Two Miserable Presidents

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

For Anna, in the hope she'll grow up to be a fellow history fan.

-S.S.

Table of Contents

Title Page

How to Rip a Country Apart

How to Rip a Country Apart

Stop That Cane!

Step 1: Plant Cotton

Step 2: Grow Apart

Step 3: Keep Your Balance

Step 4: Fight Slavery

Step 5: Build a Railroad

Step 6: Get More Land

Step 7: Try to Compromise

Step 8: Chase Fugitives

Step 9: Write Books

Step 10: Divide Nebraska

Step 11: Race to Kansas

Step 12: Insult Senators

Step 13: Hit Him Again!

Step 1: Plant Cotton

Step 2: Grow Apart

Step 3: Keep Your Balance

Step 4: Fight Slavery

Step 5: Build a Railroad

Step 6: Get More Land

Step 7: Try to Compromise

Step 8: Chase Fugitives

Step 9: Write Books

Step 10: Divide Nebraska

Step 11: Race to Kansas

Step 12: Insult Senators

Step 13: Hit Him Again!

This Is Going to Be Serious

Confusion on the Battlefield

Thomas Gets a Nickname

Little Mac Takes Command

Stuck in Washington

Two Soldiers: Frank and Harry

Attack of the Floating Barn

Clash of the Ironclads

From “Useless” Grant â¦

⦠to “Unconditional Surrender” Grant

Time to See the Elephant

The Shiloh Surprise

Into the Hornets' Nest

Lick 'Em Tomorrow

Thomas Gets a Nickname

Little Mac Takes Command

Stuck in Washington

Two Soldiers: Frank and Harry

Attack of the Floating Barn

Clash of the Ironclads

From “Useless” Grant â¦

⦠to “Unconditional Surrender” Grant

Time to See the Elephant

The Shiloh Surprise

Into the Hornets' Nest

Lick 'Em Tomorrow

Two Miserable Presidents

Miserable in Washington, D.C.

Miserable in Richmond

Jackson's Distraction

“La Belle Rebelle”

Whenever You're Ready, George

Seven Days with Granny Lee

What About Slavery?

Robert Smalls's Dash to Freedom

Lincoln Is Convinced

Lee's Hungry Wolves

Who Dropped the Cigars?

Into the Awful Tornado

Mac vs. Lincoln

The Time Has Come

Miserable in Richmond

Jackson's Distraction

“La Belle Rebelle”

Whenever You're Ready, George

Seven Days with Granny Lee

What About Slavery?

Robert Smalls's Dash to Freedom

Lincoln Is Convinced

Lee's Hungry Wolves

Who Dropped the Cigars?

Into the Awful Tornado

Mac vs. Lincoln

The Time Has Come

The Bloody Road to Richmond

Grant's Pretty Simple Plan

Once More into the Wilderness

No Turning Back

Spotsylvania Horrors

June 3: I Was Killed

The Ticking Clock

Waiting for News

“Deader Than Dead”

Some Great Change Takes Place

Election Day, 1864

Why the South Hates Sherman

Lincoln Looks Ahead

Empty Stomachs and Brave Hearts

Waking from the Nightmare

Meeting at Appomattox

600,000 Plus One

Stuck with Each Other

Once More into the Wilderness

No Turning Back

Spotsylvania Horrors

June 3: I Was Killed

The Ticking Clock

Waiting for News

“Deader Than Dead”

Some Great Change Takes Place

Election Day, 1864

Why the South Hates Sherman

Lincoln Looks Ahead

Empty Stomachs and Brave Hearts

Waking from the Nightmare

Meeting at Appomattox

600,000 Plus One

Stuck with Each Other

On May 22, 1856, a congressman from South Carolina walked into the Senate chamber, looking for trouble. With a cane in his hand, Preston Brooks scanned the nearly empty room and spotted the man he wanted: Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. Sumner was sitting at a desk, writing letters, unaware he had a visitor. He became aware a moment later, when he looked up from his papers just in time to see Preston Brooks's metal-tipped cane rising high above his head.

S

o Preston Brooks's metal-tipped cane is about to land on a senator's head. Interesting. But before that cane actually crashes onto Charles Sumner's skull, let's step back and take a look at the events leading up to this moment. Because, believe it or not, if you can figure out why Preston Brooks was so eager to attack Charles Sumner, you'll understand the forces that ripped the United States apart and led to the Civil War.

o Preston Brooks's metal-tipped cane is about to land on a senator's head. Interesting. But before that cane actually crashes onto Charles Sumner's skull, let's step back and take a look at the events leading up to this moment. Because, believe it or not, if you can figure out why Preston Brooks was so eager to attack Charles Sumner, you'll understand the forces that ripped the United States apart and led to the Civil War.

Mr. Brooks, please hold that cane in the air for just a few minutes. We're going to run through a quick thirteen-step guide to tearing a country in two.

A

fter finishing college in 1792, a young man from Massachusetts named Eli Whitney headed south in search of a teaching job. He wasn't too interested in teaching, thoughâhe really wanted to be an inventor.

fter finishing college in 1792, a young man from Massachusetts named Eli Whitney headed south in search of a teaching job. He wasn't too interested in teaching, thoughâhe really wanted to be an inventor.

Whitney got his big chance when he met Catherine Greene, who owned a plantation in Georgia. Greene told Whitney that plantation owners wanted to grow more cotton. The problem was, cotton had to be cleaned by hand and it took forever to pick the sticky green seeds out of the fluffy white cotton. If only there was a way to clean cotton more quickly, planters could grow and sell much more of it.

Greene set up a workshop for Whitney, and he quickly came up with an invention he called the cotton gin (“gin” was short for engine). Whitney proudly announced the benefits of using his machine: “One man will clean ten times as much cotton as he can in any other way before known and also clean it much better.”

Before Whitney's invention, farmers grew cotton only along the Atlantic coast. Now they raced to plant more cotton, forming a wide belt of cotton plantations across the southern United States, from the Atlantic Ocean all the way west to Louisiana and Texas. Plantation owners made huge profits selling their cotton to clothing factories in the northern United States and in Great Britain. Cotton became so valuable to the economy that Southerners declared: “Cotton is King!”

This was great for Southern plantation owners and Northern factory owners. But it was terrible for enslaved African Americans. Planting and picking cotton took huge amounts of work, and that work was done by slaves. So as plantation owners planted more and more cotton, they decided that they needed more and more slaves. The number of people enslaved in the South jumped from just over 1 million in 1820 to about 4 million by 1860.

A

t the same time, the states of the North gradually ended slavery. This was partly because many Northerners thought slavery was wrong. But let's be honest: it was mainly because slavery just didn't make sense in the Northern economy. Most farmers owned small family farms, so they couldn't afford slaves. And factory owners had no interest in owning their workersâthey made more money by hiring workers and paying them a few cents an hour.

t the same time, the states of the North gradually ended slavery. This was partly because many Northerners thought slavery was wrong. But let's be honest: it was mainly because slavery just didn't make sense in the Northern economy. Most farmers owned small family farms, so they couldn't afford slaves. And factory owners had no interest in owning their workersâthey made more money by hiring workers and paying them a few cents an hour.

Slavery was only one of many differences between the North and South in the first half of the 1800s. Most Americans still lived and worked on farms in both the North and South. But life in the North was changing as more and more people moved to cities and took jobs in factories. Immigrants from Europe were also settling in growing northern cities. Northerners were busy building canals and railroads to connect cities and farms. There was less change in the South, where more than ninety percent of the people lived on farms or in small towns. The Southern economy was based on farm products: sugar, rice, tobacco, and especially “king” cotton.

The North and South were developing different ways of lifeâso what? These differences mattered because they made it harder for Northerners and Southerners to agree on plans for the future. For example, take the issue of tariffs, or taxes on imported goods. Sounds pretty boring, right? But tariffs got people excited in those days. Suppose you asked a Northern factory owner and a Southern plantation owner: “Do you support a tariff on manufactured goods imported from Europe?”

“Of course!” the factory owner might say. “Tariffs make imported goods more expensive. So Americans are more likely to buy things made here in our own factories. And that's good for American companies.”

“No way!” the plantation owner might say. “We want to buy the goods we need at the best possible prices. Why should we pay higher prices for manufactured goods just to help make Northern factory owners richer?”

N

ow that the North and South are growing apart, let's look at another issue that's about to cause trouble: land. To put the problem simply: What's going to happen with all that land west of the Mississippi River?

ow that the North and South are growing apart, let's look at another issue that's about to cause trouble: land. To put the problem simply: What's going to happen with all that land west of the Mississippi River?

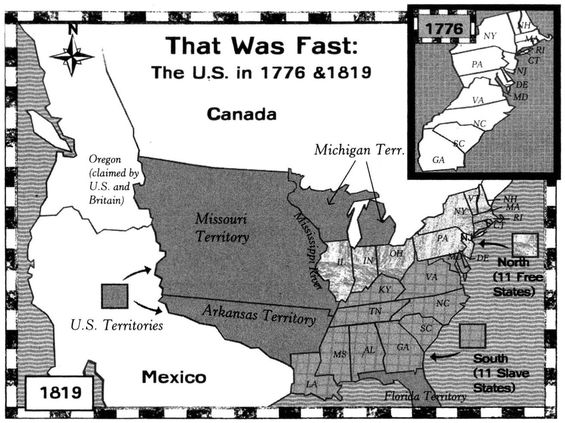

As you probably know, the United States started out as thirteen states along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. But the country had grown quickly:

Why is this new land important to our story?

In 1819 there were a total of twenty-two states: eleven “slave states,” or states with slavery, and eleven “free states,” or states where slavery was illegal. Most members of Congress thought it was a good idea to keep this balance between free and slave states. That way neither North nor South would get too much power in government (or get too angry at the other side).

But everyone knew that western territories would soon be divided up into statesâwould those new states allow slavery? That was the question Northerners and Southerners were beginning to argue about.

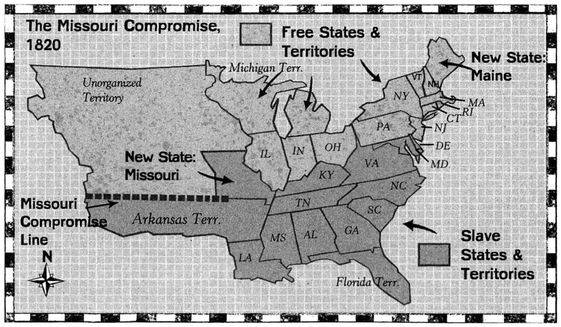

So when Missouri asked to join the Union as a slave state, Congress worked out a deal called the Missouri Compromise. In 1820 Missouri joined the Union as a slave state. And to keep the balance, Maine joined as a free state.

What about all the land west of Missouri? Members of Congress drew a line west from the southern border of Missouri. They agreed that the territory north of the line would someday be divided into free states, and the territory south of the line would be divided into slave states.

The goal was to protect the balance between North and South.

Think it worked?

F

rederick Douglass was not interested in keeping the balance.

rederick Douglass was not interested in keeping the balance.

Born into slavery in Maryland, Douglass grew up working on farmsâand thinking nonstop about slavery. How could one person own another? “Why am I a slave?” he wondered. “I will run away. I will not stand it.”

When Douglass was eighteen, the man who owned him put him to work in a Baltimore shipyard. One day four white workers attacked him with bricks, knocking him down and kicking him in the face over and over. Fifty white men just stood there watching. Douglass's owner (“Master Hugh,” as Frederick called him) went to a judge to complain:

Judge Watson:

Who saw this assault of which you speak?

Who saw this assault of which you speak?

Master Hugh:

It was done, sir, in the presence of a shipyard full of hands.

It was done, sir, in the presence of a shipyard full of hands.

Judge Watson:

Sir, I am sorry, but I cannot move in this matter, except upon the oath of white witnesses.

Sir, I am sorry, but I cannot move in this matter, except upon the oath of white witnesses.

Master Hugh:

But here's the boy; look at his head and face, they show what has been done.

But here's the boy; look at his head and face, they show what has been done.

But Douglass was a slave, a person with no rights. His word meant nothing. The white workers who had seen the beating refused to testify, so the men who had attacked Douglass were never punished.

Douglass continued working (and giving every cent he earned to Master Hugh). And he thought more and more about trying to

escape to the North. He knew the danger. If caught, he could be sold to a cotton plantation far to the south.

escape to the North. He knew the danger. If caught, he could be sold to a cotton plantation far to the south.

He came up with a simple, daring plan. In the South, free African Americans had to carry “free papers”âidentification papers proving they were not slaves. Douglass borrowed these papers from a free friend who was a sailor. Then he dressed in sailor's clothes, put the borrowed papers in his pocket, and boldly walked onto a train. The train started north through Maryland.

There was only one problem: free papers included a description of the person, and Douglass looked nothing like his friend.

Douglass tried to quiet his pounding heart as the conductor came through the black passengers' car inspecting everyone's papers. “This moment of time was one of the most anxious I ever experienced,” he later wrote.

“Had the conductor looked closely at the paper, he could not have failed to discover that it called for a very different looking person from myself, and in that case it would have been his duty to arrest me to Baltimore.”

Frederick Douglass

But the conductor only glanced at the papers, then handed them back to Douglass. The train sped north, and that afternoon Douglass reached the free state of Pennsylvania. He continued on to New York. “I found myself in the big city of NewYork,” he remembered, “a free man.”

Douglass soon found work in a Massachusetts shipyard. And he became an active abolitionistâpart of a movement to end slavery in the United States.

Other books

It All Started With a Lima Bean by Kimi Flores

From Scotland with Love by Katie Fforde

Desperate Measures by Laura Summers

Beautiful Whispers (Ausmor Plantation Book 1 - Romance/Suspense) by Ayden, Alice

Exposed by Alex Kava

Dead Birmingham by Timothy C. Phillips

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert trans Lydia Davis

Spirit by J. P. Hightman

Turning Point by Lisanne Norman

The Good Sinner's Naughty Nun by Fox, Georgia