Venice

Authors: Jan Morris

JAN MORRIS

For

VIRGINIA MORRIS

a Venetian baby

This is the third revised edition of a book which I originally wrote in the persona of James Morris.

It is not a history book, but it necessarily contains many passages of history. These I have used magpie-style, embedding them in the text where they seem to me to glitter most effectively; but for those who prefer their history in chronological order, at the back of the book there is a historical index, with dates and page numbers.

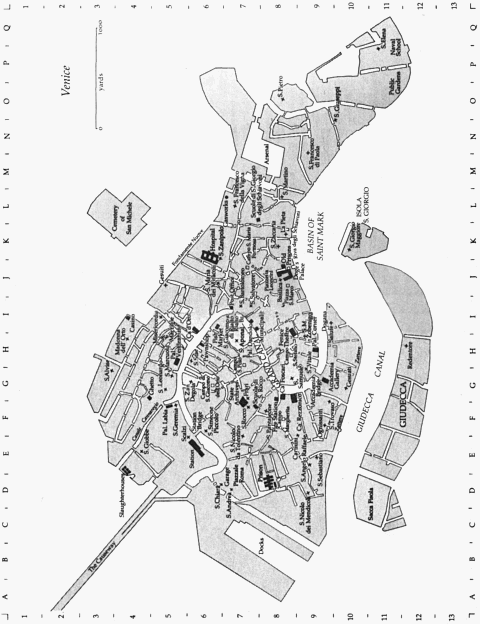

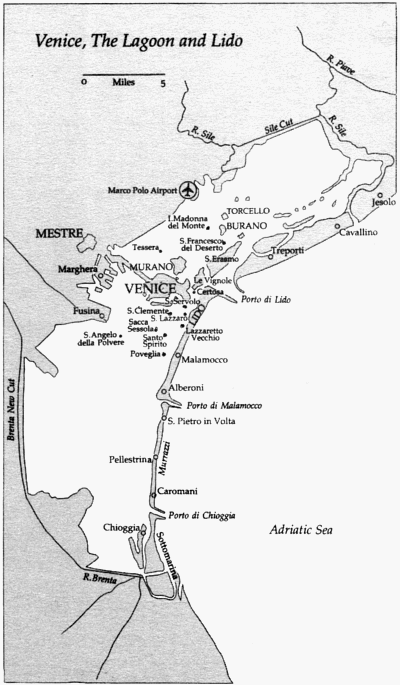

It is not a guide book, either; but in Chapter 21 I have listed the Venetian sights that seem to me most worth seeing, arranged for the most part topographically, and only occasionally confused by brief purple passages. The index contains map references as well as page numbers, and any building mentioned in the book can thus be at least roughly located on the map of the city.

Nor is it exactly a report. When I wrote it, in 1960, I thought it was. I was a foreign correspondent then, and I planned this book as a dispatch about contemporary Venice. When I began to prepare its first new edition, some ten years later, I thought I could simply bring the whole thing up to date, as a newspaper editor reshuffles a page. However as I wandered the canals and alleys with my own book in my hand, I was quickly disillusioned. I soon came to realize that it was not that kind of book at all, and could not be modernized, as I had supposed, with a few deft strokes of the felt-tipped pen. In the edition of 1974, and in its successor of 1983, I changed the details of the book, but hardly touched its generalities.

For it turns out to be nothing like the objective report that I had originally conceived. It is a highly subjective, romantic, impressionist picture less of a city than of an experience. It is Venice seen through a particular pair of eyes at a particular moment â young eyes at that, responsive above all to the stimuli of youth. It possesses the particular sense of well-being that comes, if I may be immodest, when author and subject are perfectly matched: on the one side, in

this case, the loveliest city in the world, only asking to be admired; on the other a writer in the full powers of young maturity, strong in physique, eager in passion, with scarcely a care or a worry in the world. Whatever the faults of the book (and I do acknowledge two or three), nobody could deny its happiness. It breathes the spirit of delight.

So I had mixed feelings in preparing those successive revisions. When I first knew this city, at the very end of the Second World War, it still perceptibly retained that sense of strange isolation, of separateness, which had made it for so many centuries unique in Europe. It was a half joyous, half melancholy city, but not melancholy because of present anxieties, only because of old regrets. I loved this mixture of the sad and the flamboyant. I loved the lingering defiance of the place, bred of empire long before, the smell of rot and age which was so essential to its character, the queerness, the privacy. The neglect of Venice was part of its charm for me, as it had been for so many

aficionados

before. The very echo of a footfall in a shabby lane, the soft plash of an oar beneath a shadowy bridge, could tug my heart and shape my susceptible cadences.

By the 1970s all was different. Because of a great sea-flood in 1966, Venice had captured the concern of the world. The possibility of her extinction beneath the waters, remote though it really was, was seen as an international catastrophe, and from many nations skills and monies poured in not only to save her from drowning, but to restore all her fabrics and preserve her works of art. By the 1980s a new Venice was coming into being, protected, cherished, no longer sufficient to itself, but adopted by the world at large as a universal heritage. While I acknowledged the excitement of this new fulfilment, I could not altogether share it. For one thing, I believed the idea of Venice â my idea of Venice, anyway â to be unreconcilable with the contemporary world. For another, selfishly perhaps, foolishly even, I missed the tristesse. The sad magic had gone for me. Incomparable though Venice remained, I missed the pathos of her decline. I was out of love with her, I thought.

*

Another decade has passed, and here I am revising the book yet again. Am I in love once more? Perhaps, in a resigned, come-to-terms way. The Venice of the 1990s is yet another city, and has moved, I think, beyond nostalgia. Almost overwhelmed though it is by the pressures of mass tourism (sometimes more than 100,000 visitors in a single day), frequently addled by bureaucracy, chafing against the political control of Rome, it has found its new place in the world. All but gone is the curious, quirky Venice of long ago, the Venice of aristocrats and sea-peasants rooted so irrevocably in their own past. Today, I am told, less than 20,000 of the city's inhabitants can claim parents and grandparents born in Venice. Physically it has not greatly changed, but it is a less insular, more prosaic city, and a far more modern one â not a consummation to be sneered at, after all, for in its republican heyday Venice was an epitome of the very latest thing. Safer than any other Italian city, it has become a resort of rich Romans and Milanese, a place of second homes, not so much gentrified as plutocrified. At the same time it has discovered other functions for itself: as the most splendid of conference sites, as a centre of art studies and the techniques of conservation, as a real-estate investment, as a stage for spectacles ranging from regattas to rock concerts.

In short it has, for better or for worse, got over some kind of historical hump. It no longer even aspires to the worldly consequence it once possessed, and with the aspiration has gone the regret. Contemporary Venice is what it is: a grand (and heavily overbooked) exhibition, which can also play useful, honourable, but hardly monumental roles in the life of the new Europe. Can one be in love with such a place? Sometimes I do feel a rush of the old emotion, but it is no longer when some dappled glimpse of a backwater stirs my memories, or I smell the intoxicating fragrance of crumbling antiquity, or feel a pang of poignancy. It is rather when I see the old prodigy once more in full flush, as it were, jam-packed with its admirers, jangling its profits, flaunting its theatrical splendours, enlivened once more by that old Venetian aphrodisiac â success.

Love of another kind, then. I cannot pretend that I feel about Venice as I felt when I originally wrote this book, and so once again I find

that I cannot really revise it. To refurbish my Venice would be false; to rejuvenate myself would be preposterous. The inessentials of this third new edition â the facts and figures that is â have once again been amended. The essentials â the spirit, the feel, the dream of it â I have left unchanged. Though Venice no longer compels me back quite so bemused year after year to her presence, I hope this record of old ecstasies will still find its responses among my readers, and especially among those who, coming to the Serenessima fresh, young and exuberant as I did, will recognize their own pleasures in these pages, and see a little of themselves in me.

TREFAN MORYS

, 1993

Peter Lauritzen, whose own books include

Venice: A Thousand Years of

Culture and Civilization, Palaces of Venice

and

Venice Preserved

, has done me the honour of casting an eye through the previous edition of this book, and helping me to decide what really had to be changed, and what was best left alone.