Ho Chi Minh a chance to join a $1 billion Southeast Asian development programme in exchange for peace. Hanoi rejected the offer.

Johnson publicly denied that the Marine landings at Da Nang were part of a 'far-reaching strategy' to escalate the war, but the war soon developed a momentum of its own. 1965 began with 23,000 Americans in Vietnam and ended with 184,300. The Da Nang landings were followed by a steady commitment of Marines to I Corps Tactical Zone in the northern provinces of South Vietnam. By mid-April, General William Westmoreland announced a more aggressive patrolling policy and the first clashes between American ground troops and the Vietcong took place. This was part of Westmoreland's belligerent 'search and destroy' strategy. He believe that by hunting down the enemy he could use superior American firepower to kill off Communist soldiers faster than they could be replaced. It would be a war of attrition. But to succeed in such a strategy, more men would be needed.

Soon US troops were pouring into Vietnam. At home in the US, young men of draft-age realised that they risked being sent to a war in a far-flung part of the world where no vital American interest seemed to be at stake. On 17 April 1965, 15,000 students staged an anti-war rally in Washington, DC. To no avail. At a conference in Honolulu on 19–20 April, Westmoreland asked Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara for the US presence to be raised from 40,200 to 82,000 and, on 5 May 1965, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, 'the Herd', which was the US Army's rapid-response unit for the western Pacific, was flown from Okinawa to Bien Hoa to provide temporary assistance to MACV – Military Assistance Command Vietnam. The first US Army combat unit to join the conflict, they should have been relieved by the First Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division in late July. But when the 'Screaming Eagles' arrived, the Herd stayed on.

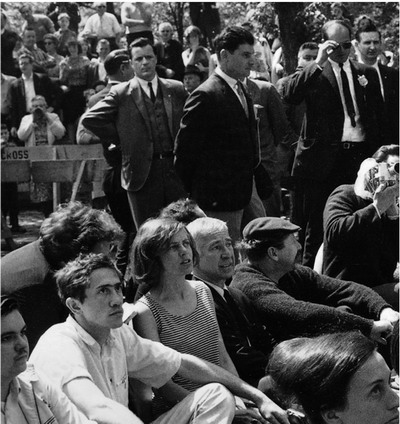

A sit-down peace demonstration temporarily halts the Armed Forces Day Parade on New York's Fifth Avenue, 15 May 1965.

The North Vietnamese high command was not surprised by the commitment of American ground troops. Plans had already been laid for a long war. By June 1965, small contingents of North Vietnamese troops were fighting alongside the Vietcong to test American strength and observe US tactics.

On 21 September, the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) was moved from Fort Benning, Georgia, to An Khe in II Corps Tactical Zone to the south. In October, the whole of the First Infantry Division, 'the Big Red One', was sent to III Corps Tactical Zone, which covered the area around Saigon. And the Americans were not the only ones involved. The government in Canberra was also an advocate of the domino theory and in 1962 the Australians had sent thirty military advisers to South Vietnam. On 4 April 1965, Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies praised the US for accepting the challenge to 'human freedom' in Vietnam and, on 26 May, 800 more Aussies turned up in-country, while New Zealand announced it would send a battalion. By the end of the year, there were 1400 Australians in Vietnam. Their commitment peaked at 7,672; New Zealand's at 552. The British managed to stay out of the war, officially. But there have been persistent rumors that British SAS men served in Vietnam as 'instructors' in Australian and New Zealand SAS units and as part of an exchange programme with the US Special Forces. British citizens who were permanent residents in the US – green card holders – were also eligible for the draft. Americans were also trained in British jungle training schools and the British sent printing presses for the Saigon government to produce propaganda.

An Australian APC in Vietnam, 1967.

Australian Army Minister Phillip Lynch (centre) visits Saigon, accompanied by General Robert Hay (left), commander of Australian forces in Vietnam.

South Korean troops – the ROKs – had arrived in Vietnam in February 1965. They first came under fire on 3 April, by which time there were 200 in country. At the peak of their commitment, 44,829 ROKs controlled a coastal strip of II CTZ. Thailand sent 11,568 troops and allowed American bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance planes to use their airbases. They also allowed an Infiltration Surveillance Center and other US intelligence outfits to operate from their territory. President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines sent 2,000 men. The Republic of China (Taiwan) sent thirty-one and Fascist Spain sent a thirteen-man medical team. More bizarrely, Morocco sent 10,000 cans of sardines, while the Swiss sent microscopes for Saigon University.

Alongside these foreign troops were South Vietnam's forces, the ARVN, who numbered around 620,000 men. But they were not terribly effective. While 90 per cent of American largest-scale operations managed to make contact with the enemy, less than half of ARVN operations did. Officers sold drugs and prostitutes and the desertion rate ran at over twenty per cent. Under Westmoreland's new search-and destroy strategy, the ARVN were relegated to searching for guerrillas in areas cleared by US forces in major operations. But their performance did not improve and their assignment was quickly nicknamed 'search and avoid'. However, the ARVN did have some successes. On 4 April, they destroyed a Vietcong enclave in the U Minh forest, a Communist stronghold in the Mekong Delta to the south of Saigon, killing 238 VC. On 29 April they killed another eighty-four and took thirty-one prisoner, while US air support claimed a further seventy VC dead. And the ARVN claimed another 250 VC dead in the Mekong Delta on 13 August.

On 21 April, the restrictions limiting the Marines to the eight square miles around the Da Nang airbase were lifted, so that they could support the ARVN. The following day another Buddhist monk burnt himself to death publicly in Saigon in protest at the war. The picture was carried in the press around the world. It did nothing to halt the escalation.

On the 24th, Johnson stepped up the bombing campaign and declared the whole of Vietnam a combat zone, meaning that all US servicemen serving there would receive combat pay and get tax advantages. Already the war was costing America $15 billion a year, McNamara announced. Congress quickly approved a further $700 million for the war but on 1 June Johnson asked for another $89 million in economic aid.

Warnings by Cyrus Eaton, a millionaire industrialist newly returned from a peace mission to Moscow, that the USSR would start a nuclear war if US aggression continued were ignored, and a British MP who went to Hanoi in an attempt to open peace negotiations was rebuffed.

The Vietcong stepped up its attacks, scoring major victories. In mid-June, the Vietcong attacked a Special Forces camp and the district headquarters of the ARVN at Dong Xoai, besieging it for four days. In the heaviest fighting so far, the ARVN suffered 900 casualties. The VC were eventually driven off by heavy US air strikes, losing 350 in the fighting on the ground and maybe twice that number in the bombing.

The Roman Catholic opposition forced Prime Minister Quat from office. He was replaced by the flamboyant South Vietnamese air force chief General Nguyen Cao Ky, who was installed as the head of a military regime in Saigon on 18 June. Known for his mirrored shades and his good-looking wife, he was later reported saying that Adolf Hitler was one of his 'heroes'. Ky urged the US to stage an all-out invasion of the North. Politically, this was out of the question. Nevertheless Johnson upped the draft from 17,000 a month to 35,000. The US ground forces also abandoned their defensive posture, and at the end of June launched a major offensive on a Vietcong enclave twenty miles northeast of Saigon, which failed to make contact with the enemy. The VC could fade away at will.

By this time the Marines in Da Nang were getting itchy trigger fingers. They had been trained for aggressive action, not for defence, and had spent five frustrating months filling sandbags and patrolling the perimeter of the airbase. Plagued by mosquitoes, their fitful sleep in the hot oppressive air was disturbed by monkeys setting off trip flares or rattling the rock-filled beer cans that were hung in the wire to warn them of Vietcong infiltrating the base. Patrolling the hills to the west of the base provided little diversion. Loaded with heavy equipment, the Marines dropped like flies from heat exhaustion. Occasionally, they would catch a fleeting glimpse of a VC dressed in the traditional black pyjamas disappearing into the trees and, seemingly, vanishing into thin air. Morale was at rock bottom.

'The Marine mission was to kill Vietcong,' said the Marine Corps General Wallace M. Greene. 'They can't do that by sitting on their ditty boxes'.

Even inside the airbase they were taunted by the Vietcong. At 0130hrs on the morning of 1 July, a sentry was alerted by a noise down by the perimeter wire. He threw an illumination grenade, which brought down mortar fire from the VC. In the midst of the barrage, Vietcong sappers cut through the wire and tossed explosives, destroying three planes and damaging three others. Only one American was killed, but the action attracted worldwide attention. In response, the Marines stepped up their patrolling, to little avail. Trying to find Vietcong among the Vietnamese population, it was said, was like trying to find tears in a bucket of water. Soon the frustration was too much for them. Marines were filmed setting fire to the village of Cam Ne, six miles west of Da Nang, with their Zippo lighters, even though the Vietcong had long since left the area. CBS aired TV footage of the incident on 3 August, sparking international condemnation. It was the first of many such incidents. Two days later, the VC struck again, attacking the Esso terminal near Da Nang and destroying two million gallons of gasoline, nearly 40 per cent of the US fuel supply.

Westmoreland received permission to use his troops as he saw fit in more aggressive action. The American 'tactical area of responsibility' was increased to 600 square miles and US forces prepared themselves to launch new search-and-destroy operations. On 15 August, a VC defector told his interrogators that 1,500 men of the 1st Vietcong Regiment were massing in the villages around Van Tuong, around 80 miles down the coast from Da Nang, ready to attack the new Marine enclave at Chu Lai. For the Marines this was too good an opportunity to miss. But they had to move fast. They decided to attack the VC from three directions simultaneously, surrounding them and pushing them back into the Van Tuong peninsular. They would advance overland from Chu Lai, blocking any breakout to the north. A Marine battalion would make an amphibious landing to the south, while helicopters would land more Marines to the west. The VC would then find themselves trapped with their backs to the sea. This time the elusive enemy would find no escape.

Major Harry Honner, of the New Zealand 161st Field Battery, receives a gift from South Vietnamese premier Nguyen Cao Ky at Nui Dat, 14 January 1967.