Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (58 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

Atlanta, Georgia 30346

REX USA LTD.

Please pass this on to anyone you feel might help make this little boy’s wish come true. [The leaflet is framed by tiny outlines of a child, and at the bottom of the sheet is printed “Thanks, K. Lee,” followed by a hand-drawn heart.]

C

lipped from a school newsletter, date and place unknown:

Attention Students:

Craig Shirgold is a 14 year old boy who has a brain tumor and has no chance of getting well. His last wish is to receive 1 million letters or greeting cards. This is your chance to grant a very important wish. It won’t take up too much of your time to write a few words.

Thanks a bunch!

[signed by two students]

Send to:

Craig Shirgold [followed by the Atlanta address in the above example] PS: Please tell everyone you know (including adults).

True? How could it be, with all those variations in age, disease, and addresses? I have left off specific sources so as not to embarrass the many people who have sent cards to Craig and circulated appeals for more cards. The above items are just a tiny sample from my ten-inch thick file of letters, E-mails, faxes, leaflets, and clippings documenting the Craig Shergold story. Or is it the Craig “Sherhold,” “Shargold,” or “Shirgold” story? And does he live on “Shelby,” “Sherlby,” “Selby,” or “South Selby Rd.” at number 26, 35, 36, 37, 38, 56, or 90? Is it “Surrey,” “Surry,” or “Surreny” and is the town “Carshalton,” “Charshalton,” “Carshaulton,” “Carshelton,” “Carshaltonn,” or even “Cahchalton,” England? The English postal codes listed also vary greatly. One version of the address even has him living in “Surry, British Columbia” in Canada, and then there’s that reference to Keene, New Hampshire. While some letters simply ask for cards or letters to be sent via an agency in Atlanta, Georgia, other letters claim that Craig himself lives in Atlanta. There’s also some variation on the address in Georgia, whether “Perimeter” or “Parameter” Avenue (or “Center”) and whether at number 32, 3200, or 321. So what’s the truth behind it all?

Craig Shergold’s supposed appeal for postcards, greeting cards, get-well cards, or business cards is a case of life imitating legend. What started as a fictional, but heartwarming, story about bringing happiness to a sick child turned into a nightmare when the flood of mail became overwhelming. Craig’s card collection eventually reached 33 million pieces, as reported in the December 24, 1990, issue of

Time

magazine, and his family has been trying for months to shut off the flow.

The saga began in 1982 when a mythical child known as “Little Buddy” was rumored to be pursuing a nonexistent record. Supposedly, this leukemia patient in Paisley, Scotland, wanted to break the record for number of postcards received as listed in the

Guinness Book of World Records.

There was no such record, yet millions of cards flooded in from well-wishers around the world, swamping the Paisley post office. There was no “Little Buddy” to whom the mail could be delivered.

The appeal circulated by word of mouth, mail, CB radio, and in the press. Then, in 1988, attention shifted to Mario Morby, a young English cancer patient. Mario announced that he wanted to beat the record he had heard about, and hordes of people sent him cards, either directly or through foundations that adopted his cause.

Mario’s name and his record of 1,000,265 postcards appeared in the 1989 Guinness book under the category “Collections.” But the flood of cards kept coming, and computer networks began to publicize the appeal. The postcards kept on arriving in ever-increasing numbers, much to the distress of everyone who had to deal with them. Before this stage of the card appeal slacked off, a rumor surfaced that Mario had died when a huge pile of mail sacks fell on him. Even the 1991

Old Farmer’s Almanac

printed this story.

Enter Craig Shergold of Carshalton, England, then a seven-year-old cancer patient, who in September 1989 set out to beat Mario’s postcard record. People enthusiastically shifted their efforts to Craig, and by November he had received over 1.5 million cards, a new record certified by Guinness.

Besides mail and computerized circulation of Craig’s appeal, a chain letter began to be faxed through business channels, each letter asking recipients to forward ten more copies. Craig’s surname, address, illness, and collecting goal all varied in these letters, but they quite consistently described him as seven years old and dying. In the United States some companies set up collection boxes in which employees were invited to leave cards to be sent to Craig, and at least one store printed the Craig appeal on its cash-register receipts in 1990.

Thanks to American billionaire John W. Kluge, in March 1991 Craig was brought to the University of Virginia medical center and operated on to remove a benign brain tumor. The June 10, 1991, issue of

People

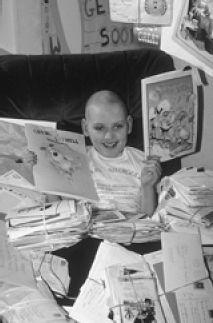

magazine spread the good news with a picture of a smiling Craig surrounded by sacks of unopened mail.

At that point his family wanted Craig simply to recover, live a normal life, and stop receiving massive card collections from well-meaning but misinformed people. The cards did lift Craig’s spirits, and there was another good side to the story: Kluge had heard about Craig and was moved to aid him when he received an appeal to help Craig get into the record book.

Among the scores of articles discussing and debunking the Craig Shergold card appeal are these: John Pekkanen, “The Boy and the Billionaire,”

Reader’s Digest,

March 1991; Charisse Jones, “A Dream Comes True and Comes True…,”

New York Times,

September 1, 1993; and the Phoenix-based Make-A-Wish Foundation Web site at http://www.wish.org/wish/craig.html.

“Green Stamps”

F

rom Ohio, 1988:

This story was told to me by a friend several years ago; the incident supposedly happened to her aunt.

A woman went for her annual gynecological exam, and she was extremely nervous, since it was a new doctor whom she had never been examined by before. As usual, she was instructed to go to the bathroom and provide a urine sample.

However, there was no toilet paper in the dispenser, so she reached into her purse and pulled out a tissue to use. Once she was undressed in the examining room the doctor entered and began his exam. When the woman was lying back with her feet in the stirrups the doctor pulled off a couple of S&H Green Stamps that had apparently been stuck to the tissue she used to wipe with, and he held them up and asked, “Excuse me, do you save these?”

This can’t possibly be true…can it?

P

ublished in 1983:

Giving Away Green Stamps

Dr. Burrand tells the following experience. “I had a lady come in for her annual physical examination.

My nurse had her remove all her clothes and get up on the examination table.

Almost at once she asked to be excused to go to the toilet. Unfortunately the paper holder was empty and instead of calling the nurse for a new roll she removed some tissues from her purse and used them.”

“The patient returned to the examining room and got back on the table, then called the nurse who called me,” said Dr. Burrand. The nurse kept the patient draped with the sheet but had her put her feet up in the stirrups for a vaginal examination. When I lifted the sheet to examine the patient, I was amazed and then amused to see a block of green trading stamps stuck to her butt. Apparently when she took the kleenex tissues from her purse, some green stamps clung to the tissues and were transferred to the patient’s skin without her knowledge,” said Dr. Burrand.

“Well, Mrs. Patient,” I said, “I know many people have a gimmick for various items for sale, but I don’t know what you’re using green stamps as a gimmick for, as I don’t know what you’re selling!” laughed the doctor.

P

ublished in 1988:

And double coupons, too?

A patient told me recently about her trip to the gynecologist for a routine Pap smear. Sent to the lavatory to provide a urine sample, she found no tissue, so she dug around in her purse and came up with a Kleenex. Later, during the exam, her doctor remarked, “Well, I’ve been paid a lot of unusual ways, but this is the first time anyone’s offered Green Stamps.” The stamps, it seems, had been stuck to the Kleenex.

—Lee A. Fischer, M.D.

A

letter from Montana, 1985:

I first heard the Green Stamps story in 1977 or 1978. It was told by a nursing supervisor of a hospital in Champaign, Illinois, who claimed it actually happened to her aunt. I loved the story when I first heard it, and I repeated it to everyone I knew.

About six months later, the same nursing supervisor and I were having lunch with several other people from the nursing office. The nursing supervisor told the Green Stamp story again, but one woman said, very matter of factly, “That story is not true.”

The nursing supervisor assured her that it was true, that it had really happened to her aunt. But the other woman insisted that she had heard the same story in Milwaukee some years before. The lunch party broke up with the nursing supervisor firm in the conviction that it had indeed happened to her aunt. The other woman told me later that she was furious with the nursing supervisor because she had so wanted to believe that the story she heard in Milwaukee was true. When she heard the tale repeated, she knew in an instant that the tale was apocryphal.

The first example above came to me from a reader of my newspaper column, then published in the

Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch,

who signed the letter only “J.W.” Of the 34 items in my Green Stamp file, most are like this version—vague as to place or date and attributed to a FOAF. Specifically, 28 of my filed versions refer only to a FOAF, and they come from all across the United States: from New York to California, New Mexico to Michigan, and Maryland to Texas. Two versions mention “Blue Chip” stamps, and one an Elvis postage stamp; I also have one version from London in which a postage stamp is mentioned. So far, then, the Green Stamp story would appear to be a typical urban legend, but what about these two published versions above, one of which purports to be told directly by the examining physician? The first of these (punctuated exactly as in the original) comes from a small self-published booklet entitled

Medical Mini-Shockers

by Stanley H. Macht, a retired radiologist in Hagerstown, Maryland. Dr. Macht says in his foreword, “These stories are true. They were reported by my colleagues.” The second published example comes from the trade magazine

Medical Economics

for October 17, 1988. When I wrote to the editor inquiring about the source, I learned that “the story was simply submitted as an anecdote—a humorous filler. We ask doctors to send us these ‘amazing, amusing, embarrassing’ little experiences, and we publish some of them.” Evidently the story is well known among medical personnel, as the last quoted example above suggests; it came in a letter from Anthony Wellever of Helena, Montana. While neither of the two published versions offers an airtight proof of the incident’s truth, I published two detailed accounts that claim to be first-person in

The Mexican Pet.

One was from a woman named Donna Cellar, who described exactly this incident as having happened to her, in the fall of 1963 in Dallas, Texas, and the other was from a woman whom I know very well who looked me straight in the eye and said the incident absolutely had happened to

her

in the late 1950s! This publication led to a number of further reports being sent to me, one of which was dated in the 1950s, and the others in the early 1960s. A typical example: “I heard the Green Stamp story in Glenview, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, from a woman named Ann Cole that I worked with from December 1, 1962 until May 31, 1963, that is, some time before your Mrs. Celler’s experience of Fall, 1963.” Another: “I heard the Green Stamp story told as current news from two friends at Charlie Taylor’s drug store in Perryton, Texas, in the summer of 1962. It happened to a former high school beauty queen whose maiden name was…” (Well, perhaps it’s best I do not quote the name). Frankly, at this point, I am not certain whether the Green Stamp story is an actual repeated experience, a mere legend that some women have adopted as “their own story,” or, perhaps, even a gynecologist’s prank. A final note: The 1990s version of the story circulating orally and on the Internet describes a woman who uses a “feminine hygiene deodorant” from a spray can just before her appointment for a physical exam. But she gets hold of a can of spray-on glitter instead, without noticing her mistake. The doctor comments something like, “Well, aren’t we fancy today.” Now that one has to be true, right?