Vanessa and Her Sister (17 page)

Read Vanessa and Her Sister Online

Authors: Priya Parmar

“Bother the cottage,” Virginia said.

I did not want him to go either but recognised the inevitability. Virginia ignores inevitability and refused to let the subject drop.

“But if you stay with us, you will get to ride home on the Orient Express. To come so close and then miss it? People will think you lack imagination,” Virginia said, her voice rising steeply. I saw Thoby tense. We knew that tone.

“Or, Ginia, they will

commend

me for my imagination. How rare a person it must take to get so close and then

not

go? That takes a rare man,” Thoby said, pulling her to him. “I will miss you and be very sorry not to be here,” he said into the top of her head. She calmed. It was what she was waiting for.

Later (after supper)

We sat in the hotel drawing room. There was an odd assortment of travellers, Violet and us. I poured coffee for Virginia but did not expect her to drink it.

Virginia was sullen but controlled. Thoby had said goodbye to her last. To be saved for last is very important to Virginia.

28 October 1906—Constantinople (hot and close!)

Ill again. Desperately ill. Adrian and Virginia are taking me home.

And

—The train is booked. Adrian was able to re-arrange our seats for tomorrow morning instead of next week.

Later

I managed some soup and a little bread tonight. My fever spikes up quite suddenly, and I lose my way in a thought. We are leaving for London early tomorrow. It will not be an easy trip, and Adrian and Virginia are both worrying about it, which is only making me more uncomfortable.

Clive. Now, when I feel so unsteady and far from the familiar crutches of home, I miss him terribly.

29 October 1906—The Orient Express (late, everyone asleep)

The rocking of the train is soothing as I write this. Everyone is settled into sleeping compartments, and the black, shadowy scenery flashes past the thick glass window. Such a long day.

This morning:

“It is a regular train,” Adrian said, stating the obvious.

Virginia shot him a withering look.

I looked up from my book. “Should it be something else?” I too had been disappointed by the train. Black with peeling gold lettering, the outside was not promising. Inside there are relics of its fabled past. Elaborate Tiffany-style lights and curved divans upholstered in cracked red velvet. At night it can pass for luxurious, but in the inflexible daylight, it looks worn through.

“No, no, I just thought it would be

more

than a train,” Adrian said, clearly wishing he had never made the remark.

Virginia was enjoying his muddle—it distracted her from missing Thoby.

“I know what you mean,” I said, rescuing Adrian. “It is the

Orient Express

. One expects it to be drawn by elephants.”

Virginia rolled her eyes.

THE RETURN

TÉLÉGRAMME

OFFICE OF POSTAL DELIVERY

CONSTANTINOPLE

INTERNATIONAL CABLE

GEORGE. STOP. NESSA ILL. STOP. NOT SERIOUS. STOP. RETURNING EARLY. STOP. ARRIVE NOV 1 DOVER. STOP. YRS VIRGINIA.

GBSW2Q3761—RECIPIENT MUST SIGN UPON DELIVERY

TÉLÉGRAMME

OFFICE OF POSTAL DELIVERY

CONSTANTINOPLE

INTERNATIONAL CABLE

DEAREST SNOW. STOP. RETURNING ILL. STOP. THOB AWAY AND VIRGINIA HOPELESS. STOP. PLEASE VISIT LONDON. STOP. ARRIVE NOV 1. STOP. ALL LOVE NESSA.

GBLH41467—RECIPIENT MUST SIGN UPON DELIVERY

1 November 1906—46 Gordon Square (chilly and wet)

A small, mousy nurse was waiting for us upon our return to Dover. A nurse! George must have arranged it. She held a sign that read “Miss V. Stephen.” “Well, that could mean either of us,” Virginia said. I did not take the bait. I was too tired. The nurse proved more cumbersome than she looked, but at least she could help Adrian sort out his lost luggage.

I was irritated and just wanted to get home. A nurse was all so unnecessary, and I made the mistake of saying so. Virginia gave me a triumphant look. I am always telling her that her nurses

are

necessary. No use arguing. I felt like telling her that if I were raving mad and running all over the house shouting nonsense, as she does, then I would absolutely require a nurse—but I didn’t.

And then we returned here and were shocked. Instead of finding the house empty and Thoby gone to the Lake District, we found him here and very unwell. Not serious, the doctor assured us, but uncomfortable. George, who picked us up from the station, insisted the doctor examine me as well. The doctor announced that I was recovering but not quickly enough and must go to bed at

once

. I did as he asked but looked in and kissed poor Thobs on his feverish head. Virginia is delighted to have us both invalided for a bit. She asked me not to “recover too fast or I won’t get enough chance to spoil you.” The idea does not improve my nerves.

And

—Bother. The doctor also said I had to gain at least eight lbs and brought a weighing machine for me to use every third day.

2 November 1906—46 Gordon Square

Thoby has malaria, a bad case apparently. Dr Thompson just came in and told me (he is replacing Dr Savage, who is away for a few days). The dreadful disease has been nesting inside Thobs for weeks. He must have had fever in Greece but never said. But the doctor has instructed us not to worry. An atmosphere of

calm

will speed his recovery. This was said

to me but aimed at Virginia. She is genuinely shocked by Thoby’s diagnosis but is doing her best, I can tell. I am also shocked. Thoby is the deep ground, and we are the fickle, flexible tree that rests upon it. How can the ground fall ill?

And

—Now wishing I had not cabled Snow to visit as I am not the one who needs looking after.

Saturday 3 November 1906—46 Gordon Square

Clive came again today. He has been stopping in every day, and is the one who insisted poor Thobs go to bed and not to the Lake District. I am grateful.

This afternoon:

“What if I just leave the offer on the table, like a fruit bowl?” he said, sounding amused rather than nervous.

“A fruit bowl? Did you just compare your marriage proposal to a fruit bowl?” I shifted on the sofa, tucking the thick cream blanket around my legs. I am meant to be in bed, but Snow allowed me down to Thoby’s study. I am glad she is here, although her unruffled calm is annoying Virginia.

“Yes. Why not? Fruit symbolises the offering of love and devotion,” Clive said with a look of wry dignity.

“And knowledge. Fruit gets women into trouble,” I said carefully.

And

—Weighed every other morning now. Gained one lb. As I get weighed in my nightgown, I have moved the weighing machine into my sitting room.

Later—back upstairs

Clive has been considering my suggestion that he go away for a year to jolt me into understanding myself. Perhaps Paris. As I heard him talk about it, I felt a shiver of jealousy. Good. I will nurture that. Perhaps it may grow into something useful. But he will not leave now. He will not leave Thoby while he is so ill.

5 November 1906

Strache

,

Get down here. Bring Saxon. Get Desmond. The Goth is ill, and while the doctor swears it is malaria and just miserable, rather than threatening, I am beginning to think the man is a charlatan and want to get a second opinion. Goth doesn’t look like a man with malaria. His face is waxy and slack, and his great bear’s body has rather sunk in on itself. Looks bad.

The girls are all right. Virginia is fixated on what he eats and sees each spoonful of coddled egg and clear broth as a sign of immediate recovery. Nessa herself is very ill and has not been allowed to see him. She is a quieter, fragile Nessa, and I only love her more. Adrian is pragmatic and dogmatic and hell-bent on not questioning the doctor. Frankly, I am surprised these Stephens are not panicked, given their history of losing people. In over my head, Strache. Hurry.

Yours

,

Bell

8 November 1906—46 Gordon Square (early—everyone asleep)

“Dearest?” I touched his foot so he would know I was there. I was not meant to see him, but I had to.

“Nessa,” he said, turning his face towards me. His eyes were open and glassy. He had not been sleeping after all.

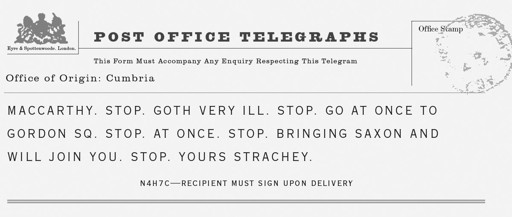

“They are all here. Lytton, Saxon, Desmond, and Clive. They have all come to see you.”

I knew the arrival of his friends would mean much to him. His face lit with a faint smile. Like a pale pool of gaslight on a fogged street.

“Good men, Nessa. They are all good men,” he said, his voice dwindling as he used up his strength. His chest rose and fell rapidly with the effort. “Bell. Bell is especially good.”

“Yes, dearest,” I said, taking his hot, papery hand. He closed his eyes, and we fell into the comfortable silence of siblings.

· ·

I

THINK ABOUT THE

many times I have heard Thoby and his friends discussing the nature of good. By whose standard should good be measured? By whose count should good be counted? Thoby’s good is good enough for me.

Later—early evening (my sitting room)

“Virginia.” I struggled for patience. “All I know is what you know and what the doctor told us. I did not receive any more information than you.”

I closed my eyes. Keeping them open is very difficult these days. My appendix appears to have improved, but my strength refuses to return. I am meant to be taking the rest cure but find bed more exhausting than not bed. And so I get up. I bathe but then get into my nightgown and blue silk wrapper again. I never manage to get my hair up and just leave it in a long braid snaking down my back. Virginia came in today and tied a black ribbon at the bottom to hold it together.

I am sure it was just the travelling that wore me out and nothing more sinister. Dr Thompson has prescribed an invigorating tonic for nerves, and rest, complete rest, which is of course a huge bother.

“Virginia,” called Clive from the hall. “Virginia, she is meant to be asleep. Come away, please.”

This is how it is now. Clive roams all over the house like a member of the family. This morning I saw him upstairs without his jacket—such informality would have been outrageous a month ago. He speaks to Dr Thompson about the medical treatments and then discusses them with us. We have come to rely on him. Yesterday Snow went to

him

to ask if he thought she was still needed or if she ought to return home. It is probably best that she go, as she gets on Virginia’s nerves. Clive told Snow he would send a telegram at the first sign of trouble, and in the meantime he promised to look after us and so drove her to the station. Should I mind such intimacies? I find I do not. I am relieved. Yesterday I found him and Virginia discussing enemas in the drawing room: glycerine versus turpentine—dear God. Had no idea what to make of it and so returned to bed.