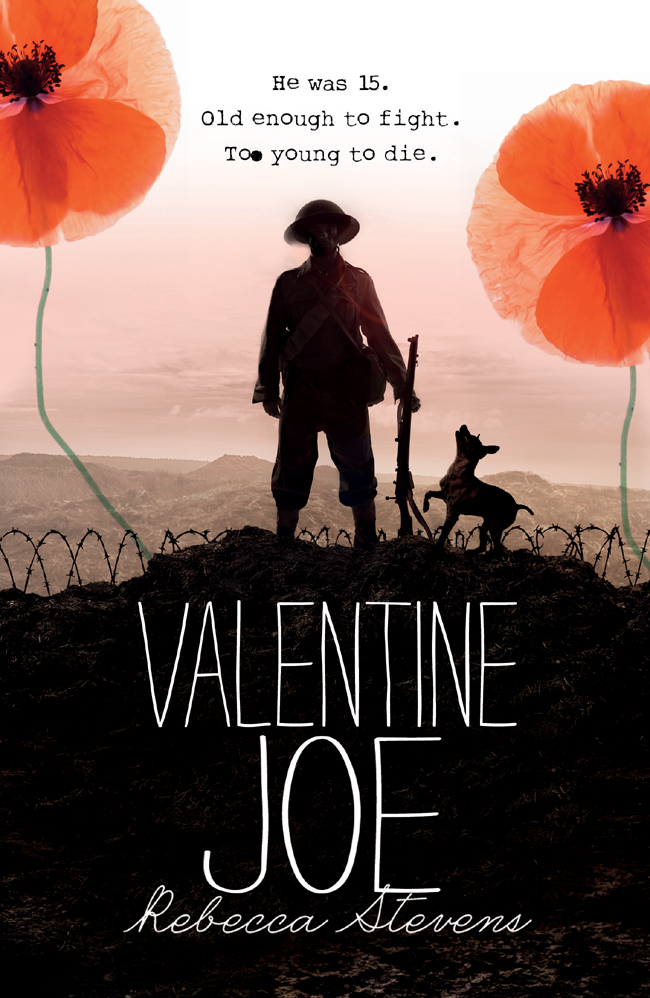

Valentine Joe

Authors: Rebecca Stevens

From the Chicken House

Can we ever imagine life for ordinary âJoes' in the chaos and confusion of the First World War trenches? Well, here in this moving, heartbreaking and warm story Rebecca Stevens does just that â she takes a modern young girl back to meet a boy soldier and his dog. They learn a lot together â but more importantly they help each other come to terms with what's happening in both their worlds, when death becomes part of everyday life.

Sorry, I couldn't help crying. IT MUST NEVER

HAPPEN AGAIN!

Barry Cunningham

Publisher

2 Palmer Street, Frome, Somerset BA11 1DS

www.doublecluck.com

Contents

In memory of my grandfather, Fred Thompson,

and the men and boys of all nations

who didn't make it home from the Great War.

âIn Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.'

John McCrae

âIn Flanders Fields'

, Essex Farm 1915

I

t was the day before Valentine's Day and Rose was on a train, speeding through the misty Kent countryside with her passport in her bag, her phone in her pocket and her grandad on the seat opposite, snoring gently. Rose hoped he wasn't going to dribble.

She stifled a yawn and looked around the compartment at the other passengers, trying to imagine who they were and what their lives were like. She often did this when she was sitting on a train or bus and had nothing else to do. It stopped her getting bored.

Or thinking about other stuff.

Her eyes rested on a smartly dressed woman across the aisle, working on her laptop. She lived on her own, Rose decided, in an amazing flat overlooking the river, but secretly longed to move to the country and breed guinea pigs. And the smug, pink-faced businessman opposite, who looked like he'd been over-inflated with a bicycle pump â he didn't know his teenage daughter had just got her

tongue pierced and his son was keeping a snake in a shoebox under his bed. The young couple with backpacks and blond dreadlocks, whispering to each other further down the carriage, were on the run from the police. Rose was just trying to decide what crime they might have committed when the girl looked up and caught her eye.

Rose stared down at her book, cheeks hot with embarrassment. She seemed to spend a lot of time feeling awkward these days. She'd felt excited that morning though, when Grandad had picked her up and they'd gone swinging through the early-morning streets in a cab, heading for St Pancras International. She'd felt like someone different, someone who got on trains and set off to foreign countries all the time. Someone who found it easy to talk to boys, went to loads of parties and didn't spend so much time staring out of her bedroom window or making up weird stories about strangers on trains. Someone normal, in other words.

Someone happy.

Not that Rose was

un

happy. She didn't go round bursting into tears in Tesco or anything like that (although she did once feel like crying when a friendly bus driver called her âsweetheart' and told her to have a good day). It was just that since it happened, since Dad died, Mum had been so wrapped up in her own sadness that you couldn't get near her. Rose felt the same in a way. It was like she and Mum were in two separate bubbles, floating away from each other in space. It had been nearly a year now, and Rose still felt a bit â

alone.

She wasn't really alone, not literally. She

did

have Mum, of course she did, and Grandad. And her two best friends, Ella and Grace, had been extra nice to her.

But, but, but . . .

Rose's dad was thirty-eight when he died. He had sticky-up hair and a crooked grin. For months after, Rose had had the same dream. She'd be asleep in bed â in the dream â and there'd be a knock at the front door. And she'd wake up â still in the dream â and run down and open the door and there he was. Dad was there, looking just the same. And he'd grin and shrug and say: âIt was all a mistake! I'm here! Here I am!' And he'd hold out his arms and she'd feel the roughness of his jumper on her face and dissolve into the old familiar smell of soap and toast and bicycle oil.

And then she'd wake up, for real this time, and realise it was a dream. Dad had gone and she was alone in her room with the grey London morning seeping through the curtains and no one but her old teddy bear for company. She'd hear Mum getting breakfast downstairs and even the clatter of the plates would sound lonely. Then Rose would get up, get dressed, get on the bus to school. And at the end of the day, she'd come home and there'd still be no Dad, and Mum would still be silent and sad, and nothing would ever change, ever ever ever.

That was when she wanted to go back into the dream. And stay there for good.

Grandad made a little sound in his sleep and shivered. One of his hands was on the table between them: squarecut nails, brown spots on the back, veins standing out. Rose's heart clenched as she looked at it. Grandad was so

old

. He wouldn't be around for ever.

Rose couldn't bear to think what a world without Grandad would be like, so she reached out a hand to wake him. She wanted him to be there with her, to talk about normal stuff, make her laugh, start embarrassing conversations with

strangers, anything. Then, as a funny little half-smile passed across his sleeping face, she changed her mind. She'd let him sleep. Her dad was his son, his boy. He missed him too. And perhaps, like Rose, he was dreaming about a knock on the door.

So Rose got out her phone instead and scrolled through the names.

Home

,

Ella

,

Grace

,

Grandad

,

Mummob

,

Dadmob

. . .

She clicked on

Dadmob

.

No one knew she still sent him texts. Not Mum, not Grace or Ella. Not even Grandad. It was her secret.

She'd sent the first one the day of the funeral. Everybody had come back to the house after the service for cups of tea and sandwiches, and Rose had sat by herself in the chair where Dad always sat to watch the football, a small knot of unhappiness, while the room, the guests, swirled anti-clockwise around her. Someone had dropped a salmon sandwich on the carpet near Dad's chair, which someone else had trodden on (the smell of tinned salmon still made Rose feel sick). She'd got out her phone to try and look busy, and scrolled through the numbers in her contacts.

Home

,

Ella

,

Grace

,

Grandad

,

Mummob

,

Dadmob

. . .

Dadmob . . .

Dadmob . . .

Dad . . .

She couldn't bring herself to delete it. That would make it real, the fact that he was gone. Final. So, sitting there, in his favourite chair, she'd sent him a text instead. Five words:

Hello dad it's me rose

Then a kiss, just one:

x

The thought of the words flying up through the air had made her feel a tiny bit better. So she'd been doing it ever since. She didn't write anything important or weird, just the usual stuff:

I'm on the bus and I'm bored x

History exam today argh x

Sometimes she just put:

xxx

Rose wondered what happened to all the texts she sent. She pictured them flying up, suspended against the blue of the sky for an instant before slithering down and ending up in a drift at the bottom like dead leaves. Then Dad would come along and stare at them for a second, before crouching down to sift through them and reassemble her messages:

I miss you

I'm sad

I don't want to be here if you're not

Sometimes she wondered how she'd feel if she got a reply. It'd probably be from someone who'd taken over the number:

Who r u? Stop txtng me freak!

âFnuff!' Grandad made a loud snort and woke himself up. He looked around accusingly as if he didn't know where he was and glared at the woman working on her laptop before his eyes came to rest on Rose and his face softened. For a second he looked so much like Dad that Rose felt her eyes prickle.

âAll right, Cabbage?'

Grandad was the only one who called her that now. Rose shook her head at him, pretending to be cross.

âYou were snoring, Brian.'

When she was little Rose had heard her grandma calling Grandad by his first name and had copied her. This amused everyone so much she'd kept it up.

âWhen you get to my age snoring's one of the few pleasures you've got left,' he said, producing a plastic box from his bag. âHave a biscuit.'