Valleys of Death (10 page)

Authors: Bill Richardson

“That is the kind of shit that is going to get us all killed,” I said, clearly enraged.

“I got it, Richardson. Let it go and I'll take care of it,” he told me.

Back at the company assembly area, the men rested on their packs, some dozing, others just staring blankly into space. I took a moment to look at what was left of the company. We'd gotten some replacements, but the company had only sixty-eight men. Five or six had been wounded and returned to the line still bandaged up. One of our machine gunners had been wounded three times and was also back. If this was winning, I didn't want to lose.

While we rested, I noticed a new group of replacements. South Korean conscripts. It was bad enough to come into a unit as a replacement. I couldn't imagine being a Korean and winding up with an American unit.

Vaillancourt brought six South Koreans to me.

“Your new guys,” he said.

The South Koreans looked at Vaillancourt.They didn't understand a word and looked scared to death. Dressed in American fatigues, they cradled old M-1 rifles and had small backpacks. They were skinnier than us, but that was changing since we were still on half rations.

I thanked Vaillancourt and smiled at my six new soldiers. They were from the Korean Augmentation to the U. S. Army (KATUSA) program. KATUSA soldiers were young men picked up in the larger cities, given a couple of weeks' training and assigned to American units. Looking over the group, I spotted one that I seemed to connect with. He was stockier than the others and had bright, alert eyes. I tried to talk with him and he just smiled at me. I named him Tony because it sounded similar to his Korean name, and I explained to him that I was calling him that. He shook his head yes and repeated “Tony” and pointed to himself.

I separated them and assigned each small group to my two squads. Tony and the others were mainly used as ammunition bearers. We loaded them up as pack mules and they became an integral part of our firepower.

We lost two of the new Koreans the first day. One was killed and another badly wounded. A couple of days later, I received a replacement for one of them. Tony took charge of him right away. By now, he'd proven to be the most capable and the de facto leader. We had come up with a simple shorthand using English words and hand gestures.

Despite the language barriers, the Koreans fell right in with the rest of us. When we marched, they kept up. When we fought, they stood their ground too. But we found out early on that our C rations were too concentrated for their systems and they just couldn't eat them. The canned meat and beans upset their stomachs. After a lot of trial and error, we finally found that they could handle rice and vegetables. I made sure the section saved those rations for the South Koreans. But as did all soldiers, they liked chocolate.

Not long after Tony arrived, Captain McAbee was promoted to battalion operations officer. He would make a good operations officer because he certainly understood the problems at the company level. Lieutenant Paul Bromser replaced him as company commander. Unlike McAbee, Bromser was quiet and seemed unsure of himself.

Early in the morning the company joined a coordinated attack against Hills 401 and 307. We managed to sweep the North Koreans off the hill, but not without heavy casualties. Early in the attack Lieutenant Brown, the leader of the First Platoon who'd begged for more firepower days earlier, was seriously wounded and taken off the hill on a litter. “Old Firepower Brown” was the last of the platoon leaders who'd left with us from Fort Devens. He would be missed. He was one of the best. There were fewer and fewer soldiers from Fort Devens. Luckily, in my section, I still had Walsh, Hall and Heaggley.

The North Koreans were well entrenched on Hill 312. The mountain was critical terrain because it overlooked the approaches to the Naktong River. I sent Walsh with the company, and I took Hall and a light machine gun section to the left side of the North Korean's position. Bromser figured we would distract the North Koreans and help suppress their fire while the company advanced.

The hill was steep, and it took us a while to weave our way up the scrubby brush. I could hear the men straining against their loads. We'd almost made it to the top when I heard a single shot. Hall crumpled to the ground.

Everybody else dove to the ground. I crawled over to him. He was clutching his stomach and I could see blood seeping through his fingers. It had to be a sniper.

His skin was gray and he was in shock. Hall was in serious condition and we had no medic with us. I knew he wouldn't make it down the hill. I also didn't have men to spare, but I called over two of my new guys.

“Drop your ammo and get him back down the road,” I said.

They rolled Hall onto a poncho and hurried down the hill, staying low and out of the sniper's sights. Without me saying a word, Heaggley took over Hall's squad, and we both picked up the ammo that had been dropped.

We kept moving up the ridge and into a depression protected by a knoll.The sniper kept shooting, but hadn't hit us again. Poking my head up over the lip of the hill, I called Heaggley and told him to move up to my position.

“Come around the knoll to the left and join me and the machine gun squad,” I said.

The knoll offered some protection from the sniper. I crawled back into the hole and was lying on my back when Heaggley came over the top of the hill. I saw a puff of smoke right in the front center of Heaggley's helmet and he fell backward behind the hill. The sniper had shot him right between the eyes. I screamed for his squad to come around to the left, not over the top. I was waiting, but no one came. All of a sudden the first guy to come around the knoll was Heaggley.

“Jesus, Rich, I thought you hit me with a rock,” he said.

Pulling off his helmet, he showed me the hole. It was square in the center of the helmet. The bullet had entered and followed the helmet around, taking a nick out of Heaggley's ear and cutting a deep groove into his helmet liner.

“You're a damn lucky guy,” I said. But our smiles were short-lived.

One of the machine gun crew was not as lucky. He was dead.

From our position, we raked the North Korean positions with machine gun and 57 fire as the company charged up the hill. When the company joined us, the ridge was littered with the bodies of North Korean soldiers. We estimated at least two hundred dead, wounded or captured. We also found a massive weapons cache.

I saw a group of prisoners nearby. It was obvious that they had been in the field for a long time. Their uniforms were ragged and dirty. Caught in their holes or lying in front of our position, they had very little food on them. They were fanatical during an attack, but when we captured them they appeared childlike, very docile and scared. It reminded me of the photographs of the Japanese I had seen toward the end of World War II.

A few days later, we got the news on the Inchon invasion. General Douglas MacArthur conceived the bold amphibious landing far behind enemy lines on the west coast of South Korea in hopes of taking the war to the North Koreans. President Truman and the Joint Chiefs had reluctantly approved the plan, and the First Marine Division and the Army's Seventh Division went ashore on September 15.

The North Koreans only had about two thousand second-rate troops in the port city. The landing surprised the North Korean Army and they were quickly overwhelmed. Around Pusan, the impact was minimal. We had our own little part of the world to contend with.

Timeline to 38th parallel.

Constructed by author based on daily battalion situation reports from the National Archives

Constructed by author based on daily battalion situation reports from the National Archives

Over the next few days we continued to attack to the west. It was a knock-down, drag-out slugfest. The North Koreans attacked us with abandon and tried to overwhelm us with numbers. They were fanatical. One regimental commander said after the war that the North Koreans had “no consideration for loss of life. They have no hesitancy in losing five hundred lives to gain a small piece of ground.”

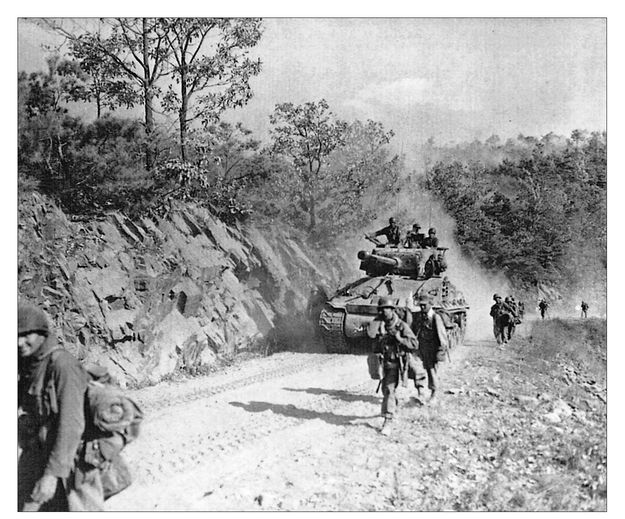

8th CAV Regt. tanks and men close in on the enemy.

National Archives

National Archives

It took us three more days to take two more North Korean positions. We uncovered large ammunition caches and killed seventy-two and captured two hundred. All at a great price. I lost two more men, and the company suffered a total of four killed, with thirteen wounded. The losses reduced our strength to around fifty-three men.

We were prepared to continue the attack, when we received orders to move to the road and start moving back east to the “Bowling Alley.” When we got to the road junction, we saw that cooks had set up right on the side of the road and were passing out coffee and cinnamon rolls. It might as well have been a banquet. I never forgot the taste of that hot coffee and those cinnamon rolls.

The enemy was now on the run and we held the river line. The morale went sky high. We loaded on trucks near Tabu-Dong and headed north. Only three weeks earlier we had withdrawn south through the North Korean lines in the same vicinity.

Hard to believe.

CHAPTER EIGHT

PURSUIT TO THE 38TH PARALLEL

Hunkered down in my foxhole, I stared at the brownish water of the Naktong River and waited to cross.

For weeks, the river had been the line we had to hold, but now we prepared to cross it and finally take the war to the North Koreans. I heard the rumble of aircraft engines high above. I rolled over on my back, looked up, and there were six bombers flying low overhead. When they were a short distance from us, I watched as the bomb bays opened and to my surprise they released their bombs. It looked like they were going to drop them right on us. I was frozen in place as the bombs rolled out of the bay and sailed over the top of our position, crashing into North Korean positions on the other side of the river. I hoped they'd hit home since in a few hours I knew we'd be fighting through that area.

On the backside of the hill we occupied there was a pond. We could go down to the pond by platoon, and in my case section, and clean up. I peeled off my dirty and tattered uniform and waded into the bourbon-colored water. The warm pond felt great, and when it hit my thigh, I just sat down and let it swirl around me. Those brief seconds in the water were the best I'd felt in a long time. Standing up, I started to clean up. My skin was bruised and scraped. My joints ached, and after being on half rations, I was rail-thin. Wading back to shore, I pulled on clean fatigues from a pile left by the supply sergeant. Nearby, some of the guys were standing by a case of beer. Walsh saw me and handed me one. It was warm, he said, but tasted good. Greenlowe joined us. I handed him a beer. We both opened our beers and took a long pull. It was the best beer I'd ever tasted. I looked at Greenlowe to see his reaction; it was actually his first beer and he made a funny face. I slapped him on the back as Walsh and I both laughed.

Just before midnight, we headed for the ford. Engineers and civilian workers had built a pontoon bridge, and by the time we got there it was jammed with tanks, jeeps, trucks and men. As we walked along the road, we passed long lines of trucks waiting on the side. The drivers stood nearby smoking and talking. They knew what we all knew. This was the old Army game of hurry up and wait. We worked our way down the road and finally pulled off to the side near the river. It didn't bother me. I was clean, my uniform was clean, and I could still taste that beer.

At three the next morning, it was our turn to cross. We had a mission to capture and secure a small town a few miles north of the crossing site. As we hustled down the road, I saw what looked to be thirty North Korean artillery pieces lined up hub-to-hub. True to Soviet doctrine, they were massed and well forward. And caught totally by surprise when we breached their defense line. They looked like they were waiting for trucks or horses to tow them north. The tide had definitely started turning in our favor.

Other books

Come Unto These Yellow Sands by Josh Lanyon

How to Murder the Man of Your Dreams by Dorothy Cannell

The Last Letter From Your Lover by Jojo Moyes

Darling Georgie by Dennis Friedman

The Death at Yew Corner by Forrest, Richard;

A Cornish Christmas by Lily Graham

Breaking the Nexus (Mythrian Realm) by Avalon, Lindsay

A Different Christmas (University Park #5) by C.M. Doporto

1014: Brian Boru & the Battle for Ireland by Morgan Llywelyn

Spoils of Eden by Linda Lee Chaikin