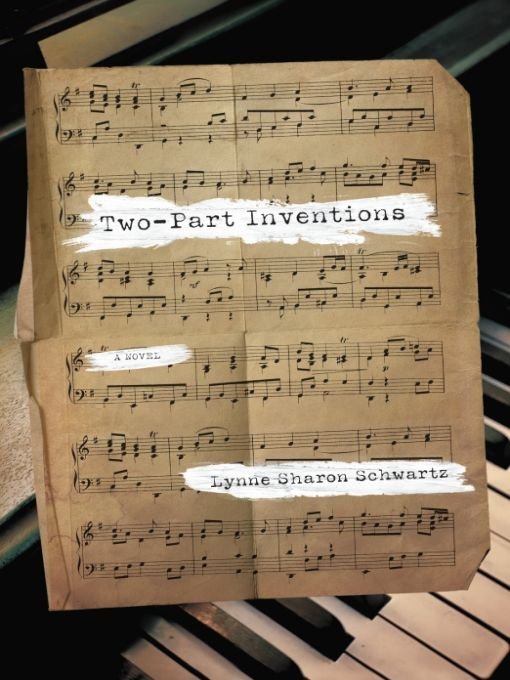

Two-Part Inventions

Read Two-Part Inventions Online

Authors: Lynne Sharon Schwartz

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Overture

Â

T

HE HIGH PIERCING WAIL reached him even before he got to the front door, so jarring that he dropped his keys on the flagstones. The wail sounded like a small creature being tortured, a bird, maybe. A demented form of birdsong. But there was no pause for breath or change in tone, no hint of sputtering life. The shriek kept up at that bizarrely high pitch, the far end of the keyboard, while he fumbled at the door and finally rushed inside, dropping his briefcase and laptop on the shelf in the front hall.

HE HIGH PIERCING WAIL reached him even before he got to the front door, so jarring that he dropped his keys on the flagstones. The wail sounded like a small creature being tortured, a bird, maybe. A demented form of birdsong. But there was no pause for breath or change in tone, no hint of sputtering life. The shriek kept up at that bizarrely high pitch, the far end of the keyboard, while he fumbled at the door and finally rushed inside, dropping his briefcase and laptop on the shelf in the front hall.

Where was she? It couldn't be Suzanne. It wasn't a human sound. He followed it through the living room, past the grand piano with open sheets of musicâBartók, Poulenc, Stravinsky, he registered automaticallyâand into the kitchen, where billows of steam seethed and rose in clumps from the red teapot, already forming cloudy patches on the tiles behind it. He tripped over her body, stretched out flat on the floor, on her back. She looked like a ballerina who falls back in a firm, elegant line, confident that her cavalier will be there to break her fall and propel her on to her next step. But no one had been there to catch her. Before he knelt to see if Suzanne was still breathing, he stepped over her to turn off the flame under the screeching pot.

No breath, no pulse. This couldn't be. It was simply impossible. They had plans.... He had plans. Should he call for help? It was too late. And yet her face and hands were still warm. She couldn't have been lying there long; there was still water in the pot. The empty mug was on the counter, the one she liked, with the picture of Mozart, given to her, half-jokingly, by the director of the Vienna Conservatory when they visited a few years ago. A potholder lay near her on the floor. He stroked her face, as if he could bring her back to life, as if there were a grace period after deathâten minutes, fifteen minutes, and the loved one might return. But that didn't happen.

He had to do something, call someone. But he couldn't, not just yet. How could he even speak? And they would come and take her, and he couldn't let her go yet. His throat tightened with tears but he held them back; he hated to cry. Years ago, as a boy, he had once cried every night for weeks, then stopped abruptly and vowed never again to be so defeated. He held her large limp right hand in his, studying the long pianist's fingers, the carefully trimmed nails, short so as not to click on the keys, then placed it on the floor. If only he had gotten home ten minutes earlier, if only he hadn't made that last phone call from his studio to a new clientâuseless anyway, he'd left a messageâif not for the interminable construction on the Thruway, he might have saved her, at least gotten help. What a cruel offense, he thought, that the last sound she heard was that dreadful screech. She with her musician's ears, her hatred of harsh invasive noises. In their apartment in the city in the early days, before they could afford this house, before together they began producing the CDs that made her reputation, she'd

complained of the car alarms that punctured the dead of night, their maddening repetitive tuneless tunes and whines, as well as the police sirens and fire enginesâthey'd lived around the corner from a firehouse. They go right up my spine, she used to say, they're zapping my brain cells. She was awakened every Wednesday and Saturday at six thirty by the garbage truck under their windowâaudible even over the hum of the air conditioner in summerâthe sound of the heavy bags being tossed into the truck's maw and crunched by its fierce teeth.

complained of the car alarms that punctured the dead of night, their maddening repetitive tuneless tunes and whines, as well as the police sirens and fire enginesâthey'd lived around the corner from a firehouse. They go right up my spine, she used to say, they're zapping my brain cells. She was awakened every Wednesday and Saturday at six thirty by the garbage truck under their windowâaudible even over the hum of the air conditioner in summerâthe sound of the heavy bags being tossed into the truck's maw and crunched by its fierce teeth.

Sensitive ears. Small ears. He used to joke about her ears, so small and delicate. How could they hear so much, he'd ask, running his fingers along the rim. He ran his finger along her ear, still warm, then sat down on the floor beside her. What would he do now? He had made her ambition his life's work. What was left to do?

A

New York Times

was on a kitchen chair. She must have been about to read it while she had her tea. She never read the paper in the morning; it distracted her from practicing, she said. Late in the day, when she was done, she would sit down with the paper or a book before she started dinner. Now, as always, she liked to cook. Years ago, in the dark years of her despair, she had learned to cook elaborate dishesâshe found companionship with Julia Childâsimply to do something with her restless hands, and at last when the despair passed (because he found a way to lure her out of it, Philip liked to think), the habit of cooking remained.

New York Times

was on a kitchen chair. She must have been about to read it while she had her tea. She never read the paper in the morning; it distracted her from practicing, she said. Late in the day, when she was done, she would sit down with the paper or a book before she started dinner. Now, as always, she liked to cook. Years ago, in the dark years of her despair, she had learned to cook elaborate dishesâshe found companionship with Julia Childâsimply to do something with her restless hands, and at last when the despair passed (because he found a way to lure her out of it, Philip liked to think), the habit of cooking remained.

The headline in the paper was about the election fiasco. The Supreme Court had declared George Bush the winner, even though he most likely was not. They'd heard the news together

on the radio that morning, Suzanne wrapped in a towel, just out of the shower, still so beautiful. The perfect skin and willowy shape, with a faint middle-aged droop to her body that he found irresistible. They were both angry and indignant, though only Suzanne was surprised. Philip had predicted the outcome. “How can they do it?” Suzanne asked. “How can they allow such an injustice? It's . . . it's a fraud. Pure fraud. We'll be calling him President but Gore had the votes. Everyone knows that.”

on the radio that morning, Suzanne wrapped in a towel, just out of the shower, still so beautiful. The perfect skin and willowy shape, with a faint middle-aged droop to her body that he found irresistible. They were both angry and indignant, though only Suzanne was surprised. Philip had predicted the outcome. “How can they do it?” Suzanne asked. “How can they allow such an injustice? It's . . . it's a fraud. Pure fraud. We'll be calling him President but Gore had the votes. Everyone knows that.”

“That's the way the world goes, sweetheart,” he said, lacing up his shoes. “You of all people should know that.” Those were almost the last words he'd spoken to her. He'd meant to call during the day, but things were so busy in the studio, a group working on a recording of the Archduke Trio, at it for hours, no break, sandwiches brought in at four, that he hadn't had a chance. Now the words scraped the inside of his skull. That's the way the world goes. You of all people should know that. He hoped those weren't the words she took with her to her death. He hoped she'd forgotten them. He hoped she'd forgotten their last argument, too, over a week ago; the memory was still raw. There had been a few days of coolness, but she couldn't keep it up. Though quiet and wary with new people, at home she was talkative, more and more as she got older. She spent much time alone, and in the evening she liked to tell him every small thing that had happened during the day. She talked most when things were going well; her reserve was saved for times of wretchednessâshe had always been that way, even back in high school, where they had met. After the first few cool days, things were gradually returning to normal. Or so he hoped. She must be getting used to the idea, he thought, the matter

they had argued over, and seen that it was the reasonable next step. Now he'd never know for sure.

they had argued over, and seen that it was the reasonable next step. Now he'd never know for sure.

Â

Â

The following weeks were a vast, gray-skied prairie of grief Philip Markon imagined he might be traversing forever. But in the emptiness of the landscape, broken only by work deadlinesâthere was no letting things go in the recording businessâand by the buzzing of reporters' calls and emails, buzzards picking at the remains, he found a tiny place of shelter, like a prairie dog burrowing into an underground hole. Maybe this premature deathâshe was just fifty, a stroke, the doctors said, which might have left her partially paralyzed had she survived itâwas lucky for Suzanne. She would not have to face the speculationsâmore than speculations, if he was candidâthat had begun on the music websites. The same sites that had raved about her talents, Half-Note, Andante, Platinum

,

now were releasing a flurry of nastiness about her recordings that could grow into a blizzard as the zealots gathered their electronic evidence. Every day the computer programs became more sophisticated, able to compare speeds and pressures and dynamics, identifying performances and passages, printing the data as if they were running a corporation rather than dealing with an ineffable art and volatile artists. The technicians were glued to their consoles, and the critics, armed with the retrieved data, would have plenty to fill their columns and blogs. How they would gloat at destroying a reputation. How stunned their readers would be. No matter that he and Suzanne had worked so hardâ

he

, especially, had worked so hardâto win her the recognition she'd spent years struggling for, that she deserved. She wouldn't have

had the strength to withstand the ugly publicity, the notoriety that was sure to grow. Her strength was in her hands, in her wrists and arms, in her ear. There she possessed might and endurance. Otherwise she was naive, easily bruised, an innocent. He, on the other hand, was prepared for any kind of assault, any crude online chatter. Whatever his business might suffer, he could handle it. He was hard. Nothing could touch him. He was impervious, his defenses constructed in early childhood.

,

now were releasing a flurry of nastiness about her recordings that could grow into a blizzard as the zealots gathered their electronic evidence. Every day the computer programs became more sophisticated, able to compare speeds and pressures and dynamics, identifying performances and passages, printing the data as if they were running a corporation rather than dealing with an ineffable art and volatile artists. The technicians were glued to their consoles, and the critics, armed with the retrieved data, would have plenty to fill their columns and blogs. How they would gloat at destroying a reputation. How stunned their readers would be. No matter that he and Suzanne had worked so hardâ

he

, especially, had worked so hardâto win her the recognition she'd spent years struggling for, that she deserved. She wouldn't have

had the strength to withstand the ugly publicity, the notoriety that was sure to grow. Her strength was in her hands, in her wrists and arms, in her ear. There she possessed might and endurance. Otherwise she was naive, easily bruised, an innocent. He, on the other hand, was prepared for any kind of assault, any crude online chatter. Whatever his business might suffer, he could handle it. He was hard. Nothing could touch him. He was impervious, his defenses constructed in early childhood.

Â

Â

In those weeks after her death the phone rang so often that he was tempted to hurl it against a wall. He let the machine take the calls, and he returned hardly any, except those from close friends or family, certainly not the ones from music bloggers blandly offering condolences and hoping he'd answer just a few questions. He persuaded himself that he was impenetrable, and that was almost true when it came to the rumor-mongers, the pedantic technicians chiming in with their numbers and statistics. None of it mattered now: Suzanne was gone, the CDs were over, there would be no new ones. (Not that he wouldn't release the last, almost finished one, just a little more editing on the final mix.) He saved the messages, though; there might come a time when he'd want to answer them or need them to defend himself. For the time being he had nothing to say; he'd stonewall, and it would all pass. Fortunately, the obituary in the

Times

(“World-Class Pianist Known by Few”) was nothing but admiring and respectful.

Times

(“World-Class Pianist Known by Few”) was nothing but admiring and respectful.

Other books

Bellagrand: A Novel by Simons, Paullina

Take Me There by Carolee Dean

To Love a Scoundrel by Sharon Ihle

Lilith: a novel by Edward Trimnell

Eat Prey Love by Kerrelyn Sparks

Fool's Fate by Robin Hobb

Present at the Future by Ira Flatow

ALM06 Who Killed the Husband? by Hulbert Footner

Alien Mate (Zerconian Warriors Book 3) by Sadie Carter

The One For Me - January Cove Book 1 by Hanna, Rachel