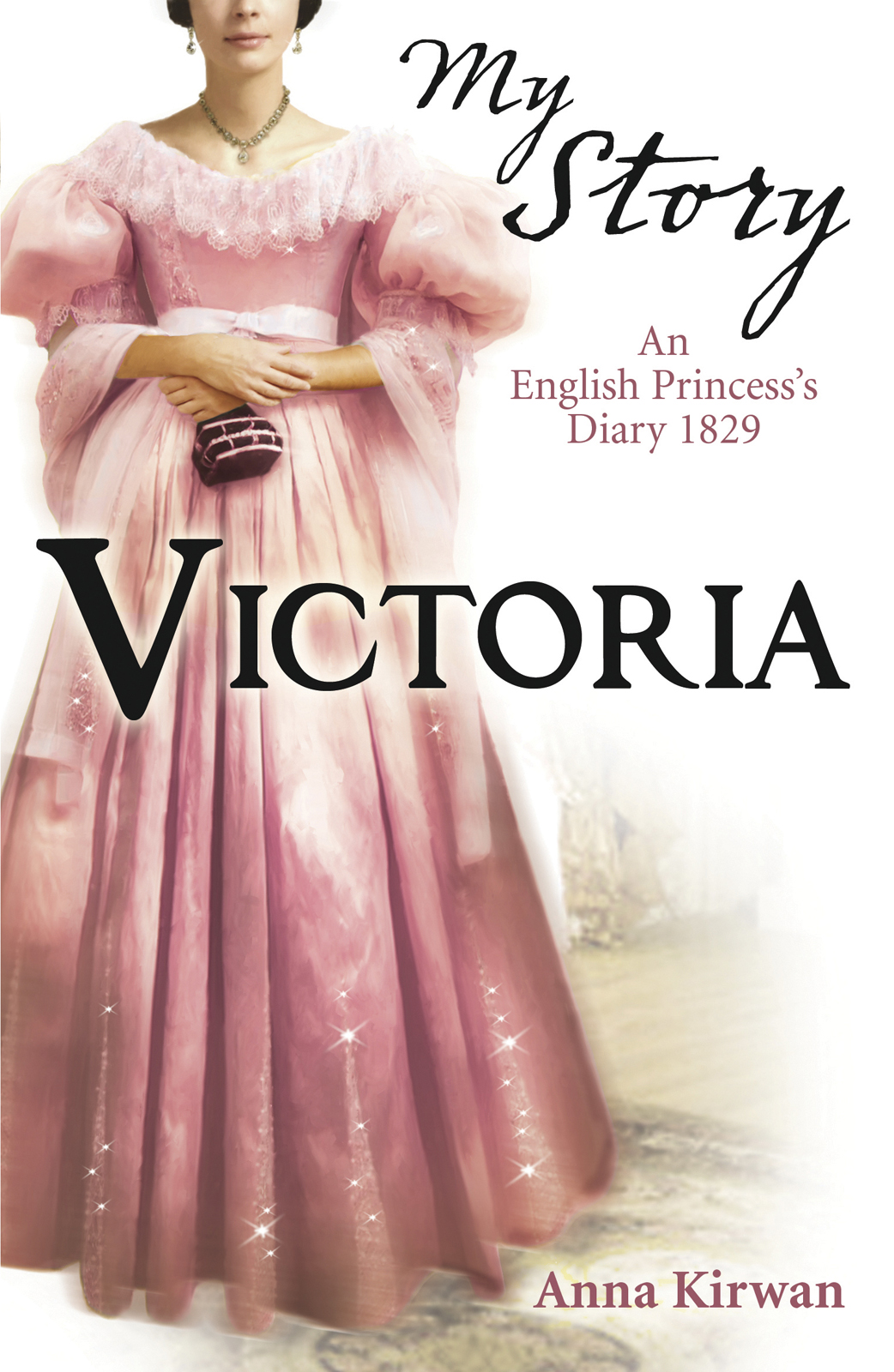

Victoria

Authors: Anna Kirwan

Contents

Â

1 April 1829: Kensington Palace, London, England

25 September: Kensington Palace

8 September: East Cowes, Isle of Wight

The Hanover-Coburg family tree

Â

England, 1829

1 April 1829

Kensington Palace, London, England

This book was not given to me, nor did I buy it with my own pocket money. You might say that I found it, but that would not be completely truthful. It is of a convenient small size, with many empty pages left, having only some lists of cows written in it here and there. The cover is brown, mottled paper, and someone has pasted on a white label. On the label, in very curly letters, it says

Herd Record

.

For, yes, I

stole

the book â from an out of the way, cornermost cupboard in the hall outside the harness room in the stable. I saw the cupboard swinging open once a few weeks ago, when I ducked aside to adjust my undergarments. They were binding me

mercilessly

before my excellent governess, the Baroness Lehzen, and I were to ride out in the carriage. I was itching, so Lehzen bid me go around the corner privately to compose myself and make myself presentable. (Meanwhile, she watched out for anyone who might accidentally interrupt.)

So I did, and there was a little built-in cupboard with the hook-and-eye latch undone. Inside were ledgers, twenty or so, I should say. One was lists of pigs, by name! One was carrier pigeons; one was geese and guinea fowl and such; several were sheep. None was horses â I should have preferred horses. From whose farm these records were, I know not, save, the years marked on them were between 1813 and 1815, four to six years before I was even born.

When Lehzen and I went out today, I recalled seeing the ledgers last time I was in the harness room. I made the same excuse, to hitch up my petticoat and stockings. (I was wearing the blue ones, and in fact, they

were

rather stretched out. I fancy the embroidery on them, though.) I slipped quickly into the back hall. And, although it

was

stealing, I took the ledger. I was dreadfully put to it, to conceal it behind me all the time when I came out. It was tied around my waist with only the sash of my pinafore, and ready to slide loose at any moment!

I don't mean to be unkind, but it almost seemed good fortune for me that Lehzen has had the bad luck to have a sniffling cold this week. She was preoccupied with her nose in her handkerchief on the way back home, and so I managed to fetch in my stolen treasure. I repent

sincerely

at the bitter knowledge that I have broken a Commandment â still, I trust I have done no other person harm by so doing.

Later

I had to hide my little journal, as Lehzen came into the room, looking for her pincushion. I stuck my book and my pen under the tapestry footstool.

The reason I hid this ledger is that I do not wish

anyone

to know that it exists. Really, I must have a place to pour out my curious thoughts privately and sort through them. I never get to be truly alone. Mamma says it would be quite unsafe for a maiden princess to be unguarded by her ladies. So, someone is always nearby â across the room, just out in the hall, in the anteroom. It is not enough that I must sleep in Mamma's bedchamber: I am the only person I know who is not permitted to walk down a flight of steps without holding someone's hand.

Yet sometimes when I am sitting at the window reading or, as now, writing quietly, it is almost as if I am as alone and peaceful as a deer in the forest.

I could be perfectly happy thus, for hours at a time, perhaps, if it were not for the way Certain Persons have of

spying

on me! I suffer greatly from Their lack of trust. (And now, I fear, my feelings have driven me actually to act against my own conscience â I mean, taking this old ledger in order to defy Their wishes. Though this is a journal, not a letter. They didn't forbid me to write a journal. In fact, They didn't forbid me to write letters, only my

own

opinions in my letters.)

Of course, if anyone were to

give

me a pretty little leather-bound journal like the one Mamma's own brother Uncle Leopold keeps, it would only end up being used as a copybook They could read whenever They chose, and then make impertinent remarks. Although I am a princess, His Majesty King George IV's niece Victoria, I am treated this way â with Remarks â too often.

I considered that I might go into the little shop where my art tutor, Mr Westall, stopped the carriage to buy us lemon squashes to drink that hot day we went out landscape sketching. I might in that way manage to purchase one of the little memorandum books â so charming, with a little pencil attached. But They would know I'd done it, as soon as Captain Conroy made me account for what I'd spent. (Why

he

must be Mamma's financial advisor and confidential secretary, I do not know!) I'd either be scolded for spending the money, or

spied on

as to anything I wrote, or

both

.

How do I know this is so? Because Mamma herself took the letter I was writing yesterday to my darling sister, Feodora. She took it away from that bully, Captain Conroy, at least. In the process of doing so, she behaved every inch the Duchess of Kent and Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Saalfeld.

But then she ripped it up and tossed it onto the fire! Which was, of course, burning low for economy's sake. So I had to watch the pages slowly blacken and shrivel. And I had not made a fair copy of it yet, so it was the only one! I had made it quite an interesting letter, too, for Feo, and I regret that I shan't be able to recall all the remarks as I worded them there. I was in a witty mood when I wrote them, not glum as I am now. I am

so

vexed!

“These things you write about us and our System here at Kensington are unbecoming and unkind,” is all Mamma said at first.

Victoire Conroy, that traitorous, cowardly snip, the tale-carrier, was so

horridly

goody-good just then, saying, “I thought it for your safety to tell, Your Highness. Papa says you could be Prey to Others' Interests.” Fine words, from someone who reads what one is writing over one's shoulder!

Toire would do or say anything to get her father to think more about her than about me. And I heartily wish he would.

He

is

not my father

, he is not even in my family. He is only my dear, dead Papa's equerry, his personal officer â a servant, if one thinks about it. But he is a military man, and Mamma admires the way he orders things. And I am to be persuaded that Their concern for me makes it all right for him to raise his voice and make himself frightful, hammering his fist on the rickety old side table with the twisted barley-sugar-stick legs. He pretends he is angry at my supposed enemies, my “rivals” for His Majesty's favour â mostly my own Uncles! â but I feel as though he is angry at me and at Mamma.

“Your wicked Uncle Ernest would be grateful to be able to show this to the King!” he accused me. Oh, he was quite beyond his usual, inattentive

Oh, hmm, oh, hmm, out of the question

! level of temper. Quite! He thundered! “He and the Tories would use it against those of us who have

only your interests

at heart!” The Tories are the political party for old-fashioned Royal rights, and nothing modern.

And Mamma said, “What you put in writing, Vickelchen, can turn up in the newspapers. You do not understand the need to be ⦠to beâ¦

Ach, Gott in Himmel â Stille. Ruheâ¦

”

To which, the baleful O'Hum thundered, “English! English! Speak to her in English! If you want Parliament to ever raise your income, they

must not

think of her as German!”

Mamma still stood straight as a duchess, but her sweet voice was very meek.

“Victoria, you must understand how to keep quiet, that was the word I wanted, how to be â¦

restrained

.”

Child though I am, I do understand â to a degree. The Royal Family is paid for their services to the nation according to the voting of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. They pay for Mamma and me because of my Duke Papa, but I have so many uncles and aunts and cousins, they do not pay us much. Some of my relatives own estates and treasures, and some have to borrow from their friends.

I hear the grown-up people discuss these subjects, but I suppose I am too young to know what is important. I should be seen but not heard.

But â if I can't tell even Feo my true thoughts, how can she advise me as only a sister can, and console me in my troubles as only a sister can? Hohenlohe is so far away! Why had she to marry? It is

very

VERY bad when your dear sister has gone to live in a foreign land.

I would give all the rubies in India to be able to talk to Feo right now.

I hear Grampion the footman coming.

30

30