Upon the Altar of the Nation (72 page)

Read Upon the Altar of the Nation Online

Authors: Harry S. Stout

To be sure, Sherman never issued direct orders to destroy and plunder private property, let alone to rape “liberated” slaves. But any efforts at restraint were ineffectual; in any case, it was well known that if Sherman expected excesses anywhere it was in Columbia. That expectation amounted to de facto permission in the minds of many. For that, Sherman must take the moral responsibility.

When faced with the ravages of Sherman’s army, Confederate women did not evidence the demoralization that Sherman assumed would ensue. Instead, as with soldiers in the field, after the initial shock their hatreds and determination to fight on were renewed by the violence. Women on farms and refugees in cities may have urged their husbands to desert the war and come home. But women experiencing violence directly urged their soldier husbands to remain in the army and repay the Yankees for their outrages, an eye for an eye.

15

15

To their credit, not all Union soldiers were so destructive, and some tried valiantly to put out the fires. But most of the more humane soldiers remained in the camp outside of Columbia, leaving the city to the hounds of prey. Throughout, the bands played on and the soldiers complimented themselves on a “good time” had by all. When, near midnight, Sherman walked out into the yard of his “headquarters” to view the city skyline bright with flames, he commented simply, “They have brought it on themselves.”

The next morning, as Sherman explored the full extent of destruction wrought by his soldiers, he blamed the mayor for not destroying the liquor. Liquor, and not Union soldiers or their officers, was responsible for the destruction. Left unsaid was why ungoverned soldiers had to be in the city in the first place, when the Confederate “army” of eight hundred was long gone to the northeast. Months after the destruction, William Simms asked the same questions:

If it could be shown that the whiskey found its way out of stores and cellars, grappled with the soldiers and poured itself down their throats, then they are relieved of [moral] responsibility.... But why did the soldiers prevent the firemen from extinguishing the fire as they strove to do? Why did they cut the hose as soon as it was brought into the streets.... Why did they suffer the men to break into the stores and drink the liquor wherever it was found? And what shall we say to the universal plundering, which was a part of the object attained through the means of fire?

16

16

In his memoirs, Grant insisted that Confederate soldiers or citizens probably torched Columbia. No doubt there was carelessness on the part of Confederate soldiers bent on destroying the cotton. And alcohol was available for plunder. Add high winds, and all the ingredients for self-exoneration to the smoldering city are there. But the evident satisfaction that Union soldiers took in the destruction and the failure of Union officers to adequately police their own men surely added to the tragedy.

Remarkably, neither Grant nor Sherman made any moral commentary except to say, in effect, “You deserved it,” no matter what the level of destruction. In a telling concession, Grant argued that even if Sherman’s troops had started the fires or been deliberately delinquent in failing to put them out, they were justified in so doing. In other words, their actions would require no moral defense: “The example set by the Confederates in burning the village of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a town which was not garrisoned, would seem to make a defence of the act of firing the seat of government of the State most responsible for the conflict then raging, not imperative.”

17

In this war, two moral wrongs apparently made one moral right. Sherman agreed: “Though I never ordered [the destruction] and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the war.”

17

In this war, two moral wrongs apparently made one moral right. Sherman agreed: “Though I never ordered [the destruction] and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the war.”

Like Atlanta, Columbia was effectively “not garrisoned,” but the people got what they deserved anyway. It was guilt by geographical association with South Carolina, the state that started the rolling secession of the South. The moral guilt lay not with the Federal soldiers, no matter what they did, but with the people of the South—in particular those of South Carolina. For Sherman, the Confederacy’s Original Sin of secession meant that the entire population deserved wrath and damnation:

I know that in the beginning, I too, had the old West Point notion that pillage was a capital crime, and punished it by shooting.... This was a one sided game of war, and many of us ... ceased to quarrel with our men about such minor things, and went in to subdue the enemy, leaving minor depredations to be charged up to the account of the rebels who had forced us into the war, and who deserved all they got and more.

18

18

Few soldiers expressed reservations over the legitimate “foraging” of South Carolina houses for necessary supplies, and most distanced themselves from pillaging for “trophies,” which was widespread but always relegated to a few rotten apples. Despite explicit prohibitions in Lieber’s Code, the pillaging was systemic, at least in South Carolina, though few owned up to it. Lieber’s Code and Sherman’s orders may have countenanced civilian punishment and exploitation, but many sensed something new and unprecedented was taking place in South Carolina—maybe even something immoral. The historian Jacqueline Glass Campbell recognizes how “the struggle of essentially moral men to come to terms with the violence and terror they were bringing into southern homes suggests that although Sherman’s strategy may have had historical precedent in military terms, in ideological terms, it was understood differently”

19

19

Even as Columbia burned, Charleston surrendered to General Alexander Schimmelfenning after a bracing bombardment. That left Lee effectively isolated. Northern headlines rejoiced in the capture: “Charleston Evacuated! A Bloodless Victory! Charleston is Ours, God and the right are vindicated.”

20

Others praised the cause: “Never since this horrible war began, have we felt more like pouring out our hearts in thanksgiving to God, for any tidings, than for those which we are permitted to announce to-day. Charleston—the birthplace of treason ... is at length in our hands, and the flag of the Union, once more floats over the stronghold of rebellion.“

21

20

Others praised the cause: “Never since this horrible war began, have we felt more like pouring out our hearts in thanksgiving to God, for any tidings, than for those which we are permitted to announce to-day. Charleston—the birthplace of treason ... is at length in our hands, and the flag of the Union, once more floats over the stronghold of rebellion.“

21

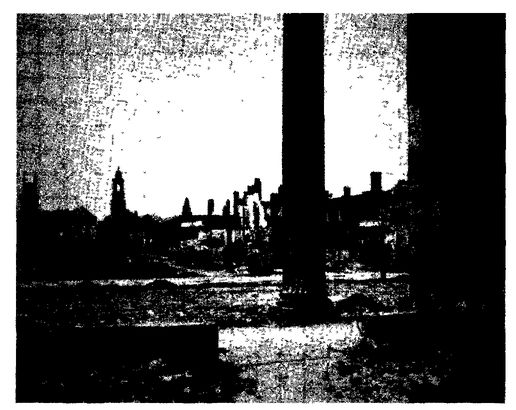

“The Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina,” as seen from the Circular Church. As the “seedbed of rebellion,” no target assumed greater significance for Federal troops than Charleston. After months of bombardment the city was left in ruins and would not be repaired until after the war.

In none of these accounts was Columbia or the destruction to the city mentioned. Nor was destruction to Charleston mentioned at the time. After the war, a report in a Northern paper revealed the devastation wrought by constant bombardments in the “bloodless victory”:

It would be impossible to give even a faint idea of the dreadful effects of this war upon the religious interests of the South. Churches have been shattered and burned, congregations dispersed, benevolent organizations disbanded, Theological Seminaries closed, while many of the clergy wander around without a flock, without a home—some, I fear, without any support except that which may be afforded by the hand of charity.

22

22

Again, Union commanders evidenced no remorse over civilian casualties. General Halleck, like Sherman, was an early believer in the West Point Code, and, like Sherman, he got over it. In a communique to Sherman, he wrote: “Should you capture Charleston, I hope that by some accident the place may be destroyed, and if a little salt should be sown upon its site it may prevent the growth of future crops of nullification and secession.”

23

23

Not all delighted in the devastation. At last the bloodlust seemed to wane as victory loomed imminent. Henry Ward Beecher accepted a Federal invitation to deliver a celebratory sermon to consecrate the redeemed city of Charleston. A writer for the

Philadelphia Inquirer

was surprised to discover Beecher’s intended theme. According to the account, Beecher informed his congregation of his intent to “appeal for universal unity among the people of both sections,” and “now, when it is near its end, his heart yearns for reconciliation with his brethren.” As for Columbia: “Along the seaboard we can give essential relief, but all along the route of Sherman’s army the description given by the prophet is eminently applicable: ‘Before him was the garden of Eden, and behind him was the desert.’ ” In terms of his own intentions for Charleston, “I would be no man’s servant to be the man to go down among them, and when they are burying their dead to taunt them.”

24

Philadelphia Inquirer

was surprised to discover Beecher’s intended theme. According to the account, Beecher informed his congregation of his intent to “appeal for universal unity among the people of both sections,” and “now, when it is near its end, his heart yearns for reconciliation with his brethren.” As for Columbia: “Along the seaboard we can give essential relief, but all along the route of Sherman’s army the description given by the prophet is eminently applicable: ‘Before him was the garden of Eden, and behind him was the desert.’ ” In terms of his own intentions for Charleston, “I would be no man’s servant to be the man to go down among them, and when they are burying their dead to taunt them.”

24

PART VIII RECONCILIATION

MAKING AN END TO BUILD A FUTURE

CHAPTER 43

“LET US STRIVE ON TO FINISH THE WORK WE ARE IN”

I

nauguration Day, March 4, 1865, did not begin well. For several days, Washington had been deluged with rain, and the expectant crowd was soon drenched. Worse was yet to come, for first on the agenda was the inauguration of Andrew Johnson as vice president. Suffering the aftereffects of a bout with typhoid fever, Johnson asked for some whiskey to calm his nerves and proceeded to get rip-roaring drunk. After a rambling speech that Lincoln and his administration could barely endure, he was shown to his seat. A mortified Lincoln leaned over to the parade marshal and instructed him: “Do not let Johnson speak outside.”

nauguration Day, March 4, 1865, did not begin well. For several days, Washington had been deluged with rain, and the expectant crowd was soon drenched. Worse was yet to come, for first on the agenda was the inauguration of Andrew Johnson as vice president. Suffering the aftereffects of a bout with typhoid fever, Johnson asked for some whiskey to calm his nerves and proceeded to get rip-roaring drunk. After a rambling speech that Lincoln and his administration could barely endure, he was shown to his seat. A mortified Lincoln leaned over to the parade marshal and instructed him: “Do not let Johnson speak outside.”

Then came Lincoln’s turn. The applause was ecstatic—the applause of winners. Flags appeared everywhere. Everyone in attendance knew that the defeat of the Confederacy was assured and the time for celebration at hand. In fact, it was a time to gloat. Beyond gloating, the crowd looked forward to words of revenge to punish the demonic South for all the pain and suffering it had imposed on a righteous Union.

The audience would be surprised. Lincoln would offer no lengthy denunciations of the enemy. He would offer no length at all on any theme. In a mere 703 words Lincoln brought together the mystical and fatalistic themes that would later render his speech America’s Sermon on the Mount. The address consisted of a series of propositions in response to the unasked questions that were lodged in the back of every Northern American’s mind. More meditation than pep talk, the speech led ultimately to a unique jeremiad, unlike any heard in the pulpits, newspapers, or arts. Throughout, Lincoln assumed no personal glory in the effort, but instead spoke in the third person.

How

was the war going? Lincoln began with the most important question. Elections, political campaigns, the prospect of reconstruction were all secondary to the great all-encompassing question of war. Happily the signs were good. “The progress of our arms ... is as well known to the public as to myself.” Did this mean that victory was so certain that no further cause for concern existed? Not really. “With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” So much for the celebration.

was the war going? Lincoln began with the most important question. Elections, political campaigns, the prospect of reconstruction were all secondary to the great all-encompassing question of war. Happily the signs were good. “The progress of our arms ... is as well known to the public as to myself.” Did this mean that victory was so certain that no further cause for concern existed? Not really. “With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” So much for the celebration.

Who

caused the war? The North surely had its faults, to which he would return later. But causing the war was not one of them: “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would

make

war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would

accept

war rather than let it perish.” The resulting collision was inevitable: “And the war came.”

caused the war? The North surely had its faults, to which he would return later. But causing the war was not one of them: “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would

make

war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would

accept

war rather than let it perish.” The resulting collision was inevitable: “And the war came.”

Why

would the South make war on the Union? To protect and extend slavery: “All knew this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.”

would the South make war on the Union? To protect and extend slavery: “All knew this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.”

So far so good. Now that good had been separated from evil, it would be time to ask how to punish the miscreants. But again Lincoln headed in an unexpected direction. How could like-minded Christians come to such violently opposed answers to slavery and Union? Both, after all, “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God.” Each “invokes His aid against the other.” Yes, the audience nodded, but we know whose side God was really on. Wrong. Strange as it seemed to own slaves and call it charity, as Southern moralists did to the bitter end, “let us judge not that we be not judged.” What? Judgment, as any Northern minister could have told his congregation, was precisely what God required of his obedient servants.

Other books

SuperZero by Jane De Suza

Too Darn Hot by Sandra Scoppettone

Neither Wolf nor Dog by Kent Nerburn

Earthly Vows by Patricia Hickman

The Underground by Ilana Katz Katz

The Red Collection by Portia Da Costa

Secret Agent Father by Laura Scott

The Devil's Elixir by Raymond Khoury

Red Midnight by Ben Mikaelsen

Lover Reborn by J. R. Ward