Upon a Dark Night (13 page)

Authors: Peter Lovesey

Having toured the field, he approached the house, which was open. The SOCOs had long since collected all the forensic evidence they wanted, and now it was in use as a base for the police. Some attempt had been made that afternoon to get a fire going in the range. He used the bellows on the feebly smouldering wood and soon had a flame, though he doubted if it would give much heat to the kettle on top. The range stood in what must once have been the open hearth, and the section where they had started the fire was intended for coal, but he didn’t fancy exploring the outhouses in search of some.

Here, as the fading afternoon gave increasing emphasis to the flickering fire, he felt a strong sense of the old man shuffling around the brown matting that covered most of the flagstones, seeing out his days here, cooking on the range, dozing in the chair and occasionally stepping outside to collect eggs from the hen-house, or to wring a chicken’s neck. His bed was against the wall, the bedding amounting to a pair of blankets and an overcoat. Thanks to the work of the SOCOs, the place was very likely cleaner at this minute than it had been in years.

The chair - presumably the one the body had been found in - stood in a corner, a Victorian easy chair with a padded seat, back and wooden armrests. He saw the chalkmarks on the floor indicating the position it had been found in. There, also, were the outlines of the dead man’s footprints and of a gun.

A shotgun is not the most convenient weapon for a suicide, but every farmer owns one and so do many others in the country, so the choice is not uncommon. Methods of firing the fatal shot vary. Gladstone’s way, seated in the chair, presumably with the butt of the gun propped on the floor between the knees, and the muzzle tucked under the chin, was as efficient as any. With the arms fully extended along the barrel, both thumbs could be used to press down on the trigger. The result must have been quick for the victim, if messy for those who came after. Diamond looked up and noticed on the ceiling a number of dark marks ringed with chalk. He recalled the rookie constables in their face masks assisting the police surgeon and was thankful that his ‘blooding’ as a young officer had not been quite so gruesome.

For distraction, he crossed the room to a chest of drawers and opened the top one. An immediate bond of sympathy was formed with the farmer, for the inside was a mess, as much of a dog’s breakfast as Diamond’s own top drawer at home. This one contained a variety of kitchen implements, together with pencils, glue, a watch with a broken face, matches, a pipe, a black tie, some coins, a number of shotgun cartridges and thirty-five pounds in notes. The presence of the money was interesting. This drawer, surely, was an obvious place any intruder would have searched for spare cash. The fact that it had not been taken rather undermined his theory that the digging outside had been in search of Gladstone’s savings, unless the digger had been too squeamish to enter the cottage and pick up what had been there for the taking.

The lower drawers contained only clothes, so old and malodorous that the sympathy was put under some strain. He closed the drawer, blew his nose, and looked into the cottage’s only other room, a musty place that could not have been used for years. It was filled with such junk as a hip-bath, a clothes-horse, a shelf of books along a window-ledge, a wardrobe, a roll of carpet, a fire-bucket and other bits and pieces surplus to everyday requirements.

Diamond sidled between the hip-bath and a bentwood hat-stand to get a closer look at the books, all of which had suffered water-damage from a crack in the window behind them. They told him little about the man. There was a county history of Somerset and two others on Somerset villages; an

Enquire Within Upon Everything,

several manuals on farming; one on poultry-keeping; and a Bible.

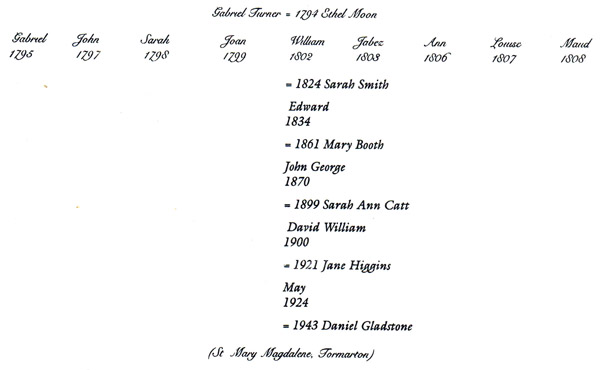

When he picked the Bible off the shelf, the cloth cover flapped away from the board where the damp had penetrated. A pity, because it was clearly an antique. In the end-paper at the front was inscribed a family tree. It went back to 1794, when one Gabriel Turner had married Ethel Moon. Gabriel and Ethel’s progeny of nine spread across the width of two sheets and would surely have defeated the exercise if a later architect of the tree had not decided to restrict further entries to one line of descent, ending in 1943, when May Turner married Daniel Gladstone in St Mary Magdalene Church, Tormarton.

So far as Diamond could discern from the handwriting and the ink, all the entries had been made by two individuals. It appeared that the originals had been inscribed early in the nineteenth century, with the object of listing Gabriel and Ethel’s family; and the later entry was post-1943, to provide a record of May’s link through the generations with her great-great-grandparents. Daniel, presumably, was the suicide victim.

Sad. Now the old farmer would probably be buried in the church where he and his bride had married over half a century ago. Even more touching, the Bible also contained a Christmas card, faded with age, and inside it was a square black and white photo of a woman with a small girl. A message had been inscribed in the card:

I thought you would like this picture of your family. God’s blessing to us all at this time. Meg.

Odd. He turned back the pages to check. The writing was clear. Daniel Gladstone had married May Turner, not Meg.

A second marriage? If so, the message seemed to suggest that it was a marriage under strain.

Hearing someone enter the cottage, he replaced the Bible and its contents where he had found it. John Wigfull heard him and looked through the door, his hair and moustache glistening from exposure to the mist.

‘Digging around?’

‘I thought that was the order of the day,’ Diamond answered.

‘We’ve given up. It’s too dark to see a damned thing and the mist is coming down.’

‘You’re right. I was getting eye-strain looking at his books,’ said Diamond. ‘Not much of a reader, apparently. What an existence. No papers, no telly. I’m not surprised he decided to end it. Did you find any personal papers?’

‘There was a deed-box. I’ve got it at Manvers Street. Birth certificate and so on. It establishes clearly who he was. We can’t trace a next of kin, so a health visitor will have to do the formal identification for us. At least Social Services were aware of his existence. Not many round here were.’

‘You’ve talked to neighbours, then?’

‘They scarcely ever saw him. There was some friction. I think the fellow on the next farm made several offers to buy him out when he stopped working the land, but he was a cussed old character.’

‘Aren’t we all, John?’

Wigfull was reluctant to bracket himself with the farmer or his rival. ‘What I was going to say is that no one could stand him for long. He married twice and both women divorced him.’

‘Any children?’

‘If there were, they didn’t visit their old dad.’

Diamond explained why he asked the question. He picked the Bible off the shelf again and showed the Christmas card and photo to Wigfull.

There wasn’t much gratitude. ‘Could be anyone, couldn’t it? There’s nothing to prove these people were his family. I mean, the Bible looks as if it belonged to the wife. It’s her family tree in the front, not his.’

Diamond didn’t pursue it. Wigfull was discouraged by the digging and even more discouraged by Diamond’s visit.

‘So will you come back tomorrow?’

‘No chance,’ answered Wigfull. ‘I’ve got to get the body identified before we can fix a post-mortem. These lonely people who kill themselves without even leaving a note are a pest to deal with. For the present, I’ve seen more than enough of this God-forsaken place and I’m chilled to the bone. I might send a bunch of cadets out to turn over the other trenches. I don’t expect to find anything.’

‘Any theories?’

‘About the digging? No. If we’d turned up something, I might be interested.’

‘There must be some explanation, John. It represents a lot of hard work.’

‘You think I don’t know? Anyway, I’m leaving. If you want to stay, be my guest. There are candles in the kitchen.’

Doreen had a taxi waiting outside Harmer House. She opened the rear door for Rose, helped her in with the two carrier bags containing all her things, and got in beside her.

The driver turned to Doreen and asked, ‘All right, my love? All aboard and ready to roll?’

Visitors to the West Country are sometimes surprised by the endearments lavished on them. Doreen answered with a nod.

Rose was looking back at the hostel. She felt no regret at leaving the place, only at being parted from Ada, who had been a staunch friend. She was sure Ada would not let the parting get her down, and neither would she, if she could help it.

‘At least you’ll have a room to yourself tonight,’ Doreen said, trying to be supportive.

‘Will I?’

‘It’s like a furnished flat. Your own bathroom, kitchen, everything. I’ve done some shopping for you. Hope you don’t mind pre-cooked meals.’

‘I’ll eat anything, but I don’t have much cash to pay for it.’

‘Forget it, darling. We’re family.’

They drove past the fire station at the top of Bathwick Street and over Cleveland Bridge.

‘Did you walk along here while you were staying at the hostel?’

‘No. It’s new to me.’

Doreen smiled. ‘Different from Hounslow High Street.’

The joke was lost on Rose. The street they had just joined, with its tall, terraced blocks with classical features, might as well have been Hounslow for all she knew.

The taxi moved across the city at a good rate into some more modern areas built of imitation stone that looked shoddy after the places they had left. But presently they drove up a narrow street into a fine, eighteenth-century square built on a slope around a stretch of garden with well-established trees.

‘Your temporary home.’

‘Aren’t you staying here as well?’

‘Just around the corner in a bed and breakfast. You don’t mind having the place to yourself?’

Truth to tell, Rose preferred it. She was drained by the effort of accepting as her sister this woman she had no recollection of meeting before. They got out at the lower end of the square. Doreen had a hefty fare to settle: she counted out six five-pound notes and got a receipt, which she pocketed. Then she escorted Rose to the door. ‘There are shops along there, in St James’s Street, newsagent and grocer combined, deli, launderette, enough for all immediate needs,’ she said, sounding like a travel guide. ‘Oh, and a hairdresser’s.’

‘Does it look that awful?’

‘Of course it doesn’t, but if you’re like me, you get a lift from having your hair done. If not, there’s the pub.’

From the arrangement of doorbells, Rose noted that the house was divided into flats with a shared entrance.

‘Hope you won’t mind the basement,’ Doreen said apologetically, when she had let them in. ‘That’s all I could get at short notice.’

They stood in a clean, roomy and impersonal hall without furniture except a table for the mail.

‘You must have been confident of finding me to have fixed this up.’

‘More than confident, my dear. I knew. Saw your picture in the paper, you see. It said you were being looked after by the Social Services, so it was just a matter of establishing who I was.’

‘And who I am.’

‘Well, yes.’ Doreen led the way downstairs and turned the key in the door. They stepped inside a large room that must have faced onto the square. All you could see through the window was the outer wall of the basement well and, high up, a strip of the street with railings.

‘The living room. Better than the hostel?’

‘I don’t think the hostel had a living room.’

Affectionately Doreen put her arm around her. ‘So this will do?’

‘Home from home.’

In reality, it was just another strange setting for Rose to get used to. She was impatient to get back to her own place, whatever that turned out to be. She hated being under an obligation to people. Unfortunately, there was nothing she could do while Doreen and her partner Jerry chose to linger in Bath.

Fitted green carpet, two armchairs, glass-topped table, bookshelf with a few paperbacks: it would do. The only thing she disliked was having to keep the light on during daytime, a fact of basement life.

‘I’m going to make us a cuppa,’ said Doreen, crossing to the kitchen.

Rose looked into the bedroom. Clean, if rather spartan. Two divan beds with the mattresses showing. A sleeping bag had been arranged on the nearer one. Fair enough, she thought. I could hardly expect them to go to the trouble of buying a full set of bed linen. She put her carrier bags on the spare bed. Unpacking wouldn’t take long.

Back in the kitchen, Doreen showed her the food shopping she had done. There was enough for a couple of days at least. ‘Didn’t know whether you’d gone back to your vegetarian phase, so it’s rather heavy on veggies,’ she said.

‘If I have, it’s all gone by the board in the last few days. I simply don’t remember if I’m supposed to be a vegetarian.’

‘You were always taking up new diets. I could never keep track of them.’ Doreen poured hot water into the teapot and swirled it around. ‘But you like your tea made properly. The pot has to be warmed.’