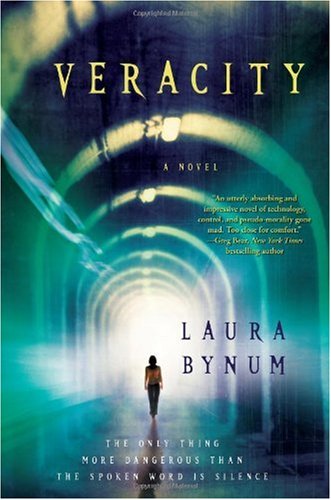

Veracity

Authors: Laura Bynum

VERACITY

VERACIT

A NOVEL

LAURA BYNUM

Pocket Books

Pocket BooksA Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

[http://www.SimonandSchuster.com] www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Laura Bynum

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Pocket Books hardcover edition January 2010

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at [http://www.simonspeakers.com] www.simonspeakers.com.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bynum, Laura, 1968-

Veracity--1st Pocket Books hardcover ed.

p. cm.

I. Title.

PS3602.Y57V47 2010

813'.6--dc22 2009024767

ISBN 978-1-4391-2334-8

ISBN 978-1-4391-5595-0 (ebook)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The day I received the bid on

Veracity,

I'd just had a biopsy on my left breast. Two days later, I received a. confirmation that it was cancer, and b. my contract from Pocket Books. It's been a hell of a ride. What began with a trip to the Maui Writer's Conference (and, while there, winning the Rupert Hughes award for

Veracity

) culminates today in a way-too-brief list of people to whom I am grateful. It is painfully, unforgivably short, considering there are so many of you who were a part of not just helping me heal, but keeping me on track with my work. Were I to list you all, I'd double the size of this book.

Veracity,

I'd just had a biopsy on my left breast. Two days later, I received a. confirmation that it was cancer, and b. my contract from Pocket Books. It's been a hell of a ride. What began with a trip to the Maui Writer's Conference (and, while there, winning the Rupert Hughes award for

Veracity

) culminates today in a way-too-brief list of people to whom I am grateful. It is painfully, unforgivably short, considering there are so many of you who were a part of not just helping me heal, but keeping me on track with my work. Were I to list you all, I'd double the size of this book.

Before going right into my acknowledgments, I should mention that surgery and radiation have cured me. I hope

Veracity

can serve as not just a cautionary tale about retaining our words and knowing the difference between fact and opinion, but also about not losing hope.

Veracity

can serve as not just a cautionary tale about retaining our words and knowing the difference between fact and opinion, but also about not losing hope.

To my family--my generous husband, Eric Bynum, and our extraordinary daughters, Alex, Tea, and Sammy; my three mothers and three fathers, Trudy and Harold Watson, Bev and Walter Clark, and Sheila and Frank Bynum; my courageous siblings, Christina Olshefsky and Patrick Dill; my siblings-in-law, Paul Olshefsky and Joel, Natasha, and Portia Bynum.

To those of my family who've helped from a little farther

afield--my grandfather, Wilbur Long, Joyce Stover, Don Burch, and Mary (Mom Mom) Bynum.

afield--my grandfather, Wilbur Long, Joyce Stover, Don Burch, and Mary (Mom Mom) Bynum.

To my friends--Janet Child, Colleen Cook, Jessica Hall, Barb Johnson, Rhonda and Tony Sinkosky, Carol Ordal, Ronald Rose, Ruth Stoltzfus, Christy Uden, Sonja Wise, Greg Wolf, Tammy and Greg Ziegler, and others too numerous to mention.

To my Illinois and Virginia physicians and caregivers--Dr. Schaap, Dr. Ogan and his bunch of rowdy ladies, Dr. Boyer, Dr. Lander, and Dr. Hendrix and her amazing crew--I was editing throughout my treatment and could not have finished this novel without your support and love.

A special thanks goes out to Dan Conaway who, as Simon so eloquently put it, is my creative beshert. If I could turn your insights into gold, we'd be able to put all our children through college. Also to Simon Lipskar, Sylvie Rabineau, and Jennifer Heddle for their insight into and support of this book.

Most of all, I must acknowledge my Creator who gave me the best diversion of my life on one of its darkest days.

This novel is dedicated to the most spiritually sentient woman I know--my grandmother, Irma Long.

December 23, 1918-July 9, 2009

apostasy

discriminate

ego

fossil

heresy

kindred

obstreperous

offline

veracity

apos-ta-sy

: a total desertion of or departure from one's religion, principles, party, or cause.

: a total desertion of or departure from one's religion, principles, party, or cause.

CHAPTER ONE

AUGUST 4, 2045, EARLY AFTERNOON.

The deeper I get into the prairie, the more I realize that what I've been told about the wastelands is false. The trees here are green. The crops, tall and heavy with corn. There are no black clouds threatening to drip acid onto my car, no checkpoints full of frothing police ready to execute every onerous code they see fit. I haven't seen a Blue Coat since Wernthal. God willing, it will stay that way.

An old farmer is hitchwalking down a line of corn. I see him in my rearview mirror as a blotch of spoiled yellow. This is how our world considers the inhabitants of this land. Spoiled and decrepit, not useful. But neither are they considered clever enough to pose a threat. So they enjoy the otherwise restricted bounty of nature. A wide-open sky. Grass. Neon-free, unfettered space. I envy them this, but only so much. We live in different prisons, but in prisons nonetheless. Theirs is made up of memories of the beforetime. Mine, of concrete walls and security checkpoints, of no birdsong and no breeze.

Fewer line boards are posted alongside the roads out here. Just one every few dozen miles instead of the standard one per block. Posters of non-sexually attractive housewives blink as I drive by.

Stay Happy,

at mile marker 1.

Stay Healthy,

at mile 32.

Remember the Pandemic.

Mile marker 78.

Stay Happy,

at mile marker 1.

Stay Healthy,

at mile 32.

Remember the Pandemic.

Mile marker 78.

Used to be something different.

Honor Those Who've Fallen,

to communicate the whole of it. But the word

honor

got too

many people thinking. The concept sparked a small fire in those of us not quite doused out, and we began to discuss the

dis

honorable things required of all citizens living here, things that didn't get printed on line boards. And so in small, quiet ceremony, in the ripping down of a hundred thousand posters,

honor

had the honor of being our first Red Listed word. We woke the next morning to

Safety First

and

We Don't Want to Go Back to the Way Things Were, Do We?

Honor Those Who've Fallen,

to communicate the whole of it. But the word

honor

got too

many people thinking. The concept sparked a small fire in those of us not quite doused out, and we began to discuss the

dis

honorable things required of all citizens living here, things that didn't get printed on line boards. And so in small, quiet ceremony, in the ripping down of a hundred thousand posters,

honor

had the honor of being our first Red Listed word. We woke the next morning to

Safety First

and

We Don't Want to Go Back to the Way Things Were, Do We?

The countryside is more beautiful than I remember, even like this. Bales of trash instead of baled-up hay. Abandoned farmhouses dotting the land like weeping sores. I can't stand to see their burnt or age-worn structures, or their insides seeping out onto the unmowed lawns. I was born in the country, as were my best memories. I won't desecrate them by noticing these shells of civilization zipping past my car windows. In fact, I'll go faster. It's unlikely Blue Coats will pick me up on the way to my break site anyway. They won't be out patrolling in the heat, in the wastelands where nothing happens. They'll come later when the Fatherboard sees I've gone rogue. It will be the most excitement they've had in months.

Maybe they won't be carrying guns.

Not all Blue Coats get them. Most guns are reserved for the brigade lined up outside the National House like dominoes. Tin soldiers in tidy rows, they flash weaponry used to guard President and his cabinet of Ministers. Keep people from considering assassination, keep those who try anyway from achieving their goal. Guns also go to police assigned to specific jobs. Hunting down runners and the quick dispatch of terrorists.

Not all Blue Coats get them. Most guns are reserved for the brigade lined up outside the National House like dominoes. Tin soldiers in tidy rows, they flash weaponry used to guard President and his cabinet of Ministers. Keep people from considering assassination, keep those who try anyway from achieving their goal. Guns also go to police assigned to specific jobs. Hunting down runners and the quick dispatch of terrorists.

Aside from this ignoble guard, the largely gun-free system has flourished. Fists, elbows, knees, mouths, teeth, the fleshy weapons carried by men, the ones used to inflict more intimate punishments--these broadcast an absolute and terrifying power the business end of a pistol doesn't match. When a Blue Coat exacts a punishment, scars are left and people see them.

I try not to think about the Blue Coats and what may happen to me if I'm caught. At least I will have finally stood up.

I've run in what I wore to the office. A white, long-sleeved linen blouse over a white camisole. A pair of gray tweed pants. Soft leather low-heeled shoes. This would have been so much easier in a T-shirt or a tank top. A pair of jeans, sneakers. From my understanding, the clothes I run in, I stay in for the better part of my training. It might prove stupid, not to have changed, but I'm a Monitor who's just gotten off Red Watch. They would have noticed the clothes gone from my closet or sitting in a sloppy pile in the trunk of my car. They can break into anything they want in the name of security. My home, my vehicle, my computer, my neck. It's how they protect us. From whom, I've long since stopped asking.

The sun is in full bloom above the cracked country road. Sweat beads on my brow, drops onto my cheek, runs down past my collar. It stings my slate, the silver identification module embedded in our necks almost as soon as we're out of the womb. It's barely visible above the skin, with just a line of silvery gray to collect Confederation downloads and provide access to where I am, where I've been, what I've said.

The slate is made of a material I don't understand. The first prototypes, like mine, were refitted as an individual grew. Now they grow with us, like my daughter's. Hers was implanted in her eighteenth month. Most children have theirs put in closer to age two, but she started talking early.

My slate has always itched and when I sweat like this, it feels like an infection. For years I've considered cutting it out, but it's wrapped around the carotid in such a way that it's impossible to remove without bleeding to death. Removing one's slate is the number one method of suicide in the Confederation of the Willing. People who are completely sane in the morning are found at their kitchen tables at night, a cup of coffee in their left hand, a paring knife in their right. I can

understand this madness. Especially if you're older and have memories of the beforetime, like the farmers.

understand this madness. Especially if you're older and have memories of the beforetime, like the farmers.

Other books

To Die For by Linda Howard

Escape 1: Escape From Aliens by T. Jackson King

What the Marquess Sees by Amy Quinton

Unravelled by Anna Scanlon

Beautiful Storm (Lightning Strikes Book 1) by Barbara Freethy

Rebecca's Promise by Jerry S. Eicher

Mornings in Jenin by Abulhawa, Susan

The Trouble With Love by Becky McGraw

The Barbed-Wire Kiss by Wallace Stroby

The Mohammed Code: Why a Desert Prophet Wants You Dead by Howard Bloom