Urchin and the Heartstone (19 page)

She found she could repeat it by heart. Mother Huggen had to say it, too. Then Crispin asked, “What does it mean, Brother Fir?”

Fir blinked, stood up, and shook his ears briskly. “Dear King Crispin,” he said, “it’s quite enough to receive a prophecy without being expected to understand it. There it is.” He smoothed down his old tunic which, Needle noticed, was looking more frayed and threadbare than ever. “We must be alert, of course, but I do hope that we’re not all going to go off looking for traitors. The king was quite right. Mistrust is poisonous.”

“You may all go,” said Crispin, “except you, please, Padra.” It seemed to Needle that there was a new brightness about him. The prophecy must have given him hope. She pushed the plate firmly toward him before trotting from the chamber.

“Will you please finish the royal breakfast?” said Padra. “Or do I have to cram it down the royal throat?”

“I’ll eat it,” said Crispin, taking a pawful of hazelnuts. “A prophecy, Padra! What do you think it meant?”

Padra shrugged. “If Fir doesn’t know, you can’t expect me to. But it makes me sure that Urchin will come back.

Over the water.

Do you suppose ‘the Secret’is Urchin? It might be, as we don’t know anything about who he is.”

“Or could it be Juniper?” said Crispin. “But if we knew what it was, it wouldn’t be a secret. I’ve had Russet and Heath organizing searches for Juniper, but he’s not on the island. I hope he’s not a traitor, but he’s another one we know nothing about. A mystery, like Urchin.”

Needle liked to be busy, especially now, as it took her mind from Urchin. She hurried down to the shore, accompanied by Gorsen’s friend Crammen, who insisted on telling her again that the best kings were always hedgehogs.

After a little beachcombing, she would need to speak to Thripple. She wanted her advice about a sewing project she had in mind. Sooner or later there would be a coronation, and Fir couldn’t possibly crown Crispin wearing that shabby old tunic.

And what about Gleaner? She felt extremely curious about Gleaner, and more than a little anxious. She had to protect the king, and Gleaner could be dangerous.

FTER THE NIGHT OF THE FAILED RESCUE

FTER THE NIGHT OF THE FAILED RESCUE

, Urchin’s spirits lifted. Juniper recovered slowly. His voice was still no more than a croak and his pointy face looked hollow, but he was awake, conscious, and able to eat and walk. Each day he became a little stronger, making a patch of gladness in the long, frustrating days. They talked of Mistmantle, of the waterfall, and Anemone Wood. They carved pictures on firewood, flipped plum stones into an upturned bowl from as far a distance as possible in a small cell, and made plans for escape, all of which were impossible. And they played endless games of First Five, a Mistmantle game to do with getting five pebbles into a pattern in the middle of a grid while preventing your partner from doing the same. (Cedar provided the pebbles.) The king, who was making a tour of the mine workings and silversmiths, had not sent for Urchin again.

“His Majesty doesn’t want to see you, Freak,” said Bronze, grinning as he brought bread and water. “Not bothered about feeding you very much, either, by the look of things.” The bread and water wasn’t much between two of them, but at least they were left alone, and Cedar smuggled food to them on the rare occasions when she saw them. The hardest thing was knowing that summer was over, autumn was blowing in, and they were still held in a small cell smelling of lice lotion with nothing to explore, nothing changing, and nothing to climb but the walls.

“We should be bringing in the hazelnut harvest,” said Urchin restlessly.

“I hope Damson’s all right,” said Juniper. “She’ll be making cordials from the rose hips, and it’s hard work. I should be there to help her.”

When the king finally did send for Urchin, his mood had changed again. Summoned to the High Chamber, Urchin saw a small hedgehog curled smugly by the king’s throne. He knew he recognized that hedgehog from somewhere, but it took a minute to remember that this was the one who had appeared on the night when the Mistmantle moles had attacked. He was small, but his face was adult and cunning. The king was speaking to him as Smokewreath huddled in a corner, his arms folded and a scowl on his face.

“You’ve done ever so well, Creeper,” the king was saying to the hedgehog. “For now, I think you should just enjoy the fun.” He looked at Urchin, stood up, and held out his paws with a frightening smile. “Dear little Freak, you’re going to come with me around the island. Let me show it off to you? Won’t that be lovely?”

“Yes, Your Majesty!” said Urchin, and his ears twitched with anticipation. At the thought of fresh air he wanted to leap from the nearest window and race the wind.

“Yes, it’ll be such fun!” gushed the king. “And you can tell me where all that lovely, lovely silver is hiding!”

Oh, thought Urchin, and hoped he could bluff his way through convincingly. The king swept toward him and placed both silvered paws on his shoulders.

“Smokewreath’s such a crosspatch today,” he said. “He’s jealous because you might be better at finding silver than he is.” He called over his shoulder to Smokewreath. “I’ve arranged a lovely little killing for you!”

He clapped his paws twice, sharply, and four nervous squirrels shuffled into the chamber carrying something in a blanket. They laid it before the king, and stood meekly back, their paws behind their backs and their heads bowed. Smokewreath edged forward.

Urchin didn’t want to look, but he had to know the worst. He forced himself to look down at what lay in the blanket.

For one horrible moment, he thought it was Cedar. When he gathered himself together he realized it was nothing like her, but it was still the body of a young squirrel with an arrow wound staining her fur. It was a young life, somebody’s daughter, somebody’s friend, who would never go back to her nest.

With a clatter of bones and a stale smell of smoke, sweat, and vinegar, Smokewreath bent over the body. His gnarled front paws clutched at the dead squirrel’s ears and heaved her up, sniffing her face, forcing her mouth open to squint at her teeth, tugging at her fur. Urchin turned his face away in disgust and pressed down the churning in his stomach.

“What’s the matter with you?” demanded the king.

Urchin’s paws tightened. He had to hold himself back from seizing Smokewreath and wrenching him away from the body.

“Don’t you mind that she was killed?” he asked. “She was one of your islanders!”

“As you say,” answered the king. “She was one of my islanders. Mine. Mine to dispose of. Mine, mine, silver mines!” He laughed hysterically and threw an arm around Urchin. “She had to die one day, didn’t she? Oh,” he went on as Urchin flinched from his touch, “are we cold? Lord Marshal, fetch a warm garment for our honored guest!”

“Bronze, get a cloak for the freak,” grunted Granite. Urchin didn’t want one, but he couldn’t afford to annoy the king. He fastened it at his throat as, surrounded by guards and attendants, he followed the king from the palace. It was reassuring to see Cedar take her place among the guards.

His prison was at the opposite side of the Fortress, so he stepped out into part of the landscape he hadn’t seen since he’d first arrived. Gladly he took a deep breath of cool air, but it tasted of dust and made him cough. The leaves had started to twirl down, but like everything else on the island, they lay under the fine gray powder of dust from the mines. As they marched from the Fortress and passed scrawny woodland, he saw that even the fruit and nuts on the trees shimmered with it. Still, after all this time in prison it was wonderful to be outside at all. The king was watching him with a smile of pride.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” he said. “My lovely island! And there’s something you simply must see.”

He led them far away from the Fortress and along a steep path that wound up a hillside, and the farther they walked, the cleaner and kinder the air became, with a sniff of the sea in it. The fallen leaves were deeper here. If he hadn’t been with the king, Urchin would have leaped into them and rolled. As it was, he reminded himself to be alert, his ears twitching, his eyes wide with attention, looking for anything at all that would help when the time came for escape. He needed to find places that would provide cover after leaf fall. The trees grew more thickly here, and there were times when he was very tempted to make a dash for it, but it was far too risky. The archers were proud of their skill, and they’d be glad to show it off. He did his best to take in everything he saw in the hope that he’d remember it, but it wasn’t easy with the king distracting him, throwing an arm around his shoulder or slapping him on the back, and saying, “What do you think? What do you think? Have you smelled silver? Can you feel it? Do you want to stop and have a little search? You do have the gift for finding it, don’t you? Commander Cedar says you have, don’t you, Cedar?”

“Your Majesty,” said Urchin, “do you really think silver is what your island needs? Animals can’t eat it. The dust from the mines is in the soil, it’s everywhere. I think that’s why the trees don’t thrive.”

“Aren’t they healthy trees?” asked the king in alarm. “Don’t you think so? We need trees! We refine the silver in furnaces, and we need trees for the fuel! And coal, of course. We have mines for that, too.”

“More

mining!” said Urchin. “Your Majesty, you don’t

need

silver! You need good, soft earth where things can grow, and healthy plants to grow in it!” The king was gazing into the distance and might not be hearing a single word, but Urchin went on, quickly thinking of all the things hedgehogs like to eat. “Your Majesty, if your soil is good it’ll be full of slugs and worms and beetles, and you can grow berry bushes….”

“Good soil,” murmured the king. “Good earth, with fresh green grass and moss, slugs, and beetles…”

“Yes, that’s what you need.…” urged Urchin.

“…fruit and flowers…”

“Yes!” said Urchin.

“Mmm,” said the king thoughtfully. But Urchin, looking up at his face, saw a gleam of greed and menace that made him shudder from ears to tail tip.

“Nice,” said the king softly. He was almost purring. “Yes, I think so. Yes, I have thought of it. Yes, I want an island like that!”

Urchin didn’t want to guess at what the king meant, but he had a horrible suspicion.

I

want an island like that

…It was a good thing Mistmantle couldn’t be invaded. Then the king flung an arm about him with a force that knocked him paws first into a puddle.

“Come on!” he cried. “Up the hill! It gets harder after this!”

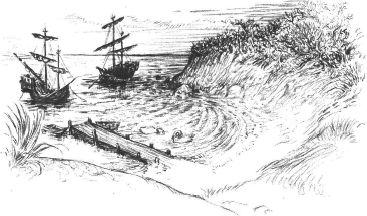

Urchin allowed the king to do the talking as they marched and climbed up the long, steep hillside. Long before they reached the top, he had noticed how much fresher and saltier the breeze had become. A gull wheeled overhead, a far-off swishing of waves reached him; there was sand mixed with the earth—it took all his self-control to keep from dashing ahead over the thick, shrubby bushes and bounding down to the sea. Forcing himself to stay at the king’s pace, he trudged to the top of the dunes, and there he stood and gasped, forgetting all about captivity, feeling a leap of joy in his heart.