Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (24 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

April 7, 1991

An Omaha woman trying on a fur coat at a local store is supposedly bitten by a poisonous snake. It seems, the tale goes, that the coat had been imported after a snake had laid eggs in the fur. The eggs hatched, and the coat became infested with young snakes…. The story is bunk, bosh, hot air, hooey and baloney.

September 17, 1994

Brick Township [New Jersey]: Police and the management at a local clothing store say a rumor making the rounds about a female customer being bitten by a snake is unfounded.

“We’ve been getting calls about this every day, but it’s nonsense,” Georgine Wilson, assistant manager of the Burlington Coat Factory store on Brick Boulevard, said yesterday. “I have no idea how this got started.”

According to the rumor, an elderly woman shopping at the store shortly before Labor Day reached into a coat and was bitten. When workers examined the coat, which purportedly came from Mexico, they found a snake in the lining.

A spokesman for the township police department said they had checked out the report and determined it to be unfounded.

“If that had happened, one of my managers would have told me about it, and I haven’t heard anything. Maybe it was a competitor jealous about how well we’re doing here, I don’t know,” Wilson said. “But you know a lawyer would have contacted us by now if it were true.”

From, respectively,

Weekly World News,

the

Springfield State Journal-Register,

the

Omaha Herald,

and the

Asbury Park Press.

Typically, the tabloid press furnishes the characters in the traditional legend with names and ages, making the item sound more like legitimate news. I was dead wrong in my 1981 book

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

in suggesting that this extremely popular legend of the late 1960s had mostly faded away by 1970; in fact, it has never stopped circulating, right up to the present. Often the alleged incident is said to have happened in a discount store: the Kmart chain was mentioned so often in the 1980s that the company maintained at its Troy, Michigan, headquarters a “snake file” containing hundreds of inquiries. Often the contaminated item is a blanket, sometimes an electric blanket; in these versions, the woman feels a prick and assumes it is a loose wire. She plugs in the blanket anyway, and the warmth causes snake eggs to hatch. Invariably, if an origin is mentioned, the snake is said to have come in on imported goods. This suggested to some during the late 1960s that perhaps the snakebite symbolized an unconscous national guilt complex about the U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. Certainly some distrust of foreign and bargain goods, as well as fear of snakes, is reflected in the legend. Other urban legends about snakes are included in Chapter 17.

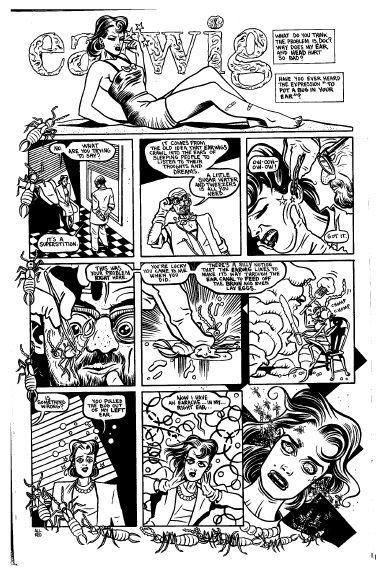

“A Bug in the Ear”

EARWIG ALERT

The Department of Health has brought to our attention the growing infestation of earwigs in Northern Illinois. The earwig is a small insect with forceps-like antennae, short forewings, many-jointed feelers, and pincer-like “beaks” at the end of the tail. Because of the mild days in January, the reproductive instincts of these insidious carnivores were triggered. Unfortunately, many of our children who were out in that relatively warm January weather, playing on the grass, may presently be host to this ravenous parasite.

These insects attach themselves to hair, clothes, and/or skin, and under the cover of darkness wend their way to the ear canal, burrowing then through the middle and inner ear and on into the brain. Upon reaching the brain, the earwig first severs the cranial nerves, which serves as both a blessing and a curse to the victim. Whereas the victim suffers no pain hereafter, neither is he or she immediately aware of the progressive degeneration of cerebral tissue, although it is often suspected by acquaintances. Both female and male earwigs require a human host in order to reproduce the species.

During the course of several days, the female earwig carves a catacomb-like network of tunnels through the temporal and frontal lobes of the brain, implanting numerous eggs in the soft, moist recesses of brain tissue. The female emerges in the sinus cavity, where, having deposited her eggs, she expires. She often is passed out of the body as a dark mass when the victim unexpectedly sneezes. The eggs of the female earwig begin to hatch after three or four days of incubation. These hatchlings, which are sometimes called “wiglets” or “letties” for short, or “lettes” for shorter, will hereafter be referred to as larvalettes. Immediately after emerging from their pupal sacs, each larvalette burrows backwards, using its pincer-like tail to shred brain tissue, passing the torn flesh to the mouth with its many-jointed feelers, whereupon it is ingested. This ability to both burrow and feed simultaneously makes it, pound for pound, an eating machine superior to even the Great White Shark.

If a male earwig enters the brain, mental debilitation will also result, but to a lesser degree. The male earwig enters the temporal lobe and moves directly to the posterior scleral membrane (the back of the eye), penetrating the sclera, choroid, and retina, finally entering the vitreous body of the eye. From there the earwig works its way to the aqueous humor between the lens and the corneal membrane. Thereafter, the male earwig leaves the body through the opposite ear; hence the phrase characterizing one who cannot process verbal information: “It goes in one ear and out the other!” Although mental debilitation and sometimes myopia result from the presence of the male earwig, the greatest danger has been found to be the trauma resulting in shock, should the victim awaken while the earwig is present in the aqueous humor. In this case, if the victim should open his or her eyes, an image of this hideous, pulsating parasite, magnified one hundred times, will appear. Treatment is usually effective only on larvalettes as once the adult earwig is beyond the middle ear, removal is usually impossible without a frontal lobotomy, which in almost 50% of the cases causes some personality changes. Larvalettes, which pose the greatest threat anyway, can be removed through a technical process in which the suspected victim is administered heavy doses of vitamins with iron. Immediately upon hatching, larvalettes begin eating. As the larvalettes ingest brain tissue, laden with vitamin-induced iron, they are susceptible to removal through the entry point created by the mother, by the application of a strong electromagnetic force (usually a forty pound pull magnet is sufficient, although a ten pound pull magnet applied four times should also be effective). If the victim is wearing braces or has a steel plate in his/her head, an orthodontist or neurosurgeon should be contacted for particulars on the safe removal of the larvalettes.

© 1999 Mike Allred

The most effective preventative measure yet developed requires the careful positioning of a small ball of cotton, which has been soaked for several minutes in blackstrap molasses, in the middle ear whenever one might be exposed to an infested area. In a household where a member has already been stricken by this dread carnivore, all other family members should follow the preventative measures described above before going to bed at night.

NOTE: Nurses checking for earwigs should wear rubber gloves and be sure not to inhale deeply near the ear canal as these insects could be transmitted nasally!!

An anonymous, undated, photocopied sheet sent to me in 1990 by Joyce deVries Kehoe of Seattle. This elaborate joke-memo—which I have shortened in quoting it—must have been composed by someone familiar with earwig folklore, plus having a wild sense of humor and some medical knowledge. The vague references to “Department of Health” and to an actual location are typical of photocopied bogus warnings (see Chapter 20). Earwigs get their names, as any good dictionary will tell you, from the mistaken idea that they particularly attempt to invade the human ear. Earwigs do occasionally get into ears, as numerous readers—some in the medical professions—have informed me after I published accounts of earwig lore. But these creatures, which are neither carnivores nor parasites, despite their name, are no more likely to enter a person’s ear than are ants, bees, cockroaches, centipedes, spiders, or any other small creepy crawly bugs. The typical earwig horror tales are that earwigs burrow into the brain and hollow out the head, or that earwigs can eat their way into one ear and come out the other, or that female earwigs lay their eggs in the brain while burrowing through. This memo expands on such themes, and caps them with ludicrous suggestions for treatment and prevention. Ironically, just as the very name “earwig” is derived from the notion that they frequently enter people’s ears, the folk beliefs probably continue to circulate largely because of the insect’s suggestive name.

“Spiders in the Hairdo”

W

hen I was in high school, the big thing was for girls to tease their hair. Now this looked nice on a lot of kids, but some girls carried it to extremes. They had these huge, bouffant hairdos, and they sprayed them really stiff with as much hair spray as they could get on. We used to wonder if some of these girls ever bothered to wash their hair so they could get all that sticky stuff out. One day we heard about this girl who went to a high school in Evansville who had just died because of teased hair. I think some of the teachers were trying to scare us into not teasing our hair anymore. Anyway, this Evansville girl had had one of these bushy teased hairstyles, and she’d kept lots of spray on it. They said she hadn’t washed her hair for three months. One day while she was sitting in class, she just keeled over, and when the teacher went to check on her, she saw blood trickling down her face. When they got her to the hospital, they found that a nest of black widow spiders had made a home in her hair and had finally eaten into her scalp.

Text number 289 in Ronald L. Baker's 1982 book

Hoosier Folk Legends,

as told in 1969 by a young woman from Princeton, Indiana. The next three legends in the same source, all from 1968 or ’69, describe hairdos similarly infested with cockroaches, ants, or maggots. This legend dates at least from the 1950s, when beehive hairdos became popular; the story lingers on now both in the memories of people who were students in those days or in legends about ethnic minorities, foreigners, or eccentrics of some kind. For example, one hears of “hippies” with insects in their long hair, or that the “dreadlocks” of reggae fans and musicians become infested with maggots. A possible prototype for the modern legend is an account in a thirteenth-century English collection of moral fables in which the Devil in the form of a spider attaches himself to the hair of a woman who is habitually late for Mass because she spends too much time arranging her coiffure.

“The Spider Bite”

A

twenty-year-old woman goes to Florida on vacation. She had a small sore on her face when she left and when she returned it kept getting bigger. When it became the size of a quarter, she went to a doctor who told her it was a boil and she would have to wait it out. Time passes, the bump grows, and is becoming very painful. She goes back to doctor who tells her that he will have to lance it but that he doesn’t have time in his schedule that day and that she should return the next day. During the night the pain becomes so intense that the woman wakes up screaming. The facial contortions from the scream make the boil break and out come all these spiders and pus. When the woman realizes what has been on her face, she has a heart attack.

I

was told this tale in 1980. The victim was a female relative (I believe an aunt) of a female colleague of my then girlfriend. The unfortunate woman was bitten by an insect while on holiday in Spain. The resulting lump failed to clear up with medical treatment on her return. Eventually it spawned a brood of small spiders and the woman needed psychiatric treatment to recover from the shock.

M

y daughter came home and related a story her friend had told her. I don’t believe it, but she does, because she says her friend wouldn’t lie. Here it is.

The friend’s sister-in-law noticed a very deep pimple developing on her cheek. After two weeks it finally came to a head, and when she popped it, tiny spiders ran out onto her face. She screamed and fainted. It seems a spider had laid its eggs under her skin two weeks earlier while she had been camping and had been sleeping out on the ground.

Please tell me it’s not true.

The first example is from a letter from Donna Schleicher of Madison, Wisconsin, responding to my article in

Psychology Today

(June 1980). The second is from a 1983 letter from Philip Tanner of Reading, England. The third version was sent by Christine Ackerson of West Valley City, Utah, in 1992. “The Spider Bite” was first noted in northern Europe—England, Scandinavia, Germany, etc.—in 1980, with the bite always occurring on or near the face during a time when the victim is vacationing in the south—Spain, Italy, or Africa. In many versions, on both sides of the Atlantic, the boil bursts and the spiders emerge while the victim—always a woman—is showering or taking a tub bath. Similar horror legends describe ants, cockroaches, maggots, etc., infesting a person’s sinus cavities or the flesh underneath a plaster cast. In most instances, the sufferer is said to have scratched the infested part of her body open with fingernails, a knife, fork, or rock, until the skin is broken and some of the critters come running out. See also the earwig alert above.