Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice (56 page)

Read Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice Online

Authors: Naomi Roht-Arriaza

No previous trials of the leaders of authoritarian regimes for human rights violations during their governments had ever been held in Latin America. The Bolivian Congress initiated accountability trials against high‐ranking members of the military government of General Garcia Meza in 1984, but the proceedings did not begin until 1986, and the decisive phase of the trial occurred from 1989 to 1993.

[12]

Globally, if we focus on countries holding their own leaders responsible for past human rights violations, the only precedents to the Argentine trials of the Juntas were successor trials after World War II, and the trials of the Greek colonels in 1974 in Greece. In this sense, just as the Argentine truth commission initiated the cascade of truth commissions, the Argentine trials of the Juntas also initiated the modern cascade of transitional justice trials.

It is quite interesting that Argentina should have been the first in initiating both of the major transitional justice mechanisms explored in this book. It also leads us to question the supposition of early work that framed the debate in terms of “truth”

or

“justice.” When the Argentine military carried out various coup attempts against the

Alfonsín government, it led the government to decree two laws that

were essentially amnesty laws,

Punto Final

and

Obediencia Debida

(Full Stop and Due Obedience laws). This experience was also a formative moment for the transitional justice movement, because it led many to what we characterize as a “misreading” of the Argentine “lesson.” Analysts concluded that human rights trials were not viable, because they would provoke coups and undermine democracy. But this analysis misinterprets the actual sequence of events in Argentina. In Argentina, the nine Junta members were tried and five were convicted. The two most important leaders of the first Junta,

General Videla and Admiral Massera, were sentenced to life in prison. The remaining three were sentenced to between four and a half

and seventeen years in prison.

[13]

The coup attempts did not begin until more far‐reaching trials against junior officers were initiated. So to read the Argentine case as an example that trials in and of themselves are not possible is to disregard the successfully completed trial of the Juntas. The amnesty laws did not reverse or overturn the previous trials, they simply blocked the possibility of more trials. The government of

Carlos Menem that followed the

Alfonsín government then offered a pardon to the convicted military officers in jail. This pardon was again interpreted by some as an indication that the trials had been futile. But pardons did not reverse the trials or the sentences. The Junta members were still (are still) considered guilty of the crimes of which they were accused and for which they were convicted. They had served four years of their prison terms. In the words of some of the most astute observers of the Argentine trials, despite the concessions granted by Alfonsín and

Menem, the “high costs and high risks suffered by the armed forces as a result of the investigations and judicial convictions for human rights violations are central reasons for the military's present subordination to constitutional power.”

[14]

The Argentine case was important for the transitional justice movement in multiple ways. It made early use of many important transitional justice mechanisms, including a truth commission, trials, and reparations. Few countries, however, could have followed easily in Argentina's footsteps and held near‐immediate trials of the top leaders for human rights violations. Argentina's transition was different from the transition in Uruguay, or Chile, or South Africa, for example, and the nature of transition influenced what transitional justice mechanisms were possible, at least in the early transition period.

The transitions literature called our attention to the differences between the so‐called negotiated or “pacted” transitions, where the military negotiate the transition, and ensure significant protections and guarantees for themselves from prosecution for human rights violations, and the “society‐led” transitions, or “rupture transitions” where the military are forced to exit from power without negotiating specific protections.

[15]

Argentina is an example of a society‐led transition after a collapse of the military government in the wake of the failure in the Malvinas War. Chile, Uruguay, and South Africa are classic “pacted” transitions. These differences in transitions help explain why it was more possible for Argentina to hold trials of the Juntas almost immediately following the transition, and why it was more difficult to hold such trials elsewhere. The main previous case of domestic trials prior to the case of Argentina came after a similar type of transition: the Greek trials in 1974 came after the collapse of the Greek authoritarian regime after its failure to effectively confront the Cyprus crisis.

[16]

The case of trials that most closely

followed the Argentine case, that against the military dictator García Meza in Bolivia, also occurred after a society‐led movement that provoked a collapse of the military rule and a “transition through rupture” rather

than a negotiated transition.

[17]

Transitional justice norms and practices have diffused rapidly across the Americas and throughout the world, significantly increasing each decade since

CONADEP and the trials of the Juntas made their public impact both in and beyond Argentina in the early 1980s. This book illustrates many of those trends. In order to illustrate the reach and significance of this global justice cascade, we identified truth commissions and trials for past human rights violations using existing data sets, human rights organization reports, government documents, and information provided by non‐governmental organizations; and analyzed our data in order to ascertain dominant trends.

[18]

Analysis of our data demonstrates a rapid shift toward new norms and practices providing more accountability for human rights violations – a shift that is regionally concentrated yet internationally diffuse. Specifically, our data demonstrates a significant increase in the judicialization of world politics both regionally and internationally, and illustrates a notable variance in the degree of openness of domestic and international institutions over time and across regions. This is the first effort to present quantitative evidence of the justice cascade, which has previously been described only in qualitative case studies and legal analysis. It may be particularly useful to persuade skeptics who continue to believe that the justice cascade is not occurring, or is less substantial than our data suggests.

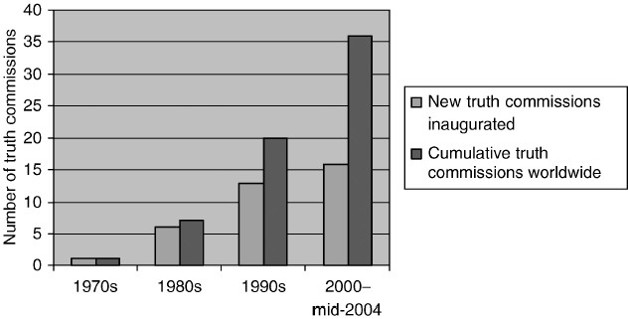

As figure

12.1

illustrates, the number of truth commissions worldwide has increased rapidly over the past two decades with the most dramatic increase occurring between 2000 and mid‐2004. Uganda inaugurated the first truth commission in 1974, followed by Bolivia in 1982; however, neither truth commission produced a final report of their findings. In this sense, we argue that Argentina's truth commission was the first major commission that would have a more lasting impact regionally and globally. Following the inauguration of Argentina's truth commission in 1983, an additional four truth commissions were established before the end of the decade. During the 1990s, thirteen new truth commissions were established and sixteen truth commissions were inaugurated between the years 2000 and mid‐2004, including the first truth commission in the Middle East and North African region (Morocco, 2004). An additional five truth commissions, not included here, were proposed or

under development by June 2004, including those in Bosnia‐Herzegovina, Burundi, Indonesia, Kenya, and Northern Ireland. Thus, we suspect that this significant growth trend will be much steeper by the end of the decade. Already in 2004, the number of truth commissions newly established at the start of the twenty‐first century is only four commissions short of doubling the number of truth commissions inaugurated during the previous decade of the 1990s. In sum, by mid‐2004 a cumulative number of thirty‐five truth commissions had been established worldwide, the first of which had been established thirty years before.

It is important to note that other forms of transitional justice mechanisms that have been established for the primary purpose of establishing the truth about past human rights violations have been excluded from our data. These include truth commissions or commissions of inquiry reports undertaken by non‐governmental organizations (Brazil, 1985), armed resistance groups (African National Congress, 1992 and 1993), special prosecutors (Ethiopia, 1992; Mexico 2002), and commissions that have a mandate limited to a single human rights violation (Côte d'Ivoire, 2000; Peru, 1983).

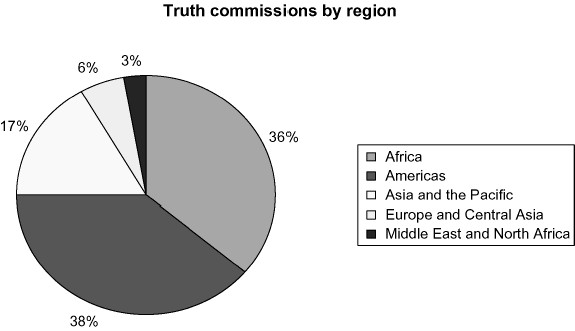

Our data also shows that truth commissions are regionally concentrated. As figure

12.2

illustrates, truth commissions are more prevalent in Africa and the Americas than in other regions, making up 36 percent and 38 percent of the total respectively. When combined, Africa and the Americas comprise 74 percent of the cumulative total number of truth commissions, whereas 17 percent are found within Asia and the Pacific, followed by only 6 percent in Europe and Central Asia, and 3 percent for the Middle East and North Africa.

When analyzed by region, there seems to be a similar upward trend across time, as illustrated in figure

12.1

, although the steepness of the upward slope varies by regional grouping. Once a region inaugurates its first truth commission, the number of truth commissions within that region seems to increase each decade. For example, the first truth commission in the Americas region was inaugurated in 1982, followed by an additional two truth commissions during the 1980s. The number of new truth commissions established in the Americas during the 1990s increased to five and already by 2004, only four years into the new decade, five new truth commissions have been established. This upward trend by decade also holds true for Africa, yet it remains to be seen whether or not the trend will hold for both Asia and the Pacific, and Europe and Central Asia as well. Given the overall trend of a justice cascade we anticipate that the pattern will remain consistent.

The data also illustrates that multiple transitional justice mechanisms are frequently used in a single case. In at least eleven of the countries we identified, both truth commissions and domestic trials were implemented.

[19]

Interestingly, most of these countries were found within the regions of Africa and the Americas and in most cases, truth commissions preceded trials. Thus, it simply does not hold true that countries must choose between trials or truth during democratic transition, although they may indeed choose to do so.

A modern cascade of criminal justice trials is similarly supported by our data. Without an existing comprehensive set of trial data to build upon, we identified our domestic, foreign, international, and hybrid

trials through human rights reports, United Nations documents and Security Council Resolutions, government news services, and information gathered by non‐governmental organizations.

[20]

Domestic trials

are those conducted in a single country for human rights abuses committed in

that

country.

Foreign trials

are those conducted in a single country for human rights abuses committed in

another

country.

[21]

International trials

involve international trials for individual criminal responsibility for human rights violations, such as the international ad hoc tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.

Hybrid trials

are third‐generation criminal bodies defined by their mixed character of containing a combination of international and national features, typically both in terms of staff as well as compounded international and national substantive and procedural law.