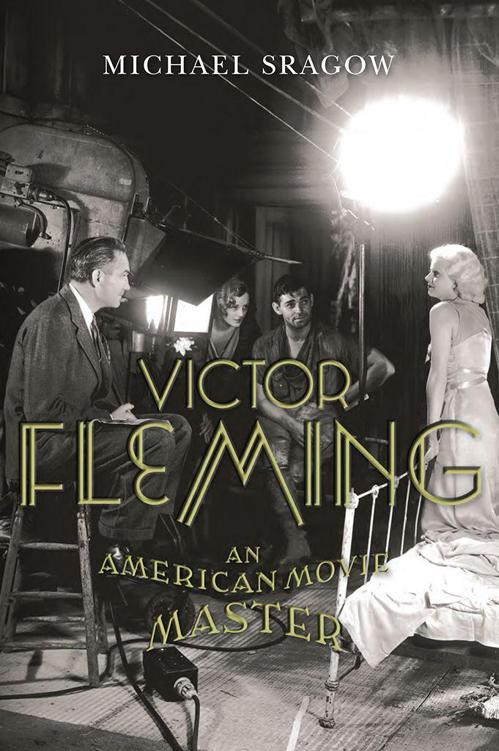

Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics)

Read Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics) Online

Authors: Michael Sragow

V

ICTOR

F

LEMING

V

ICTOR

F

LEMING

An American Movie Master

MICHAEL SRAGOW

Copyright

© 2013 by Michael Sragow

First published in 2008 by Pantheon Books

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices:

The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508–4008

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon Books edition as follows:

Sragow, Michael.

Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master/Michael Sragow.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references, filmography and index.

ISBN: 978-0-375-40748-2 (alk. paper)

1. Fleming, Victor, 1889–1949. 2. Motion picture producers and directors—United States—Biography. I. Title. PN1998.3.F62S63 2008

791.4302'32092—dc22 2008015255

ISBN 978-0-8131-4441-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4443-6 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4442-9 (epub)

Book design by Soonyoung Kwon

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

To

my mother, Kaye Sragow, who taught me how to read; to my wife, Glenda Hobbs, who taught me how to write; and to my friend Pauline Kael, who taught me, by example, to trust my most personal reactions to the movies.

Contents

V

ICTOR FLEMING

INTRODUCTION

The Real Rhett Butler

“ A composite between an internal combustion engine hitting on all twelve and a bear cub”—that’s how a screenwriter once described the movie director Victor Fleming. An MGM in-house interviewer discerned that he had “the Lincoln type of melancholia—a brooding which enables those who possess it to feel more, understand more.” Known for his Svengali-like power and occasional brute force with actors and other collaborators, Fleming was also a generous, down-to-earth family man, even in a sometimes-unfathomable marriage. He was a stand-up guy to male and female friends alike—including ex-lovers. He was a man’s man who loved going on safari but could also enjoy dressing as Jack to a female screenwriter’s Jill for a Marion Davies costume party. After he married Lucile Rosson and fathered two daughters, he reserved most of his social life for the Sunday-morning motorcycle gang known as the Moraga Spit and Polish Club. His ambition in the early days of automobiles to become a racetrack champ in the audacious, button-popping Barney Oldfield mold grew into a legend that he’d really been a professional race-car driver. (Well, he had, but just for one race.) He was one of Hollywood’s premier amateur aviators. Studio bosses trusted him to deliver the goods; many stars and writers loved him.

Victor and Lu Fleming’s younger daughter, Sally, encouraged me to write this book after she read an appreciation of her father that I’d written for

The New York Times

on the occasion of

The Wizard of Oz

’s sixtieth anniversary in 1999. She asked what led me to take on Fleming as a subject. For decades I’d known and loved the half-dozen great movies he’d directed before salvaging

The Wizard of Oz

for MGM and

Gone With the Wind

for the producer David O. Selznick in 1939—movies like

The Virginian

(1929) and

Red Dust

(1932) and

Bombshell

(

1933). But as I told Sally, I’d only recently seen the first film he made after that historic year

—Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

(1941)—and I’d been astonished by its candid sexuality and by how much better it was than its reputation. Sally, who sprinkles frank convictions with spontaneous wit, laughed and said, “

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—

that’s the film that’s most like Daddy.” It didn’t take long to find out that Fleming was a man of more than two parts.

In 1939, the MGM publicist Teet Carle, trying to sell Fleming as a subject for feature stories, noted how remarkable it was, even in what we now consider the golden age of Hollywood, for a director to be “a man like Fleming who has really lived through experiences.” Moviemakers like Fleming, who came of age in the silent era, forged their characters beyond camera range. Andrew Solt, the co-writer of Fleming’s disastrous final picture,

Joan of Arc

(1948), told his nephew Andrew Solt, the documentary maker (

Imagine

), “Victor Fleming’s story is the perfect Hollywood story, from A to Z; it represents the picture business of his time better than anyone else’s.” What the elder Solt meant, of course, was that Fleming’s story wasn’t merely about the picture business—it was about what men like Fleming brought into the picture business.

Fleming was born on February 23, 1889, in the orange groves of Southern California, and became an auto mechanic, taxi driver, and chauffeur at a time when cars were luxury items and their operators elite specialists. During World War I, he served as an instructor and creator of military training films as well as a Signal Corps cameraman, and after it, Woodrow Wilson’s personal cameraman on his triumphant tour of European capitals before the beginning of the Versailles peace conference. Fleming became a friend to explorers, naturalists, race-car drivers, aviators, inventors, and hunters. His life and work are the stuff not just of Hollywood lore but also of American history. It may seem puzzling that he hasn’t inspired a full-length biography until now. But he left no paper trail of letters or diaries, and he died on January 6, 1949, before directors had become national celebrities and objects of idolatry.

Long before sound came into the movies, Fleming had mastered his trade, directing Douglas Fairbanks Sr. in two ace contemporary comedies,

When the Clouds Roll By

(1919) and

The Mollycoddle

(1920). Fleming was part of the team that perfected Fairbanks’s persona as the cheerful American man of action, deriving mental and physical health

from

blood, sweat, and laughs in the open air. The director and the international phenomenon were friends from Fleming’s early days as a cameraman and Fairbanks’s as a star. They became merry pranksters on a global scale, whether hanging by their fingers from hurtling railroad cars or turning a round-the-world tour into one of the first full-scale mockumentaries (

Around the World in Eighty Minutes

). Fleming forever credited Fairbanks with establishing action as the essence of motion pictures. Fairbanks also set his pal an example of the art of self-creation. The son of a New York attorney who abandoned Douglas’s family in Denver when the boy was five, Fairbanks turned himself into a model of dash and vim. Fleming was born in a tent; his father died in an orange orchard when he was four. But he metamorphosed from a Southern California country boy into a Hollywood powerhouse known for mysterious poetic talent, a courtly yet emotionally and sexually charged way with women, and a macho sagacity that spurred the respect and fellowship of men.