Vanessa and Her Sister (5 page)

Read Vanessa and Her Sister Online

Authors: Priya Parmar

À:

Miss Virginia Stephen

Hotel Lisboa

Lisbon, Portugal

SERIES 3 NO. 3—HONFLEUR LA CÔTE DE GRÂCE BY EUGÈNE BOUDIN

Trinity College, Cambridge— en route

Friday 21 April 1905

Dear Saxon

,

I was delighted to see you last night, and I apologise for keeping you out so late. I can only imagine that an evening’s deliciousness is soured when gainful employment looms in the morning. Did you make it in to the Treasury Office by nine?

Don’t you think the Goth managed remarkably well last night without dear Vanessa’s capable organisation? What a void those sisters leave when they fly away. Virginia’s incisive, scathing chirps and Vanessa’s level-hipped stability usually provide the contours for a Thursday evening. Do you suppose they know that the evening revolves around them?

Are you free to go to the opera on Tuesday? Do let me know.

Yours

,

Lytton

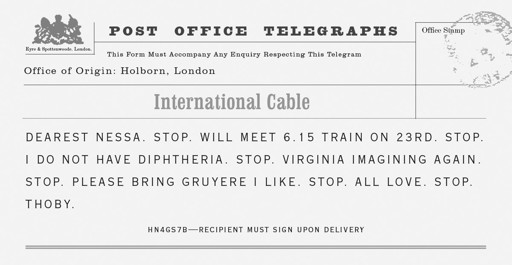

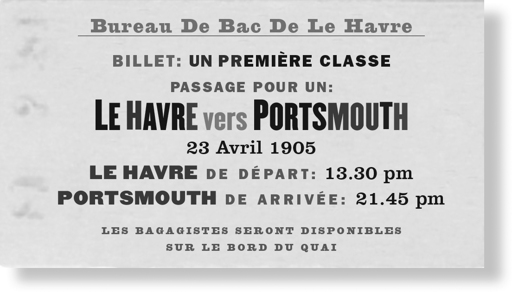

Sunday 23 April 1905—46 Gordon Square

A train a boat a train a cab. There is nothing like the first bath after being abroad.

Later (after supper)

Mr Bell joined us for supper this evening. He and Thoby are still downstairs talking. He asked to see my paintings, quite directly and without preamble—as if he had planned to ask before he arrived. I was sure he was just being polite, but I surprised myself by unpacking the landscapes I did in Honfleur and Cassis. He looked at them, really looked at them, before he spoke. I like that.

Even later (can’t sleep)

A slice of moon lights my room. Bright enough to read by. Bright enough to write. There is deep magic in nights like this. They are different from other, darker, more ordinary nights. I circle back to Mr Bell’s comments. His suggestions were practical. He spoke to me about the unevenness of texture and the disorienting lack of depth in the landscape. He asked if I did it intentionally. Did I? No. I let instinct drive the scene. He waited, unhurried, for my answer. There is a completeness in his attention. It is

not unnerving, but it is not familiar either. It is like a song one hears for the first time and wants to hear again.

Monday 24 April 1905—46 Gordon Square (Virginia and Adrian are back)

“So Snow was not too tiresome in the end?” Virginia asked pointedly. “She wasn’t too annoying or intimate? No awkward silences?”

“No,” I said carefully. Snow’s gentle humour and level common sense have the uniform consistency of spring water. But it is a narrow precipice with Virginia. Too much affection given to someone else and she can topple over, too little and she gloats. “It was quiet and not uncomfortable in the least.” I smoked a steadying breath of my cigarette. “Of course, dearest, I would have much preferred to be with you.”

Later

Virginia received a letter from Mr Maitland, at the

Times Literary Supplement

, in the second post. He wants to call today and discuss her writing. Virginia is hoping he will invite her to be a permanent reviewer. I am crackling with harp-string nerves but trying not to show it.

Writing is Virginia’s engine. She thrums with purpose when she writes. Her scattershot joy and frantic distraction refocus, and she funnels into her purest form. Her centre holds until the piece is over, and she comes apart again.

Later still

Mr Maitland just left. A mixed reception: while her latest book review for the

TLS

has been rejected—not academic enough—she has been invited to try again soon, and Mr Maitland has high hopes for her prospective novel.

Virginia’s mood rocked gently at the tipping point. Relief. She won the day and fell toward the good of the moment.

THE NEW GALLERY

26 April 1905—46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury

T

he exhibition opens today. I submitted my portrait of Nelly to the New Gallery over a month ago but never heard whether it was accepted. Mr Bell says that if it had been rejected, they would have sent it back.

“It probably won’t be there. I think I would prefer it not be there,” I told Virginia over breakfast this morning.

“Nonsense. Of course it will be there, and of course we

want

it to be there,” Virginia said with brisk conviction, buttering her toast.

I was pleased to see that she was eating.

“Nelly loved the portrait. I loved the portrait, and you love the portrait. Ah!” She held up her hand to forestall my protest. “You may not at this precise moment, but at some point between beginning it and now, you have loved it very dearly.”

I smiled at her. Yes, between beginning it and now, there have been moments when it pleased me. It is only now, when others are about to see it, that I doubt its worth.

I sipped my coffee. “It might not be there.”

Later

Virginia set out after breakfast to get a catalogue for the New Gallery. This is Virginia at her best: loving, rational, engaged, sincere.

It

was

there. We stood in the gallery. Watching people watch the painting. It was exhilarating but mixed with an elusive bittersweet I could not place.

Nelly

looked lovelier hanging on that wall than she ever did resting on my easel, but she had grown unfamiliar in the weeks since I handed her over to the gallery. It is true that we do not understand the boundaries and dimensions of what we have created until it is consumed by another. I

loved

being an artist today.

Later (three am—everyone gone)

The talk this evening was about me.

My

painting,

my

exhibition,

my

subjects,

my

work,

my

talent. Lytton, Thoby, Adrian, and Mr Bell went to the New Gallery this afternoon. Adrian and Lytton came down from Cambridge specially.

“On the first day?” I asked surprised.

“Of course on the first day,” Thoby laughed. “When else would we go?”

“Well, you and Adrian, of course—” I said, moved that the others had joined them.

“Pfft,” Lytton said. “Naturally I want to see it first. How else can I tell other people what to think?”

“Desmond and I are going tomorrow,” Saxon said. It was the first sentence he had ever directed at me.

“It was marvellous,” Mr Bell said quietly. He spoke as if we were the only people in the room.

Virginia did not say anything.

28 April 1905—46 Gordon Square (sunny and warm)

This morning my happiness was drenched by real life. I got entangled in a difficult conversation with Virginia. She was determined to discuss the

morality of suicide—one of her favourite fallback subjects, but exasperating on a spring day when good things are happening. I was nervous as we were on the top deck of the Number 8 omnibus and her voice had taken on the specific, tinny shrillness that presages a mad scene—and this was not a good place for a mad scene.

We alighted near Green Park. I decided a long walk home might calm her. The traffic on Piccadilly clanged and kicked up dust, but behind the tall iron fence, the park lay in hushed splendour. Virginia noticed none of it. She was walking quickly, her long skirts flying and her hair slipping loose of its pins. Her small straw hat kept sailing off in the breeze. Twice I had to run after it into the road.

Up we went, along Piccadilly, past Devonshire House with its gilded animal gates, past the great stone cube of the Royal Academy, past the robin’s egg blue of Fortnum and Mason’s emporium. I knew Virginia wanted to stop in at Hatchards bookshop next door but it was better not to risk it. I had to get her home. When I steered her away from the glossy black doors, the tension in her body flared into rage, and I quickly asked the porter at Fortnum’s to hail us a cab.

I know that chewing over a viscous, obstinate question is her way of re-centring a day that is spinning out of her grasp. Trouble is, it takes

my

day along with it.

· ·

A

T HOME, SHE KEPT ON TALKING

; talking without stopping, talking for hours. She did not respond when spoken to and would not turn to look when we called her name. She just continued to talk. When she gets like this, her words rush and tumble like unskilled acrobats, landing up in a heap of broken nonsense.

A few years ago, Virginia talked for three days without stopping for food or sleep or a bath. We were still in Hyde Park Gate, and she sat up in her attic room speaking in low, frantic tones that rose and rose to shake the tall house by the shoulders. That time Virginia’s words unravelled into elemental sounds; quick, gruff, guttural vowels that snapped and broke over anyone who tried to reach her. Her features foxed with

anger growing sly and sharp; her face twisted into something unfamiliar, and her hands bridged into white-boned nests. We waited until the third day before we sent for Dr Savage. A mistake. Virginia spent a month in the nursing home recovering.

Now I know better. After three hours of Virginia’s unbroken talking, we sent for Nurse Fardell to come and administer a mild sedative— a draconian measure as far as Virginia was concerned. I stood outside the door and listened as Virginia evaded the nurse’s starched ministrations. There was a huge glassy noise as the pretty bedside lamp crashed to the floor. Virginia howled, and the nurse spoke to her in a stern, efficient hospital voice.

Thoby came up the stairs with Mr Bell and, joining me in the hallway, asked what was happening. Virginia, not realising that she was in outside company, shrieked, “The Goat’s mad!” from inside her bedroom by way of a reply—her war cry. Virginia hates whispering and always reacts dramatically to sickroom voices. Mr Bell, not the least discomfited, drained the tension clean away by laughing a loud, easy laugh and politely enquiring if we had any other farmyard animals convalescing at Gordon Square.