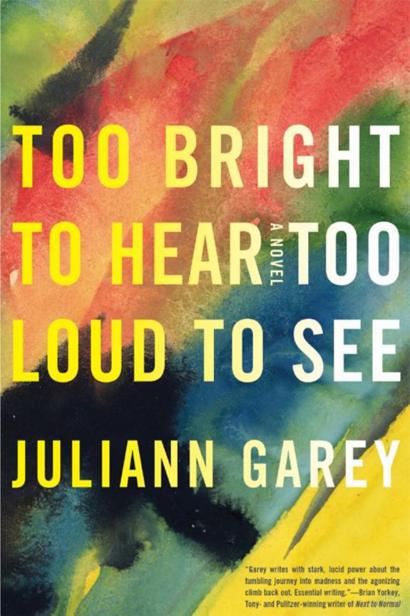

Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See

Read Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See Online

Authors: Juliann Garey

Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See

Garey, Juliann

Random House Inc Clients (2012)

A studio executive leaves his family and travels the world giving free reign to the bipolar disorder he's been forced to hide for 20 years.

In her

tour-de-force

first novel, Juliann Garey takes us inside the restless mind, ravaged heart, and anguished soul of Greyson Todd, a successful Hollywood studio executive who leaves his wife and young daughter and for a decade travels the world giving free reign to the bipolar disorder he's been forced to keep hidden for almost 20 years. The novel intricately weaves together three timelines: the story of Greyson's travels (Rome, Israel, Santiago, Thailand, Uganda); the progressive unraveling of his own father seen through Greyson's eyes as a child; and the intimacies and estrangements of his marriage. The entire narrative unfolds in the time it takes him to undergo twelve 30-second electroshock treatments in a New York psychiatric ward. This is a literary page-turner of the first order, and a brilliant inside look at mental illness.

Copyright © 2012 by Juliann Garey

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Epigraph is from the original C.K. Scott Moncrieff translation of

Swann’s Way

This book is a work of fiction. References to real people, events, establishments, organizations, or locales are intended only to provide a sense of authenticity, and are used ficticiously. All other characters, and all incidents and dialogue, are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Garey, Juliann.

Too bright to hear too loud to see / Juliann Garey.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-61695-130-6

1. Manic-depressive illness—Fiction. 2. Self-realization—Fiction. 3. Fathers and sons—Fiction. 4. Marriage—Fiction. 5. Psychological fiction.

I. Title.

PS3607.A744T66 2012

813′.6—dc23

2012026028

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

v3.1

For Michael, Gabriel and Emma

And, as ever

In memory of my father

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Fifth

Sixth

Seventh

Eighth

Ninth

Tenth

Eleventh

Twelfth

Aftershocks

Acknowledgments

We are able to find everything in our memory, which is like a dispensary or chemical laboratory in which chance steers our hand sometimes to a soothing drug and sometimes to a dangerous poison.

—Marcel Proust,

In Search of Lost Time

FIRST

Willing suspension of disbelief. That’s what they call it in the movies. Like the story about how each procedure will be over in less than a minute. And how you won’t feel a thing. How you may be foggy for a while, but in the end you’ll be better. You’ll be whole

.

I want that. So I suspend my disbelief. I let them hook me up. Willingly. And then they give me something. And when I close my eyes, I am neither asleep nor awake but rather suspended in the dark, somewhere between the two. Willingly suspended. Watching. I feel my eyelids being taped shut and hear the gentle hum of the electricity. I have no choice but to give in and let the story tell itself

.

Los Angeles 1984

. California is a no-fault state. Nothing is ever anyone’s fault. It just is. Day after day. Until it kills you.

Automatic sprinkler clicks on at dusk.

SssstChchchSssstChchch

. Flattens oak leaves—yellowy, brown-veined—against stiff green lawn.

It is a warm September night when I leave my wife and eight-year-old daughter. I tell my wife I’m going out to the backyard to clean up the dog shit. It’s the one chore I’ve never really minded. A couple of times a week, I use a long-handled yellow plastic pooper-scooper that came with an accessory—a narrow rake designed to help roll the turds into the scooper. I make my way systematically across the lawn in a zigzag pattern. The dogs, a couple of beautiful overbred Irish setters who suffer from occasional bouts of mange, enthusiastically follow, sniffing as if hot on the trail of something other than their own crap. When the scooper gets full, I dump it into one of the black Rubbermaid garbage cans I keep in the garage. And when I’m done, I spray down my equipment with a fierce stream from the gun-like attachment I screw on to the green hose I use to top off the swimming pool. By the time I’m finished, the scooper is clean enough to eat off of.

“Jesus Christ, Greyson,” my wife, Ellen, yells out the kitchen window, “it would be a whole lot easier if you’d do that during the day when you could actually see the shit.” This is something she yells out the kitchen window almost ritually. But I always do it at night. I like the challenge.

Ellen accuses me of being antisocial. It’s not true. My work as a studio executive demands a tremendous amount of social intercourse, the appearance of impeccable interpersonal skills, the ability to read the room better and faster than anyone, to negotiate every situation graciously and ruthlessly to my advantage.

I can hardly breathe.

I use the front door less and less these days. Want the ritual welcoming of the hunter/breadwinner less and less. Instead, most nights I let myself in through the little gate that leads to the backyard. I desperately need a solitary hour to catch myself by the scruff of the neck and stuff myself back inside that hollow glad-handing shell.

He

is all style and glitter and fast-talking charm. I cannot stand to be inside him when he does it. Now, the best I can do is stand next to him and watch.

I used to love my job. Didn’t even mind the commute. After a cool rain or a good stiff breeze, the sickly yellow mattress of smog that hangs cozily over the Valley dissolves briefly. You can inhale without tasting the cancer in the air. That used to be enough for me. I have made the studio a lot of money over the years. My personal compensation—bonuses, stock options, gross points, profit-sharing—has been more than fair. I can’t remember when exactly it was that the phone calls, the meetings, the glad-handing that once provided such a rush, ceased to be a source of pleasure. But through a combination of experience, luck, fear, and an excellent secretary, I have held on.

It is difficult to find oneself after pretending all day. Eventually you are nothing more than a suit, a car, and a business card. So at night I go straight to the backyard, strip off my Armani chain mail, and dive naked into the cool turquoise pool. The shock of the cold water reminds me—

my

body,

my

skin.

Without toweling off I put on a terry cloth robe and slip through the sliding glass doors into my study at the furthest end of the house. I want nothing more than to sit alone looking out through the glass doors, watching leaves from the big, twisted maple tree in the backyard fall into the swimming pool. The branches of the tree have grown so large that the shallow end of the pool is always in the shade. No matter how high I turn up the heater, it’s still chilly to swim there. But I refuse to let Ellen have the tree people come to cut it back. I need to see the leaves fall.

All day, every day, there is so much noise. Everything seems so much louder than it used to. I just want to be left alone. My wife is not quiet about what she considers to be my increasingly reclusive tendencies. She wants more. I don’t have what she wants.

So I’ve paid off the mortgage, signed a quitclaim deed putting the house and a trust in her name, and I’ve packed a small suitcase and locked it in the trunk of my Mercedes. Nameless, easily accessible offshore accounts have been established.

Work is something else. I don’t know where to begin. So I just leave it all—scripts half read, deals half done, foreign rights half sold. I want to apologize. Tell them we had a lot of good years. It’s not you, it’s me.

Truth is, though, the career of the average studio executive is slightly shorter than the lifespan of the average Medfly—those minuscule fruit flies being hunted by low-flying California Highway Patrol helicopters whose pilots spray insecticide over the Los Angeles basin at the height of rush hour. Best I could hope for at the end of my run is an indie-prod deal at the studio. A producer’s office from which nothing is ever produced. That’s if I’m lucky. I’ve seen better men than me leave my post with less. So, stay, go—the point is moot.

That last night—before dinner, before the dog shit, before I leave—I am sitting in my study watching the deadest of the leaves float on the surface of the pool and get sucked toward the filters at the shallow end. The pool man will be pissed off at the extra work. I am smiling at the thought when my daughter, Willa, walks in, small and blonde and long-legged. She has little circles of dirt ground into her kneecaps from playing on the black rubber under the jungle gym at school. She sits on my lap.

“I have a surprise for you,” she says in a singsong voice intended to create suspense. Her breath is sweet and new.

“Oh yeah, what’s that?”

“Ta-daa.” She dangles the thing so close to my face that I can’t see it. “It’s a key chain, see?”

It’s a heart cut out of cardboard and painted abstractly in the same primary colors that cling to her ragged fingernails and cuticles. Her school picture is stuck in the center. Elmer’s glue has oozed out from under it and dried in hard, gray blobs. There’s a hole punched in the top and a chain. It won’t hold more than one or two keys without ripping.

“It’s beautiful, thank you,” I say, trying to mean it.

She looks at me for a while. I force an unconvincing smile and she looks away. She slides off my lap and onto the rug. I don’t ask her what’s wrong. I’m afraid she might answer.

Some people shouldn’t be parents. I simply found out after the fact. I cannot tolerate the myriad responsibilities anymore—birthday parties and teacher conferences, soccer games and ballet recitals. And just as intolerable is the suffocating guilt of not attending those things. I cannot stand to disappoint. So better gone than absent. It is the only way to love her.

We look up when we hear Ellen talking to the dogs. She is walking across the Spanish tile in the kitchen and down the three steps to my study. She stands in the doorway and sighs heavily. She is barefoot and wears a pair of faded jeans with a hole in the right knee that gets bigger each time she washes them. She must have twenty pairs of jeans in her closet, yet she rarely wears any but these. Ellen gets attached to things—holds on to them even when they’re torn and damaged and past their prime.

“There you are,” she says, though she’s clearly not surprised. “I don’t know why we bother with the rest of the house.” She looks from me to Willa. “What’s wrong, Will?” Willa hugs her knees into her chest. “Did Daddy like his present?” She hugs her knees tighter, tucks her chin, and rolls backwards into a somersault.