Under a Wild Sky (31 page)

Authors: William Souder

The elegance of Wilson's raptors showed how far he had come as an artist. This is the Mississippi kite that was copied by either Audubon or his engraver and appropriated for

The Birds of America

. (Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina)

Napoleon's nephew, Charles-Lucien Bonaparte. One of the leading naturalists of his day, Bonaparte “discovered” Audubon, but their long-running relationship was rocky. (

Charles-Lucien Bonaparte as a Young Man

by Charles de Châtillon. Pencil drawing. Used by permission of the Museo Napoleonico, Rome)

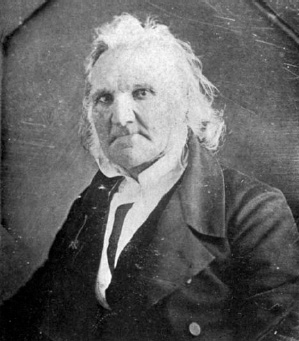

George Ord, whose campaign against Audubon in Philadelphia grew into an obsessive hatred of the ornithologist. (

Portrait of George Ord

by J. Henry Smith, after John Neagle's portrait of 1829. Used by permission of the American Philosophical Society)

Audubon was forty-eight and at the halfway point of his “great work” when Henry Inman painted this portrait in 1833, seven years after

The Birds of America

had begun publication. (Private collection)

The artist Frederick Cruikshank apparently saw a younger Lucy Audubon than the one who posed for this melancholy portrait, circa 1831. Two years earlier she had written to Audubon that she was old and gray and that the last of her teeth were gone. (Collection of the New-York Historical Society)

Audubon's adventures on the American frontierâso unimpressive to the scientific establishment in Philadelphiaâmade him an object of fascination in Britain. He sketched himself in buckskins in this 1826 self-portrait while he was in Liverpool.

Otter Caught in a Trap

. Audubon loved this grisly tableau so much that he painted it over and over again. Not everyone was equally fond of it. (John James Audubon, 1826, oil on canvas. University of Liverpool Art Gallery and Collections)

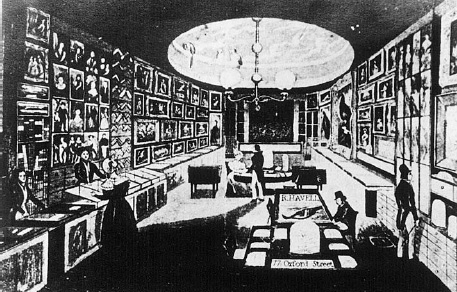

The shop of Robert Havell Jr. on Oxford Street in London, where most of the engravings for

The Birds of America

were made. (Courtesy of the Kentucky Department of Parks, John James Audubon Museum)

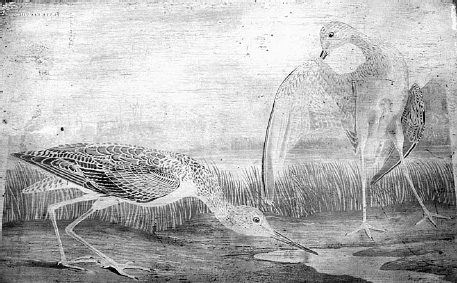

Scratched and blurred but still magnificent, 250 uncolored prints of Audubon's snipe were struck from one of Havell's original copper plates by the Audubon Museum at Henderson, Kentucky, in 2002âmore than a century and a half after it was engraved. Finished prints for

The Birds of America

were completed by teams of painters who hand-colored such black-and-white images. (Photograph of copper plate #308 © C. Wesley Allen. Used by permission of C. W. Allen and John James Audubon Museum, Henderson, Ky.)

John James Audubon, in a rare daguerreotype from 1850, the year before he died.

Difficult as it was to scratch out a living, Audubon managed to send a few dollars to Lucy from time to time. Young Mason, who might have become another worrisome obligation, had meanwhile turned out to be very much the opposite.

He seemed a steadying and cheerful influence on Audubon, who wrote to Lucy that Mason now drew flowers “better than any man, probably, in America.” Audubon believed the boy's skill would serve as an advertisementâproof that Audubon was a superb instructor and mentor to budding artists. He added that the cost of having Mason with him was next to nothing and that the boy's company was “quite indispensable.” As one month followed another in Louisiana, Audubon suffered through one of the unhappiestâand yet one of the most productiveâperiods of his life. He missed Lucy and the boys. He struggled to earn enough money to get by. New Orleans seemed perpetually unkind to him. Audubon's mood was volatile. He worked hard, especially on a drawing of the brown pelican, a bird of which he was particularly fond.

But sour feelings were never far from his mind. “I rose early,” he wrote in his journal in mid-January, “tormented by many disagreeable thoughts, nearly again without a cent, in a Busling City where no one cares a fig for a Man in my situation.” Still eager to join a government-sponsored expedition to the Pacific, he could get no answer to his requests for a position on one as a naturalist and artist. Audubon called on local painters and art instructors, who were mostly dismissive of his talent and who also said he charged too much for his work. An exception was the painter John Vanderlyn, who thought Audubon's birds remarkable. But such bright moments were few. Audubon complained about everything. On the streets he saw people who avoided him and vice versa. Even the weather at times seemed intolerable. The almost perpetual warmth that attracted so many birds was sometimes swept away by a sudden wintry blast, and on a couple of occasions it snowed. Audubon and Mason, confined to cramped, dingy apartments much of the time, lived in a state of perpetual anxiety. Again and again, Audubon confessed bleak thoughts in his journal entries. As he and Mason moved around, they hired a woman to cook and clean for them when they could afford it. More often, they were broke, sometimes living back aboard the keel-boat.